5. Delivering Global Public Goods

By Nis Grünberg and Thomas des Garets Geddes

This is chapter 5 of the MERICS Paper on China "Towards Principled Competition in Europe's China Policy: Drawing lessons from the Covid-19 crisis."

Key Findings

- The Covid-19 pandemic and the global climate crisis have put the spotlight on the need for global cooperation, with issues around China front and center.

- It is by no means a given that China will be “building back greener” after the crisis. Beijing is under massive pressure to restart the economy and commitments to climate and energy reforms are already taking a backseat.

- On climate, the EU will have to step up its game and engage China more forcefully to shape its behavior.

- The EU needs to make its support for Chinese initiatives like the AIIB and BRI conditional on binding commitments to the climate (and financial) sustainability of projects.

- On global health, the EU will find itself in a position of supporting and leveraging. Yet on China’s heavy-handed efforts to gain support for its Covid-19 response model, the EU should adopt a decisive resist and limit response.

- On the other hand, the EU should continue to actively engage and cooperate with China on targeted global health projects and research.

1. Crisis lessons: Power politics and contested responsibilities threaten global solutions

The Covid-19 pandemic and the global climate crisis have not only had a dramatic impact on millions of lives across the globe, they have also put the spotlight on critical national responsibilities and the need for global cooperation, with issues around China front and center in a way that matters fundamentally to Europe.

During the first months of the crisis, China’s role in delivering effective solutions was heavily contested on multiple fronts. Beijing’s role in the World Health Organization (WHO) was the main reason put forward by Washington pulling out of the organization. The supply of PPE from China split the world into grateful recipients and critics doubtful of its motives. In Europe, Beijing’s mask diplomacy and associated disinformation has, overall, damaged China’s image. And when the EU organized a global pledging conference in May 2020, both the US and China were missing in action.

For a short period, at the beginning of the pandemic, levels of air pollution in China and elsewhere dropped significantly, but going forward, climate cooperation might become another victim of the crisis. It is, for instance, by no means a given that China will be “building back greener”; quite the contrary – under massive pressure to restart the country’s economy, Beijing's commitments to climate and energy reforms are already taking a backseat.

The corona crisis is a strong reminder that the provision of Global Public Goods (GPGs), including on global health and climate, constitutes another arena in which great powers not only have to prove themselves. They also have to prove they can work together effectively with others, despite political differences. The EU, for example, has committed to delivering GPGs as “integrated rather than fragmented solutions” for global problems.1

To address such global challenges and shape global cooperation in accord with OECD principles and European interests, getting to grips with China is and will be central. The EU will increasingly find that China is ambitious in its own efforts to shape the provision of GPGs. As the largest emitter of CO2, Beijing needs to take on bigger responsibilities in global climate action. On questions of global health and climate, cooperation with China will, however, be hampered and frustrating given growing distrust in other arenas, shifting domestic priorities, global power politics and political differences.

Recognizing these constraints, the EU will have to pursue a two-pronged strategy vis-à-vis China on climate and global health: doubling-down on conditional cooperation to engage China and shape its behavior while competing in actually delivering these GPGs to create pressure for upward convergence.

2. China's trajectory: China acts on domestic priorities, global expectations and branding opportunities

China is still a relative newcomer to the provision of GPGs. Up until just a decade ago, it was rare to hear Chinese leaders discuss or promote China as a global GPG player. Yet in recent years China has moved from cautious defensive behavior to a much more proactive role. Today, Beijing claims to be a climate leader and is keen to promote and protect Chinese interests in climate negotiations. It has ramped up its role in the WHO and branded its “Health Silk Road” as an example of its participation in cooperative global responses to the crisis.2 There are three main drivers of this growing involvement in GPGs: (1) pressing domestic problems, (2) foreign pressure and expectations, and (3) opportunities to shape (perceptions of) China’s global role.

The first driver behind China’s growing role in participating in the provision of GPGs is China’s own domestic challenges. Climate change for example, is recognized by Beijing as a “huge challenge to the survival and development of the human race”.3 In the last decade, China has focused on moving away from fossil fuel, and ramped up environmental regulation. China has also become much more willing to participate in global climate and energy discussions, tapping into broader global discussions and networks on climate solutions, including advanced green tech useful for Chinas domestic development. Lastly, domestic climate action is claimed to be a contribution to GPGs, as well as to ‘greenwash’ party rule.

The second driver of China’s more active role in GPG provision is pressure and expectations from other countries. In particular, China has responded to changes in US GPG policy and behavior. Calls for China to be a more “responsible stakeholder” have had an impact: it is increasingly willing to adopt the language of “responsibility” and “global public goods” in its foreign policy,4 and its commitments as well as the cooperation with the US required for the Paris climate agreement signaled the possibility of real joint or aligned action in the face of global challenges.

