Resilient engagement playbook: How Europe can navigate relations with a more confrontational Beijing

| This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

European states must ensure that engagement with Beijing enables EU–China co-existence while protecting the EU’s interests and values. It should support and complement, rather than undermine, a more assertive and coherent China policy and help avert crises that would be disruptive for Europe, says Grzegorz Stec.

Recent tensions with China are confounding EU states’ hopes for a more amicable approach from Beijing, especially after Donald Trump’s new US administration imposed stiff tariffs on China earlier this year. Now, Beijing is using its economic security toolbox even more aggressively – to the detriment of the European economy and potentially its developing defense industry, while Europe is considering how to respond.

For example, China’s licensing and restrictions recently made it harder for European companies to obtain rare earths needed for many advanced tech products. The Dutch government’s decision to take control of chipmaker Nexperia from its Chinese owner threatened the global operations of Europe’s automotive sector and caused a flurry of diplomatic activities aimed to prevent escalation and buy time for developing a sustainable solution. Navigating political relations is becoming more complex as shown by the postponement of German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul’s October trip to China over disagreements on the visit’s program and diplomatic tensions.

The geopolitical and geoeconomic frictions make engagement with China essential, but this engagement also entails risks and presents a challenging balancing act. French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer are expected to visit China over the next few months, raising the question of how governments can remain resilient in the face of tensions while engaging with China – and what tools work best.

Engagement with China is essential

European engagement with China must be focused on crisis management, damage control and facilitating co-existence when longer-term cooperation seems out of reach.

Keeping channels of communication open is essential for crisis management. The talks on rare-earths export controls, for example, helped to blunt the shock of China’s restrictions and manage Beijing’s reactions to Europe’s moves. Communications can also help manage and defuse escalations around specific incidents such as the alleged laser targeting of a German aircraft by a Chinese warship in the Red Sea, or deal with larger, global crises such as the Covid pandemic which required timely exchange of information.

China also remains a key actor in addressing global challenges such as climate change, regulating emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, reforming the international order or protecting global health. Even if it oftentimes is not a constructive partner for the EU, China plays an important role that impacts the EU’s fundamental interests on the international stage. Engagement can help to navigate that.

Although “engagement for engagement’s sake” has been justifiably criticized, sustained high-level exchanges remain one of the few channels to puncture the party state’s echo chamber, signal resolve and pursue deterrence, reduce misreadings of the EU’s positions and pose questions to Chinese partners. On top of that, leaders and officials cannot ignore that the future of industrial development and innovation dynamics will also be shaped in Beijing. Opportunities for “learning” and staying informed should encourage European leaders to continue to engage.

Cooperative agendas and their limits

Over the past six years, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and the UK pursued the most active high-profile engagement with China.

Among those actors over the last year:

- France developed the most joint statements with China, including on the “situation in the Middle East” (May 2024) with support for the two-state solutions and nuclear non-proliferation; on AI governance (May 2024) “based on the principle of AI for the common good”; and on combating climate change (March 2025) and the protection of oceans, biodiversity and the so-called “blue economy” (May 2024).

- The scope of Germany’s China engagement under the Merz administration is yet to be defined. It will follow the recently launched Dialogue and Cooperation Mechanism on Climate Change and Green Transition with its dedicated track on industrial decarbonization and a 2023-2026 action plan to “strengthen international development cooperation,” in particular in Africa.

- The UK has been reactivating frameworks such as the High-Level Economic and Financial Dialogue and Joint Commission on Trade and Economy and planned relaunch of the Joint Commission on Science, Technology and Innovation. London stands out in engagement on financial regulatory cooperation, asset management and green finance, e.g., through the UK-China Stock Connect.

More broadly, there are several ways member states have been trying to lock in China’s commitment for practical cooperation, including bilateral action plans to strengthen relationships (such as the 2024 – 2027 plans by Italy and Poland), sectoral action plans, topical agreements and memorandums of understanding (MoUs), or joint declarations.

However, even locked-in action plans or agreements with Beijing warrant caution and close monitoring. Italy’s experience with the MoU on participation in the Belt and Road Initiative shows the limits of broad, vaguely worded agreements. The underwhelming progress led Rome to halt the automatic renewal of the agreement in December 2023, cancelling Italy’s participation in the initiative.

But even technical, actionable agreements with China can underdeliver. For instance, while hailed as a major achievement, the 2021 EU-China Geographical Indications (GI) Agreement, a bilateral agreement protecting 100 EU and 100 Chinese agricultural products against imitations, is still facing problems. Implementation has lagged as China’s current legislative framework does not include sufficient provisions to bring dedicated GI cases to courts.

Resilient engagement with China: Safe, Smart, Selective

Limiting engagement would be self-defeating but so would pursuing it with only cooperation objectives in mind or without risk-mitigation measures. Europe’s approach also needs to address Beijing’s increasingly confrontational posturing. Engagement can be a cost-efficient way to stabilize relations and avoid the most disruptive fallout, as long as it does not prevent Europe from developing a more coordinated and assertive China policy.

