MERICS Global China Inc. Tracker

No. 1, März 2022

Focus Topic: The War in Ukraine and the Future of the BRI in Europe

The symbol of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Eurasia, the railway connecting China and Europe, has been disrupted by overspill from the war in Ukraine. Projects planned for Ukraine now have little future, and even projects between China and Russia may be in jeopardy due to sanctions. The question now is whether the BRI’s future projects in the rest of Europe will also be disrupted. Will the shocks be felt in other parts of the BRI world? These are some of the questions explored in this edition of Global China Inc. Tracker.

China’s stance of pro-Russian neutrality will further alienate it from European countries and hamper the BRI’s rollout in Europe. Remarkably, in the UN General Assembly vote on condemning Russian aggression, usually pro-Russian Serbia voted with the rest of Europe to condemn Russia. Serbia’s vote suggests even philo-Russian countries may not rejoice at an invasion. The crisis has also united the EU, bringing Putin-friendly figures like Hungary’s Viktor Orban into the fold.

As for other EU countries, France and China recently signed an agreement worth EUR 1.7 billion to jointly build infrastructure in third countries. The list included African, Southeast Asian, and Central and Eastern European countries. China’s ambiguous position on the Ukrainian war may undermine the agreement. Even if China does not materially help Russia, China’s support for an anti-NATO narrative and a broad anti-Western stance is likely to exacerbate the security discourse around BRI projects. Amid heightened geopolitical and security concerns, future collaborations with China – such as within the EU’s Global Gateway projects in third countries – will probably face greater skepticism and more obstacles.

However, the strongest negative impact will be on BRI projects in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). China may see nations neighboring Ukraine or Russia as suspectable to spillover instability, making investments too risky at present. In many CEE countries, memories of Soviet times make China’s neutrality towards Russia’s invasion of Ukraine anything but neutral. CEE governments may be less likely to conclude agreements with a China that is seen as an apologist for Russian actions.

Chinese infrastructure investments in CEE countries were low to begin with, and the relationship between some CEE countries and China was already under strain before Russia invaded Ukraine. Will the invasion be the death knell for the region’s China-led 16+1 group? Much will depend on the length of the conflict, and how far developments in the war fuel feelings of insecurity in CEE countries. And most importantly on the strength or otherwise of China’s future support for Russia.

Will what applies within Europe also apply in the rest of the world? Apparently, not. Last week, while Europe prepared for a series of summits with US President Joe Biden to discuss future coordinated responses to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China announced it will host the 14th BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Summit later this year. The theme of the summit will be “Foster High-quality BRICS Partnership, Usher in a New Era for Global Development”, a theme very much in line with the new “high-quality” BRI. On that same day, the BRICS announced the opening of their own vaccines R&D centers. The centers will initially operate online connecting facilities in the five countries and only in a second phase, move to a physical center, the location of which is still to be decided. Even though the label BRI does not appear anywhere, the connection between the above project and the BRICS summit with the BRI is evident, as is China’s determination to keep the initiative going regardless of what is happening in Europe.

The pandemics has made health related projects a core element of the new connectivity, the BRI is not the only one to have invested in that aspect. In the recent EU-Africa summit, the Global Gateway has also advanced a series of health-related projects. The first and most immediate step is for the EU to share 450 million doses of vaccines with Africa by mid-2022. Then invest EUR 425 million to help roll out vaccines in Africa. And raise over one billion of investments between the EU and its member states to support the manufacturing of vaccines (the African Union’s goal is to manufacture 60 percent of needed vaccines by 2040). Finally, the European Commission, the World Health Organization, the European Investment Bank and the African Union plant to mobilize more than EUR one billion to improve primary health care in Sub-Saharan African countries.

Meanwhile, the war will likely have a strong negative economic impact globally, as it is already doing, and may foster competition rather than collaboration between different connectivity initiatives. In times of economic pressure, receiving countries and companies will become less picky about the conditions under which opportunities present themselves. In such a context, reservations against China's pro-Russian positions will not automatically mean China loses traction in third countries. If Europeans want to compete with the BRI, it is important that Global Gateway does not fall off the radar under more immediate pressures. This is the biggest risk for Global Gateway. It has already got off to an underwhelming start. Indeed, so far, the EU-African Union summit that took place in Brussels in February has been the only attempt to give Global Gateway momentum and meaning.

Regional Spotlight: The BRI post-Russian invasion

The tragic return of war to the European continent is a reality at odds with integration and “win-win” connectivity envisaged in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). How is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine likely to impact President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy concept?