A third and more challenging motivation for China’s growing involvement in GPGs is Beijing’s disposition to exploit strategic and image opportunities as they emerge. Since 2017 and during this crisis, Chinese leaders have been keen to point to diminished US support for global climate solutions and global health institutions, and to contrast this with Beijing’s own supposedly responsible role.

However, China’s narrative about GPG provision often takes awkward turns. On development issues and the BRI, China claims that its own unilateral policies and initiatives are already a type of GPG, and every Chinese overseas infrastructure loan is sold accordingly as a GPG contribution. During the corona crisis, China’s state propaganda went into overdrive to promote China’s image as a “responsible great power” (负责任大国),5 which made the discrepancies between these branding efforts and actual behavior even harder to reconcile for most western international onlookers.

Taken together, these three drivers put China on a challenging trajectory for Europe. While systemic differences should not matter that much, the crisis has shown that a lack of trust and transparency and putting propaganda over substance creates massive hurdles for actual cooperation in GPG provision. While both sides might align on the analysis and increasingly on ambitions, specific interests and priorities will diverge in practice.

3. Key issues: Balancing cooperation and competition in global public goods delivery

In the area of GPG provision, the EU has clearly stated positions and aspirations. It targets five key issue areas as matters of priority: environment, health, knowledge, peace and security, and governance. While the first two of these are broadly aligned with Chinese priorities, they also differ significantly in the detail. Moreover, EU emphasis on good governance as a GPG, which rests on support for liberal political and economic institutions and processes, is almost certainly at odds with China’s own GPG aspirations.

Issue 1 – Climate negotiations: Old wine in new bottles

On climate, Europe will rightly seek cooperation with China in two specific areas: climate negotiations and the promotion of a “green” BRI. On the Paris Agreement targets, China has moved from being a skeptical participant to the UN climate talks in 1992, to one of the most active voices. And under Xi Jinping, China has made much of its aims to promote “ecological civilization” at home and abroad.6 Even in the midst of the corona crisis, China, at the national level, has banned coal-related projects from receiving green finance, boosted clean electricity targets, and pushed regional power sector consolidation to reduce coal power overcapacity.

Yet such ambitions belie challenges and contradictions. China seems unlikely to move away quickly from coal power generation. In the first six months of 2020, China approved coal-fired powerplants with a total capacity of 48 GW for construction.7 And despite decommissioning old plants and consolidating regional power companies, eight months into 2020, coal power capacity has seen a net increase of 20 GW. The country’s response to the corona crisis will emphasize economic recovery and therefore downplay clean energy targets and environmental concerns. Efforts to forge a “green recovery” and implement an emissions trading system are likely to disappoint as they take a backseat to employment-generating policies, including in heavy industries.

Issue 2 - Green BRI: Under financial pressure

A “green BRI” is China’s official effort to promote its overseas infrastructure agenda as environmentally friendly. Especially since 2017, China has made a series of high-profile statements about the BRI, claiming it is part of a broader commitment to mitigating climate change and to promoting cleaner sources of energy.

Yet the green BRI agenda, too, is beset with contradictions. Well over half of BRI investments and financing have been devoted to energy projects, but many of those have been for polluting coal-fired power plants. In addition, Chinese firms have increasingly invested in or financed energy grid projects, many of which themselves transmit energy from fossil fuel sources. Given the economic impact of the corona crisis, China’s commitment to a more climate friendly BRI will therefore run up against the challenges of limited budgets, especially in poor and emerging markets.

Issue 3 – Global health regimes: A new BRI playing field

On global health, China used to keep a relatively low profile within the WHO, especially after it was criticized for covering up the 2003 SARS outbreak. Since 2017, however, China’s role has expanded, with financial contributions to the WHO having more than tripled to around 221 million USD for the 2020 - 2021 budgetary window.8 Controversies have arisen around China’s role in the WHO’s response to Covid-19 because of the way it stifled criticism about its own initially slow and opaque response to the virus’s outbreak in Wuhan. Its continued intransigence toward granting Taiwan observer status in the WHO’s World Health Assembly has further underscored worries that China’s political interests and values are at odds with the organization’s core global health mission.

In addition, China has used the pandemic to revitalize a little-known offshoot of the BRI, the Health Silk Road (HSR), as part of its contribution to global health solutions. First announced in 2015, the HSR built on the BRI framework to promote various Chinese health cooperation efforts, including for pandemic preparedness, aimed at improving public health in developing country regions, especially in Southeast Asia. China had long developed a global footprint in building hospitals and partnerships for medical knowledge transfer. However, with the outbreak of Covid-19, China emphasized its “mask diplomacy” and digital health applications as being also part of this initiative.9 The HSR and affiliated projects have received support within the WHO, an example of how China’s role in international health organizations can bolster its broader global health ambitions.