In engaging with China, member states could draw on the following principles:

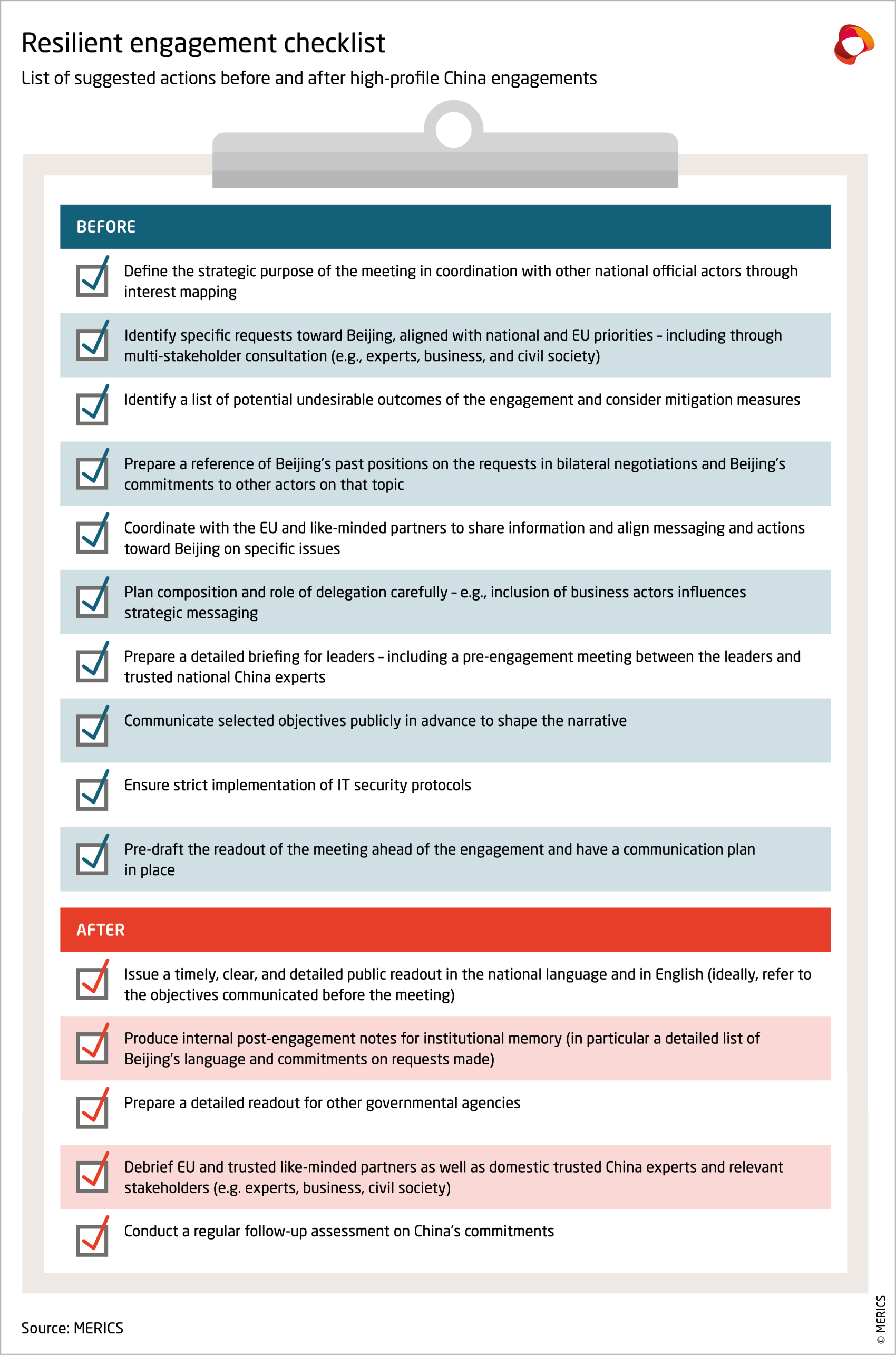

Safe: Risk-conscious and Well-communicated

- Conduct risk and cost assessments of the engagement, as Beijing has a track record of using diplomatic encounters to erode EU unity, to manipulate narratives, or to make the countries concerned delay assertive actions towards China until after the engagement to avoid diplomatic tensions. Put mitigation measures in place and ensure there is little or no impact on planned national resilience-building actions.

- Communicate the objective ahead of and right after the engagement so Beijing cannot gain control of the narrative, which can push other actors to misinterpret European intentions. Align messaging with the established EU line to avoid eroding European unity and credibility.

Smart: Purposeful and Coordinated

- Define a clear strategic purpose for engagement that serves long-term EU and national interests, not short-term goals. The purpose does not need to be cooperation or a collaborative agreement. Communication objectives such as deterring unwanted behaviors, sharing information or testing China’s reactions are also viable. Clearly defined national strategic interests toward China should be the basis, ideally set out in a document that is regularly reassessed and updated.

- Coordinate across government agencies and with EU and trusted like-minded partners for information-sharing and alignment of actions. Delivering similar messages or pursuing several actions toward China simultaneously can deter or at least delay Beijing’s decision to take undesirable actions.

- Engage a wider range of stakeholders to inform engagement beyond government-to-government relations. Business, academia, civil society and others are autonomous actors shaping ties with China in areas like trade, standards and scientific cooperation. Ensure their insights inform the government’s agenda and in turn provide them with clearly articulated recommendations to limit uncertainty.

Selective: Verifiable and Conditional

- Tie any potential cooperation to concrete, time-bound, independently verifiable benchmarks to make it harder for China to avoid implementation or use diplomatic stalling. If possible, aim for Beijing to publicly communicate its commitments so that the pressure of international public opinion can help regulate Beijing’s behavior, even if only to a limited extent.

- Use modular designs in cooperation agreements with snap-back clauses so cooperation can be scaled or suspended if Beijing underdelivers. Explicit milestones and timelines may advance or terminate projects and create transactional interlinkage between progress on the EU’s and China’s priorities.