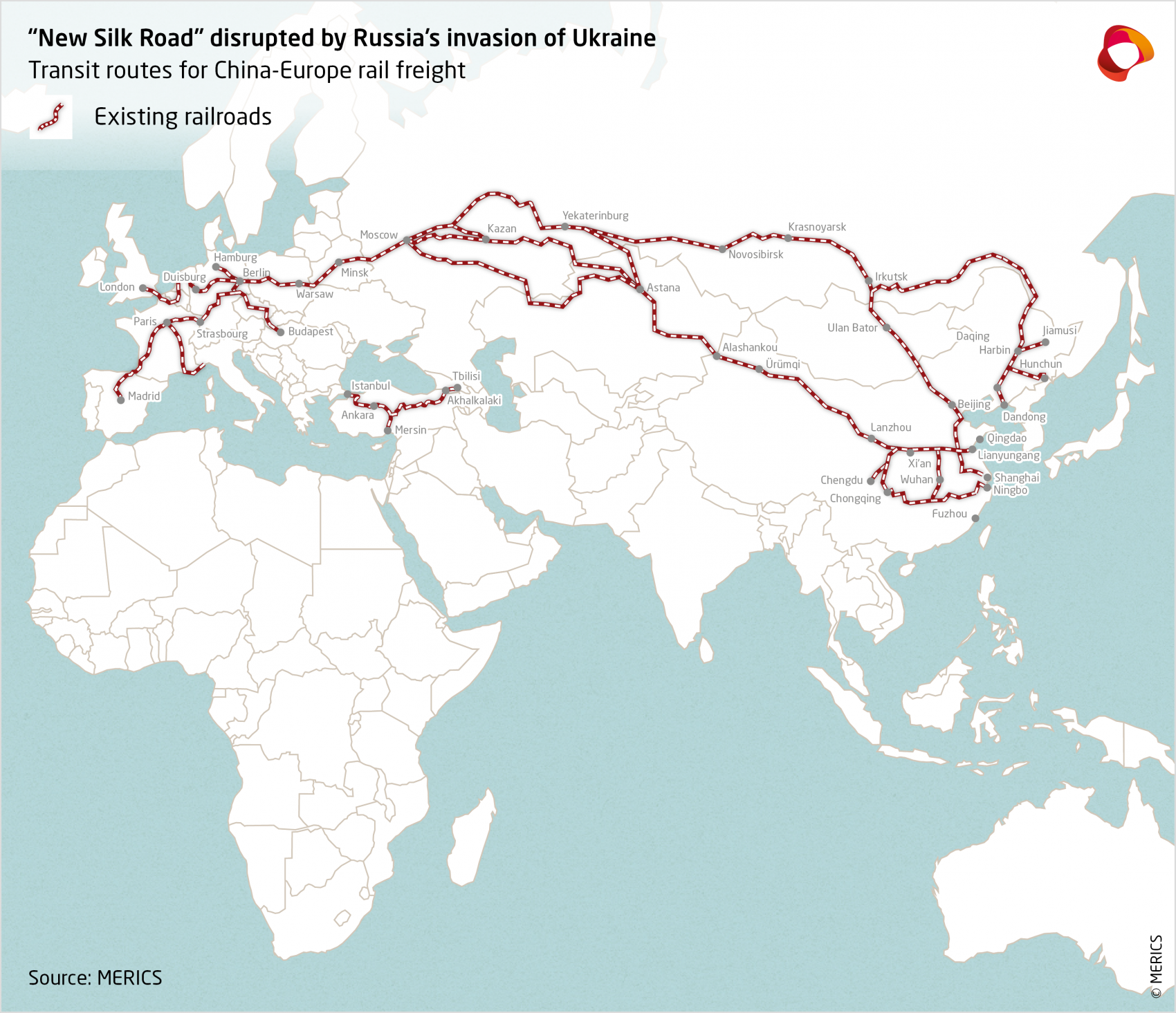

The untimely demise of the China-Europe Railway Express

Rail freight services that run between Europe and China under the banner of the “China-Europe Railway Express” will be hard hit by the war in Ukraine. Cities like Duisburg, which had high hopes for becoming a logistics hub on the “New Silk Road,” have had their dreams put on hold indefinitely.

Continental railway trade between China and Eurasia arose organically, pre-BRI, as a way to provide a faster route to Europe for manufacturers of high-value goods in central China.

After the BRI was launched in 2013, these continental trade routes became important symbols of Beijing’s wider connectivity initiative. They were heavily subsidized by China’s government to stimulate traffic, provide business for Chinese operators and a BRI public relations success.

The war’s direct impact on China-Europe rail freight will be limited; transit through Ukraine accounted for just 2 percent of railway traffic volumes between China and western Europe in 2021. The main economic impact of the war comes from Western sanctions against Russia.

Most rail freight from China must transit Russia on its way to or from Europe. Although there is no ban on transport through Russia, the country’s exclusion from the SWIFT payment system and companies’ fears about being caught on the wrong side of sanctions have already led to widespread cancellations. One of the route’s largest customers, networking gear maker Zyxel Communications Corp, announced it was suspending freight through Russia soon after the invasion in anticipation of disruptions. Several large logistics companies and service operators have also halted operations through Russia, some of them citing ethical concerns.

On paper, disruptions to transit through Russia could provide opportunities for Turkey and the so-called “Middle Corridor” countries in the Caucasus or Central Asia to ship more goods to Europe. Some freight has indeed been rerouted through Turkey, but the reality is that these routes are severely underdeveloped, and do not provide a viable alternative.

Disruption to China-Europe rail freight is low on the list of economic problems caused by the Russian invasion. Continental rail freight represents only a fraction of trade between Europe and China, despite the dramatic growth in traffic (from a very low base) and much media attention. However, the symbolic weight of the New Silk Road was always greater than its economic importance.

The growth in traffic during the pandemic proved the China-Europe route was a viable alternative for supply chains, but Russia’s invasion has made that success story short-lived.

The BRI in Russia may expand but will remain resource-focused and limited

Russia’s isolation from the global economy is likely to enhance the BRI’s role there, though economic cooperation will not be on Moscow’s terms. Opposition to US hegemony is the firm foundation of the Sino-Russian “no-limits” partnership, and the reason Beijing has not wavered from its position of pro-Russian neutrality since the war started. However, the economic dimension of the Sino-Russian BRI relationship is a top-down and politically driven imposition that has borne few fruits beyond oil and gas sectors.