4. EU-China relations: Europe is in the lead, but getting China on board remains the ultimate test

The EU comes to GPG provision with much longer experience in OECD cooperation and is a leader on many of the standards, norms and multilateral institutions that are at its heart. The EU therefore has significant strengths when it comes to setting the GPG agenda even if the actual joint provision of GPGs remains difficult.

On climate as a GPG, the EU is one of the most important and influential actors. However, while sharing many overarching climate cooperation goals with China, the EU is limited in its leverage because of international and domestic Chinese realities. Without US pressure and participation in delivering on Paris commitments and broader climate change cooperation, China is more easily able to tone down more ambitious targets formulated in its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) of the Paris agreement.

On China’s promotion of a “green BRI”, the EU also faces contradictory Chinese behavior and has limited tools to leverage changes on China’s side. Even in the area of possible cooperation on climate-friendly energy, China’s procurement and subsidy policies make European participation in greener BRI projects difficult. The EU’s connectivity strategy has potential as a policy instrument to engage with China or provide support for EU firms to move toward more “sustainable” energy and other infrastructure development. However, the EU has yet to fund or move forward with this.

In the arena of global health, EU member states and Brussels are significant players. Germany and France (and, in the past, the UK) have laid out and acted on ambitious strategies with a global horizon. Excluding what EU member states give individually, EU institutions spent 1.2 billion USD on official development assistance to health in 2016, a large share of which was earmarked for multilateral institutions, including the WHO. In response to Covid-19, in contrast to China’s approach, the European Commission has pushed for a multilateral effort and helped raise 7.4 billion EUR at a donor conference in May for the development and distribution of vaccines against the virus .10 Moreover, through its own medical and pharmaceutical industries and research, EU countries are important providers of medical equipment and life-saving drugs.

5. Policy Priorities: Contingent engagement on climate change and global health

There is broad overlap in EU and Chinese interest to support the provision of GPGs in general. This stands in unfortunate contrast to policies of the current US administration which, under President Trump, is retreating from decades of leadership in this arena. The EU will want China to move in directions that progressive forces in its system, such as doctors, scientists, and environmentalists, have said it should move towards. This will often mean holding China to such commitments through a mixture of incentives and disincentives.

On climate, the EU will have to step up its own game and engage China more forcefully to shape its behavior. As the United States remains a key factor, pushing China to become greener will require deeper EU-US cooperation on climate in whatever way possible. Where China and the EU have existing partnerships and cooperation (e.g. the Paris agreement and EU-China strategic cooperation), the EU must double down and hold China to its own words. The EU must be better at “doing its homework” on China's domestic policies so that it can hold China accountable, for instance on its lofty “ecological civilization” ambitions. China’s 14th Five-year plan, setting out its national goals for 2021-2025, is probably the world’s most consequential policy framework affecting global efforts to tackle climate change.

EU engagement with China on trade, science and technology cooperation, investment and finance should also be made contingent on climate change discussions and policy. This will be challenging on both sides, and if the EU wants to build leverage on this matter, it must also enact stricter and more ambitious policies at home.