Although trade between Russia and China surged in 2021, this was largely due to higher commodity prices and Beijing’s decision to substitute Russian for Australian coal. Sino-Russian trade is highly focused on fulfilling China’s energy needs, as too is China’s investment and cooperation on infrastructure. The Sino-Russian record on infrastructure cooperation is marked by announcements that go nowhere. Despite ostensibly warm political ties, the Chinese side has been historically unwilling to make concessions on BRI projects.

After the 2014 annexation of Crimea, China and Russia signed the Power of Siberia megaproject, creating the impression that Beijing was rushing to Putin’s aid. However, this deal was in line with expected developments, and post-2014 cooperation was marked more by opportunism than altruism on Beijing’s part. BRI projects in Russia have also been hindered by Russian requirements that aim to protect domestic industry. With the Russian economy cut off from global financial markets, it is possible that Moscow may become more willing to make concessions to China.

However, the terms will need to be good - China’s utmost concern will be protecting its own economy from the effects of the war. Growth targets for 2022 are already threatened by disappointing domestic demand, Covid-related difficulties, and soaring commodity prices. Russia’s isolation will bring the Russian economy closer to China by necessity and leave room for the BRI’s expansion. However, Russia’s dependency on China will increase. Beijing will take advantage of cheap commodity prices but is unlikely to throw any substantial economic lifelines to Moscow.

Beijing embarked upon a course of greater caution with regards to external finance before the invasion for sound policy reasons, so we should not expect a major redirection of finance to the beleaguered Russian economy. President Vladimir Putin may well get “mate’s rates” on BRI deals, but he certainly won’t ride for free.

Putin’s invasion destroys the prospect of a BRI renaissance in Ukraine

It should not be forgotten that Beijing also has interests in Ukraine and was trying to expand its presence there. Prior to Putin’s invasion, the BRI was having a mild renaissance in Ukraine. In late 2020, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s government signed a “Cooperation Plan” on “jointly building” the BRI with Beijing, marking a step forward for Ukraine’s participation in the BRI. In 2021, Ukraine and China signed another agreement on infrastructure cooperation, paving the way for Ukraine to access roughly USD 1 billion worth of low-interest loans.

Political frustrations have dogged the rollout of BRI-related infrastructure in Ukraine, which was originally Beijing’s preferred BRI partner in Eastern Europe. However, Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea shifted attention to Belarus. China swallowed its losses, deferred to Russian interests, and maintained friendly ties with Ukraine though bilateral co-operation remained superficial. On the Ukrainian side, there was little enthusiasm, given viable Western alternatives and Ukraine’s requirements for open bidding processes.

In trade, the Sino-Ukrainian economic relationship was deeper. In the first half of 2021, China did USD 9 billion worth of trade with Ukraine, outstripping Ukraine’s combined trade with Poland (USD 5.6 billion) and Germany (USD 3 billion). Beijing’s demand for grain and its efforts to diversify supply chains have driven this trend: food products accounted for 53.1 percent of exports to China in the first months of 2021.

For Beijing, Putin’s invasion of an agricultural powerhouse is probably the most economically painful aspect of the conflict. Nonetheless, there were promising signs for the BRI that suggest the conflict is likely to be felt as a setback by Chinese companies such as Power Construction Corporation of China that were eyeing Ukraine as a construction and renewable energies market.

Russia’s hand in Central Asia weakens, opening more space for the BRI

Central Asia is another important BRI region to consider. The region’s former-Soviet countries of Central Asia vary greatly and have very different economic profiles. China and Russia have largely kept up a neat division of labor across the region. Moscow maintains tighter political, cultural, and linguistic ties with Central Asian countries, while China takes the role of economic engine.

However, Russia has maintained its economic weight as a labor market for Central Asian workers. Remittances from Russia made up a quarter of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP in 2020; it is the most remittance dependent Central Asian economy. As sanctions sap the Russian economy, the IMF predicts a 33 percent decline in remittances that will weaken Russia’s already declining economic influence on the region.

Central Asian governments’ responses to the war range from cautious support to awkward neutrality. Among populations, opinions are complex and divided. Up until now, Russia’s hegemonic influence has not allowed much room for official criticism of Putin. However, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and its growing economic irrelevance in the regions will inevitably alter the strategic balance in Central Asia, enabling Beijing to strengthen its hand.

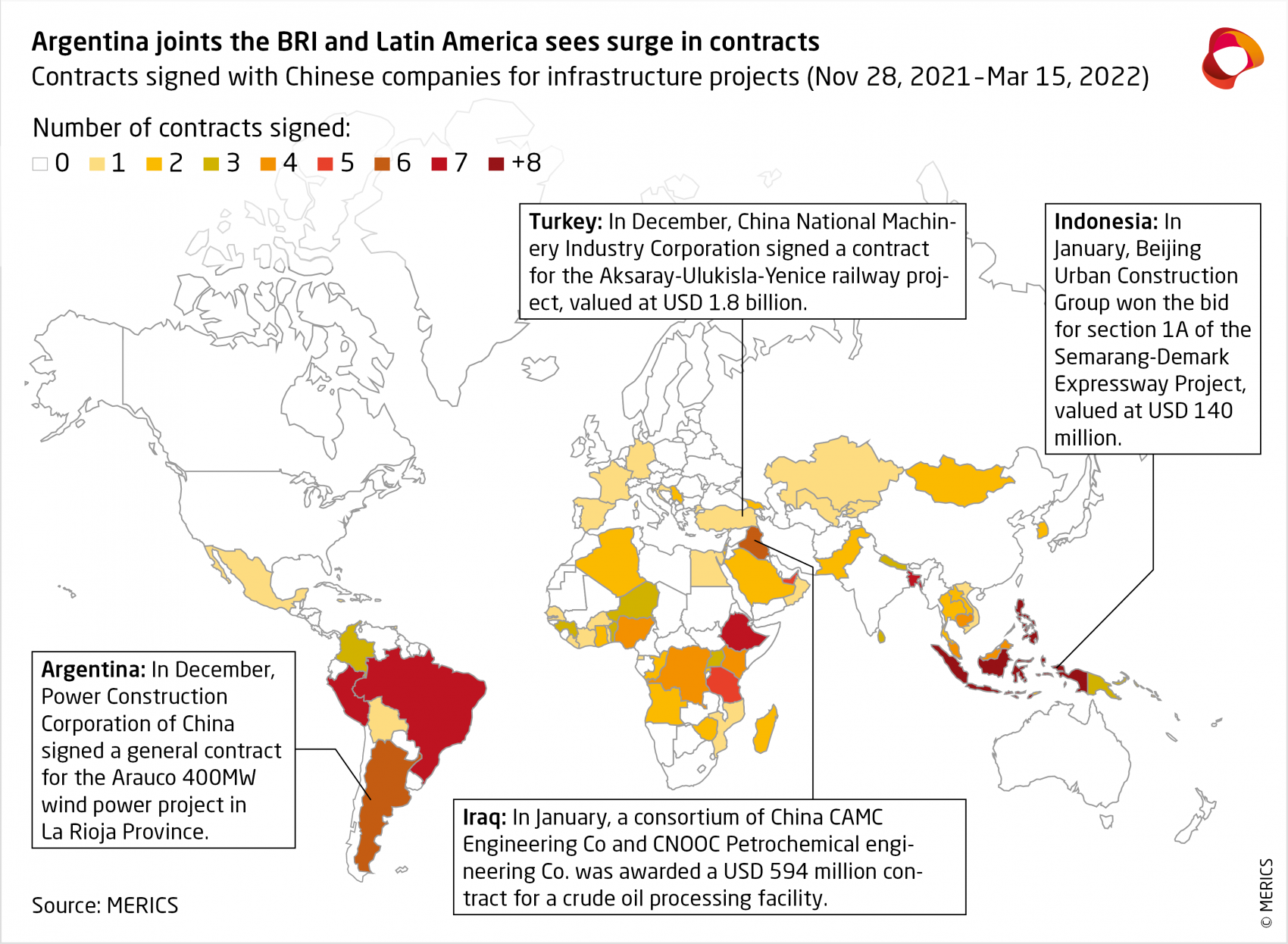

The conflict and polarization will not halt the BRI’s global expansion

Putin’s invasion has disrupted the BRI’s vision of a post-Western, yet peaceful “community of common destiny.” Instead, it has led to greater unity among Western powers, deeper global divisions, and serious disruptions to the world economy. Fallout from the war will weigh on China’s economy and hasten the trend towards more restricted and cautious, external finance for the BRI. However, China Inc. will not disappear from the global stage. Infrastructure will still need to be built and Chinese construction companies still need to find contracts to pay their bills.

In the longer-term, sanctions against Russia could accelerate decoupling between the West and China, hastening the development of alternative ecosystems. The BRI will doubtless play an important role in this process. The political significance of the BRI as a tool for demonstrating China’s leadership of the developing world will also deepen. Contrary to Western perceptions of an international front against the war, many countries in the Global South maintain a neutral stance on the Russian invasion. Beijing will continue to take advantage of anti-Western sentiments in the Global South, wielding the BRI as an example of its alternative brand of development.

China’s “Belt and Road Family” is still growing

In February, Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández made state visits to Russia and China. There, Fernández sought to deflect from domestic economic troubles and opposition to the terms of the latest loan-restructuring talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in which he had won a USD 44.5 billion standby loan to avoid a repayment default. In Moscow, Fernández said Argentina “has to stop being so dependent on the Fund and on the United States and has to open up to other places.”

Fernández then traveled to Beijing to witness the signing of a “Memorandum of Understanding” (MOU) marking Argentina’s symbolic entry into the “big family of the Belt and Road Initiative.” Argentina’s entry to the BRI family came with a package of USD 23.7 billion in infrastructure deals and Beijing’s reiteration of support for Argentina’s claim to the Falkland Islands.

The BRI family boasts 148 members

The official government website for the BRI lists countries that have signed BRI cooperation agreements with China; it is the nearest thing to an official list of BRI countries that is available. With the addition of Argentina, it now lists 148 countries worldwide. At least 130 countries have signed MOUs similar to the one recently adopted by Argentina - an MOU on “jointly constructing the ‘One Belt One Road’” (共建“一带一路”谅解备忘录). A further 18 countries have signed unspecified “cooperation documents” (合作文件) but there is no public record of an MOU. Such “cooperation documents” (合作文件) are generally considered to be a lesser commitment than an MOU, but this is not necessarily the case.

Russia, for instance, is one of the 18 countries that do not appear to have signed a BRI-related MOU. However, this is more likely indicative of Russia’s special relationship with China as there is a plethora of other Sino-Russian cooperation documents and high-level endorsements covering the BRI. Neither does Ukraine appear to have signed a BRI MOU, though it signed a “cooperation plan” (合作规划) in December 2020, which is a subcategory within China’s “cooperation documents.” Such plans are more typically signed after a MOU, in order to detail specific projects and project timelines.