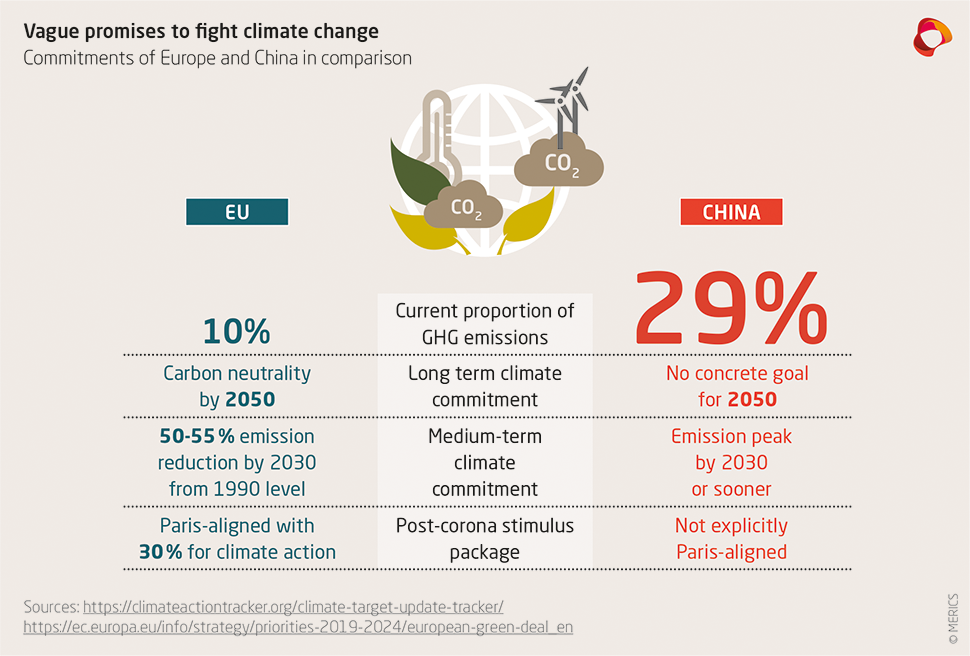

Only by leading by example can Europe sell its green ambitions abroad, including to China. The coming months offer a small window of opportunity for a more ambitious Europe-China climate partnership. To get there, NDC discussions should be prioritized, especially with regard to the long-term strategy for 2050 net zero. While the EU has committed to zero carbon by 2050, China has not stated any concrete long-term commitments. In order to achieve the Paris agreement’s targets, however, China must accelerate investment in zero-carbon electrification, also with the help of European technologies.

The EU should also make its support for both the AIIB and BRI directly conditional on binding commitments to the climate (and financial) sustainability of financed projects, with the goal of phasing out fossil and coal investments. The EU should enlist global partners for bolder standards regarding international energy projects and green finance. The connectivity strategy and its commitments to “sustainable” connectivity remains the single best framework for pushing China toward higher standards and supporting EU firms that abide by these, too.

On global health, the EU will likewise find itself in a position of supporting and leveraging, but also moving toward engaging and shaping China’s behavior. Yet on China’s “mask diplomacy” or its heavy-handed efforts to gain support for China’s Covid-19 response model, including through the WHO, the EU should adopt a more decisive resist and limit response.

With the United States’ declining influence in the WHO, it is EU member states that, together, should fill the void. They must act as a counterweight to Beijing when it attempts to re-shape the rules, norms and values that underlie global health governance institutions. The EU and its allies must ensure that the WHO remains an independent and objective organization — capable of asserting its authority and refusing political interference during international health crises. EU member states should therefore use their financial and diplomatic weight to push through much needed reforms within the UN agency. In particular, the EU should promote reform of the WHO’s funding system, emergency management mechanisms, and independent post-epidemic investigations. The EU should also aim to help Taiwan obtain observer status at the World Health Assembly.

China’s Health Silk Road presents the EU with multiple new policy challenges. On the one hand, the EU should unite with like-minded countries to push back against Beijing’s corona propaganda and disinformation campaigns. On the other hand, the EU should continue to actively engage and cooperate with China on targeted global health projects and research. When China makes widely publicized financial pledges towards global health, the EU should ensure that Beijing delivers on these promises and should call it out when it does not. In general, the EU should demand much more transparency when it comes to China’s bilateral health programs and encourage Beijing to funnel a greater share of its development assistance for health through multilateral organizations.

- Endnotes

-

1 | European Commission (2002). “EU Focus on Global Public Goods.” The EU at the WSSD, 2002. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/wssd/pdf/publicgoods.pdf. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

2 | Bayes, Tom (2020). “Mao called it snake oil – How China uses the Corona crisis to promote traditional medicine in Africa.” May 19. https://merics.org/en/analysis/mao-called-it-snake-oil-how-china-uses-corona-crisis-promote-traditional-medicine-africa. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

3 | Su, Wei (2015). “Enhanced Actions on climate change: China’s nationally determined contributions”. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/China%20First/China%27s%20First%20NDC%20Submission.pdf. Accessed: August 25, 2020.

4 | Global Times (2020). “China and Europe defend world pillars under US threat.” August 21. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1198796.shtml. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

5 | Jiefang Junbao 解放军报 (2020). “中国战“疫”展现负责任大国担当“ (China’s war on “epidemic” demonstrates it takes on its role as a responsible power). http://www.mod.gov.cn/jmsd/2020-04/13/content_4863510.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

6 | Hansen, Mette H., Li Hongtao and Rune Svarverud (2018). “Ecological civilization: Interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future” Global Environmental Change, 53: 195-203.

7 | Bloomberg News (2020). “China Seen Adding New Wave of Coal Plants After Lifting Curbs.” June 10. https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/china-seen-adding-new-wave-of-coal-plants-after-lifting-curbs-1.1448154. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

8 | WHO (2020). “Funding by contributor country page China”. August 31. https://open.who.int/2020-21/contributors/contributor?name=China. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

9 | Arcesati, Rebecca (2020). “The Digital Silk Road is a development issue.” April 28. https://merics.org/en/analysis/digital-silk-road-development-issue. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

10 | European Commission (2020). “Coronavirus Global Response: €7.4 billion raised for universal access to vaccines.” May 4. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_797. Accessed: August 31, 2020.

This is chapter 5 of the MERICS Paper on China "Towards Principled Competition in Europe's China Policy: Drawing lessons from the Covid-19 crisis." Continue with Chapter 6 "Engaging in effective geopolitical competition" or go back to the table of contents.