Similarly, Pakistan did not sign a MOU endorsing joint construction of the BRI until 2017, at the first BRI forum. Yet the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor was declared a BRI “flagship” project in 2015, and Pakistan has been supportive of the BRI since its inception in 2013. Beijing has not publicly clarified a hierarchy of BRI cooperation documents and there are significant variations within this system. However, signing an intergovernmental MOU is the semi-standardized step for officially “joining” the BRI.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) is a mutual statement of intent. An instrument of “soft law,” it provides a written, signed record, but it is not legally binding. In fact, BRI MOUs include a section specifying that they do not constitute an international agreement.

MOUs are a prominent feature of Chinese diplomacy and international business, reflecting a characteristic preference for informal bilateralism. The BRI is often misunderstood as a forward-planned grand strategy but is in fact a series of ongoing experiments. MOUs pro-vide the flexibility required for China’s ad-hoc approach.

MOUs also tend to work in the stronger party’s favor, as they can shirk obligations while still establishing preferred norms to refer to as necessary. China’s BRI MOUs establish a hub-and-spoke network of informal agreements with China at the center.

BRI MOUs act as a symbolic endorsement of Beijing’s global leadership

Italy garnered a wave of Western media attention when it signed a BRI MOU in March 2019, becoming the first G7 country to officially join China’s global initiative. In fact, Italy was the fifteenth EU member state to join the BRI, but the majority of those signed MOUs in 2015 and 2017 when Western opposition to the BRI was still embryonic.

By contrast, Rome’s populist, Eurosceptic government opted to join the BRI shortly after the European Commission labeled China a “systemic rival.” Italy’s move prompted multiple warnings from Western leaders. Although the Sino-Italian MOU’s text was deferential towards EU initiatives and interests and contained merely general hopes for cooperation, its significance lay in Italy’s decision and timing.

For China, the primary purpose of BRI MOUs is to amplify and legitimate to the BRI in the eyes of both domestic and international audiences. Joining the BRI is an endorsement of Beijing’s global leadership, and a concession that many Western countries have been reluctant to make.

BRI MOUs offer a low-stakes gamble for partner countries

For most countries, joining the BRI is a light-weight endorsement. It does not imply taking a seat within a guiding international institution. Nor do they suddenly qualify for access any specified funds or channels of communication. It is a provisional and exploratory framework. Most signatory countries anticipate that signing a BRI MOU will pave the way for investment from China. Some governments, such as Italy and Argentina have also used BRI MOUs to signal foreign policy independence and enhance their international significance.

Does signing a BRI MOU paves the way for greater Chinese investment? Given the ad hoc nature of the BRI, there is no one-size-fits all answer: Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania signed up in 2015 yet have seen few concrete rewards for their early enthusiasm. Brazil and Turkmenistan have not signed MOUs, but have obtained Chinese investment. Some smaller developing countries have found joining the BRI is an obligation and prerequisite for harmonious relations with Beijing.

BRI MOUs are often signed alongside project-specific MOUs between ministries and companies that flesh out further cooperation plans. Legally binding agreements are the next step but whether such contracts actually materialize is highly context-specific. MOUs never guarantee investment from China, though they are a valued step towards deepening engagement.

Italy faced minimal consequences (good or bad) from joining the BRI, despite the furor at the time. Several related MOUs have come to fruition, while other deals have failed to materialize, notably for the ports for Triste and Genoa. Ultimately, Italy’s move was an attempt to carve out a niche in Europe-China relations that failed to pay off and had few long-term repercussions.

In 2021, seven countries signed on, all African holdouts; two of them had switched their diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to Beijing in recent years. So far this year, China has picked up the pace and already signed up Nicaragua, Syria, and Argentina to the BRI, though it will be a challenge to beat its 2021 performance.

Of the UN’s 193 UN member states, only 47 have not signed a BRI-related agreement with China. Most non-signatories in Eurasia and Africa remain unlikely to ever join for geopolitical reasons, for instance India, Japan, and many EU countries. Most of the remaining potential signatories are in Central and South America.

The remaining holdouts, especially important ones like Brazil, find themselves better placed to sign up for a high price than earlier signatories. Rome handed Beijing a big symbolic win without receiving much in return, whereas Argentina appears to have walked away with a genuine reward for its long-withheld signature (with the caveat that MOUs lack concrete guarantees). As the battle of narratives between China and the West deepens, Beijing’s support in the Global South and for the BRI has become even more important.

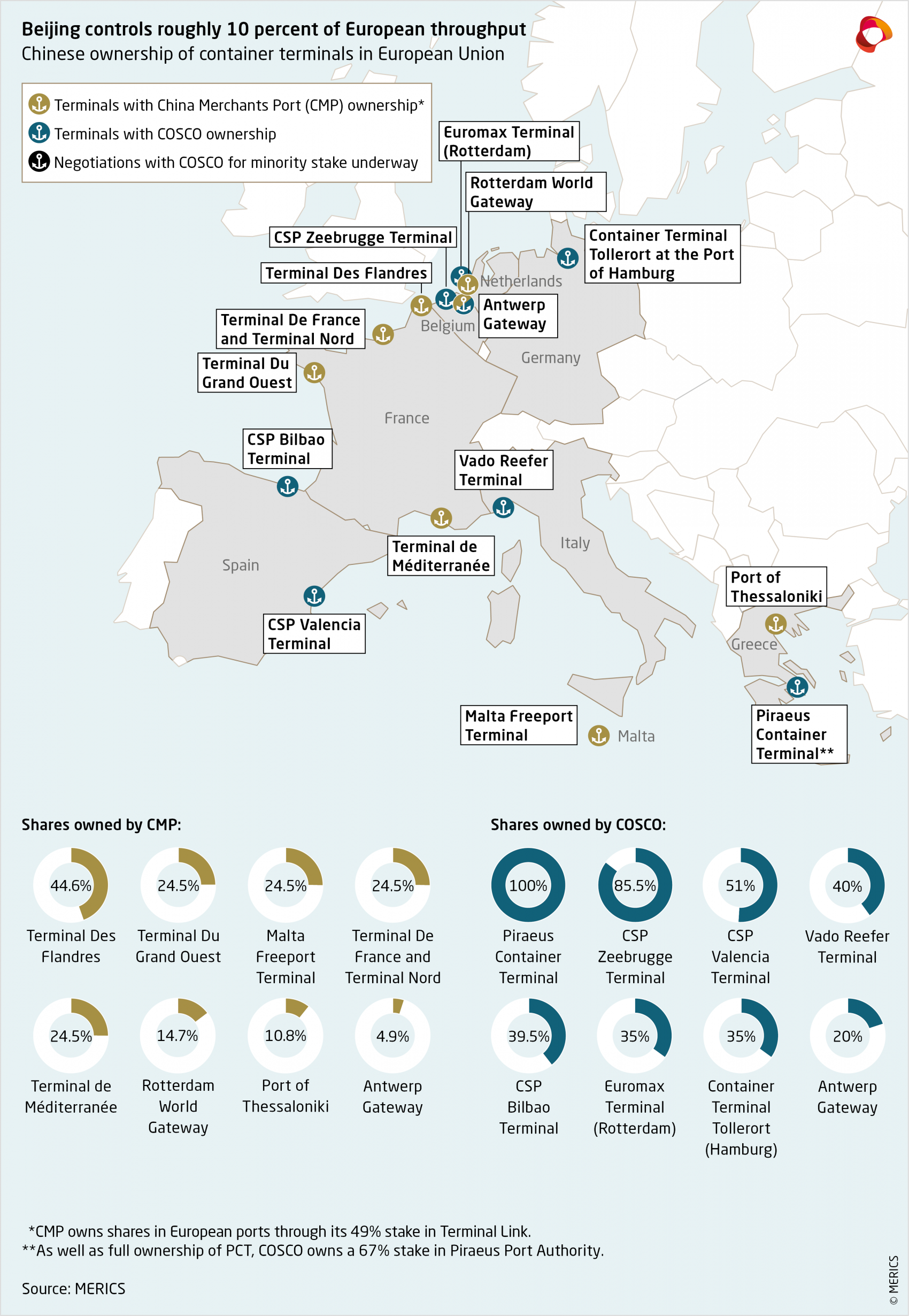

Key player: Getting to grips with COSCO and its value chain

From a European perspective, COSCO, China’s maritime shipping champion and the world’s fourth largest shipper, presents several challenges worth considering. But first, it is worth noting that European shippers currently lead the world in market share and total shipping capacity. The world’s three largest shippers by twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) capacity (the commonest measure of how many containers a fleet can move) are Mediterranean Shipping Company (Swiss/Italian), MAERSK (Danish), and CMA CGM (French). COSCO ranks in fourth place, followed in fifth place by Hapag-Lloyd (German). COSCO is not a challenge to European firms because of its size. The risks it poses stem from unfair advantages in its home market and the risk of market distortions throughout the shipping industry as a result.

First, COSCO presents a unique challenge in the world of logistics. The state-owned company is also a state-owned, vertically integrated value chain that can exert monopolistic dominance, and a protected home market advantage, in its activities in third markets. To compete with COSCO is to compete with the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) - the embodiment of China Inc.

- COSCO makes some of its own ships, as well as being a major customer of China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC), China’s SASAC-owned monopoly shipbuilder, and its subsidiaries

- CSSC and COSCO, in turn, buy the bulk of their steel from state-owned suppliers Baosteel, Sinosteel, and the Wuhan Iron and Steel Group, which all use coal and iron sourced from SASAC-owned mining and trading companies

- COSCO uses ports and terminals that are either owned and operated by COSCO itself, or through the SASAC-owned China Merchant Group

- Even the shipping containers used by COSCO, and everyone else, are almost all made in China by Chinese-owned companies, all of them state-owned except for CXIC containers.

- The entire value chain is financed by China’s state-run banking system

COSCO’s state-owned value chain offers many ways to hide state support

COSCO’s state-owned value chain is rife with opportunities for hidden state support. For example, if SASAC wanted to support COSCO indirectly, it could provide free land for coal producers, give preferential loans to steel makers, and/or impose lower profit margins on its shipbuilder or container makers. All these steps would bring benefit to COSCO downstream. Support upstream would allow COSCO to offer lower prices and grab market share from foreign shippers who are bound by market forces and competition law in their home markets.

Furthermore, China has an unlevel playing field in maritime shipping (see here for MERICS analysis on the topic) which is slanted to COSCO’s benefit. For instance, European companies cannot invest in subsidiaries in China to conduct domestic shipping, whereas COSCO can invest in subsidiaries in Europe to perform domestic shipping. The imbalance allows COSCO to compete for market share through those subsidiaries within the EU, while European competitors are blocked from doing the same in China. Meanwhile, the lack of domestic competition means COSCO has a protected home market where it can charge higher margins that ultimately subsidize its activity abroad.

After benefitting from these supports, COSCO enjoys an additional boost from the BRI, in diplomatic support to secure projects plus advantageous loans below-market rates from BRI-related policy banks. All this has allowed COSCO, and China Merchants Port (CMP), to drastically expand their market share of port ownership worldwide. The expansion has not been limited to greenfield projects in new and existing terminals. It has included brownfield investments to build shares in ports worldwide, sometimes the controlling share, or even complete ownership. COSCO’s and CMP’s investments and outright ownership of ports has extended into Europe (see exhibit 3 above).

The long-term potential risks of this cocktail were spelled out in clarity in the 2020 European Union Chamber of Commerce report on the BRI, The Road Less Travelled:

“…there is genuine concern that these ports are being developed under the same kind of unfair conditions that can be observed in China’s shipping sector. The further expansion of scale of Chinese companies under the BRI does not help to build a positive perception among European players, particularly when certain undesirable practices continue in China. However, the greatest concern is the emergence of the still-growing SASAC monopoly of the shipping sector’s value chain, as it raises serious questions about how global competition can be maintained and casts the maritime aspect of the BRI in a grim light.”

All these advantages in its home market and through the BRI mean it is little wonder that COSCO has roughly doubled its annual revenue from 2016-2020, and its footprint has exploded onto the global map in recent years. Grappling with COSCO, and the rest SASAC’s vertical and integrated monopoly of the value chain and BRI-related benefits, will be a test of Europe’s ability to address the imbalances and distortions emanating from China Inc. The challenges involved demand serious consideration by the EU and its member states.

Global China Inc. Updates

BRI POLITICS

France and China to cooperate on development projects worth USD 1.7 billion in third countries

In February, following a virtual meeting between Xi Jinping and French President Emmanuel Macron, Paris and Beijing agreed to jointly build seven infrastructure projects worth over USD 1.7 billion. The groundwork for this development was laid in the 2015 Sino-French joint declaration on cooperation in third markets and seven years of discussions. The list of projects has not been published, but French newspaper Le Monde claims that six of the seven projects are in Africa - a water treatment plant in Senegal, 3 hydroelectric projects in Gabon, port renovation in Ivory Coast, and a road in Guinea, plus a wind energy project in Greece.

In recent years, enthusiasm for China-EU cooperation on infrastructure has waned in favor of competition. The EU’s Global Gateway, which seeks to leverage the EU’s own connectivity toolkit for strategic ends, has eclipsed efforts such as the China-EU connectivity platform, which seeks to foster cooperation on the same topic. However, France continues to quietly cooperate with China in state-led projects that further the fortunes of French companies overseas.

China strengthens ties with Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is China’s biggest supplier of oil, and the two countries have become increasingly close over the past two years. In February, China Merchants Capital and the Silk Road Fund were part of an investor consortium that acquired a 49 percent stake in Aramco Gas Pipelines Company for USD 15.5 billion.

The economic relationship has become increasingly diversified, in line with Saudi ambitions for a post-oil future and Chinese interests in the Saudi renewables and construction markets. In February, Jinko Power Technology made a winning USD 209 million bid to develop a solar project in Saudi Arabia. In March, Saudi and Chinese firms formed a joint venture to manufacture military drones. Around the same time, three tech firms from Saudi Arabia and China signed an agreement to collaborate on the development of space technologies and artificial intelligence.

Saudi Arabia is also helping facilitate Chinese ambitions to internationalize the RMB; in March, reports emerged that Saudi Arabia is in talks to price some of its oil sales in RMB. After Riyadh issued an invitation in March, Saudi Arabia is even rumored to be the destination of Xi’s first international trip since January 2020.

DIGITAL, HEALTH AND TECH

Egypt and China sign agreement on vaccine cold storage

In January, Chinese vaccine maker SINOVAC Life Sciences Co., Ltd. signed a cooperation agreement with Egypt’s Holding Company for Biological Products and Vaccines (VACSERA) to establish a cold storage facility for vaccine storage in Egypt. VACSERA has manufactured around 30 million doses of Sinovac’s COVID-19 vaccine after signing agreements with Sinovac in 2021. VACSERA is expected to manufacture a 100 million more doses this year. The number falls well short of Egypt’s goal of manufacturing one billion doses annually, but it does advance Egypt’s ambition to become a regional Covid-19 vaccine hub.

Huawei continues energy pivot alongside global 5G rollout

In February, Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd signed cooperation agreements with Egyptian companies to promote digitalization in the oil and gas sector using Huawei systems. Huawei has shown increasing interest in the energy sector. It established Huawei Digital Power Technologies in June 2021 in an attempt to take advantage of growing demand for clean energy and diversify beyond the commercial damage caused by US sanctions. In March, Huawei Digital Power signed a cooperation agreement with Meinergy, a Ghanaian power company, to build what may become the largest solar storage project in Africa. Huawei has also had some more limited success in its signature domain of 5G technology. In December, the first commercial 5G network in Bangladesh came online using technical support from Huawei.

Belt and Road in space: China releases new space white paper

On January 28, the State Council Information Office released a new white paper detailing its Five-Year Plan for space exploration. The white paper lists ambitious projects, and lays out China’s ambitions for space governance and the integration of its space sector with the wider economy. The BRI gets several mentions, and the paper emphasizes cooperation with BRI partners in space through projects like the Pakistan Space Center and Egypt's Space City.

ENERGY

China’s State Grid wins contract for important wind project in German North Sea

In March, European transmission network operator Tennet issued a notice confirming that the contract for BorWin6, a grid connector for offshore wind farms in the German North Sea, had been won by an international consortium including China Electric Power Research Institute (CEPRI). CEPRI is a subsidiary of the State Grid Corporation of China, the largest utility company in the world. In 2018, a German government-owned bank blocked State Grid’s attempt to purchase a minority stake in grid operator 50Hertz over concerns about Chinese ownership of critical infrastructure.

China’s nuclear ambitions furthered with Argentina deal

In February, shortly before the Argentine president officially joined the BRI during a state visit to Beijing, the two countries also signed an agreement to construct Argentina’s fourth nuclear power plant. It will use Chinese finance and technology from China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC). The USD 8 billion plant, Atucha III, will be the third nuclear power plant built outside of China using the home-grown Hualong One reactor. The other two are both in Pakistan. Karachi Nuclear Power Plant contains two Hualong One reactors, while another is under construction at the Chashma Nuclear Power Plant.

Chinese and French companies finalize USD 10 billion oil production deal with Uganda and Tanzania

In February, TotalEnergies SE and its partner China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) reached a deal with Uganda and Tanzania to invest more than 10 billion USD in developing Uganda’s Lake Albert development project. The project will consist of oil fields, processing facilities, and one of the world’s largest export pipelines, running from landlocked Uganda, through Tanzania to the Indian Ocean. French and Ugandan environmental groups have confirmed they will continue legal action against the plans, saying the oil wells and pipeline would have catastrophic environmental consequences.

Chinese company to build plant in Finland to meet electric vehicle battery demand

In December, major Chinese battery material producer CNGR Advanced Material Co Ltd signed a shareholder agreement with Finnish Battery Chemicals (FBC) to establish a joint venture named Project 1 Oy. The joint venture will construct a EUR 200 million facility to produce lithium-cobalt-manganese oxide (NCM) precursor for the European electric vehicle (EV) battery market.

Tsingshan Holding Group crashes metals market after spiking nickel prices

The London Metal Exchange (LME) suspended trading on March 8 for the first time since 1985 to limit contagion caused by Tsingshan Holding Group, the world’s largest producer of nickel and steel. Tsingshan’s billionaire owner Xiang Guangda had taken a massive short position on the price of nickel, betting it would fall. Instead, prices climbed sharply higher after the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the world’s third largest nicker supplier, which was then hit by punishing sanctions. Tsingshan tried to buy back its forward contracts, causing the nickel price to double in the space of a few hours. The LME resumed trading a week later after Tsingshan announced that it reached a “standstill agreement” with its creditors while it resolved its margin positions and settlement requirements. It is likely that Beijing will have to step in to rescue Tsingshan, which is a key BRI player with massive nickel investments in Indonesia.

Top battery maker urges China to secure lithium supply chain and new contracts show the process is underway

The chairman of the world’s largest battery maker, the Chinese company Contemporary Amperex Technology Ltd. (CATL) called on the Chinese government in March to strengthen its lithium supply chain, citing surging demand. Chinese companies appear to have already heeded the call; major lithium investments have been announced every month since at least September last year. In December, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt paid USD 422 million to acquire the Arcadia hard rock lithium mine in Zimbabwe. In January, Zijin Mining Group Co. Ltd launched its first lithium exploration project in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and in February, Sinomine Resources Group announced that it had spent 180 million USD to gain control of the Bikita lithium mine project, also in Zimbabwe.

TRADE AND FINANCE

Xi Jinping pledges USD 500 million in grant assistance to Central Asia

Xi Jinping pledged USD 500 million in grant assistance to Central Asia during the January 25 virtual summit held to commemorate 30 years of relations between China and Central Asian countries. He said the funds were to “support livelihood programs.” The grant shows China’s growing economic role in Central Asia and reveals how its development assistance is evolving. Development finance has typically been aimed at infrastructure projects whose construction generated revenue for Chinese companies. However, in recent years the grant element of Chinese development finance has been steadily increasing. The Central Asian grant focuses on social programs, a shift towards “softer” elements of development that remains unusual for Chinese development aid.

Mammoth Asia-Pacific trade agreement enters into force; members include China but not the US

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) entered into force on January 1, 2022. The mammoth free trade zone agreement, signed in November 2020, brings together 15 countries with roughly 30 percent of global GDP and one third of the world’s population. It consists of the ten Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) plus Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. Often framed as “China-led” and in opposition to the Obama-era Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, RCEP was in fact brokered by ASEAN. Nonetheless, RCEP will indeed help accelerate Asian economic integration without the United States, and strengthen China’s relations with its neighbors.

TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS

Chinese consortium wins USD 2.76 billion contract to develop first portion of Philippines railway

In January, the Philippines signed a USD 2.76 billion USD contract for the first 360 kilometers of the PNR Bicol rail project with a Chinese joint venture of three companies, including China Railway Group Ltd. China’s ambassador to Manila said it was the “highest funded” government-to-government contract that China and the Philippines have signed.

Controversial China-built road finally opens to traffic in Uganda

The Kampala-Entebbe Expressway opened to traffic in January. Built by China Communications Construction Co. Ltd with a USD 350 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China, work on the road began in 2012. It has missed its deadline by several years. Critics have objected to the high cost of the 51-kilometer toll-road, especially given the projected lack of traffic along the route.

French companies mull takeover of Chinese port contract in Tanzania

Tanzanian Newspaper ‘The Citizen’ reported in February that unnamed French companies will start talks with Tanzania’s government about construction of the revived Bagamoyo port project. A framework agreement for the USD 10 billion project was signed in 2013 with China Merchants Holding International (CMHI), but negotiations were shelved in 2019. Tanzania’s president said at that time that China’s conditions were “exploitative and awkward.” However, China may still be in with a chance of developing the port as Tanzania’s new president Samia Suluhu Hassan hinted in 2021 that new talks China Merchants were underway.