China’s multi-purpose export controls raise pressure on Europe to derisk

In the first in a series of three articles about Beijing’s rare-earths export controls, Rebecca Arcesati and Jacob Gunter argue that the new licensing rules have disrupted supply chains around the globe—and that Europe cannot rely on market forces or Beijing’s whims for a fix.

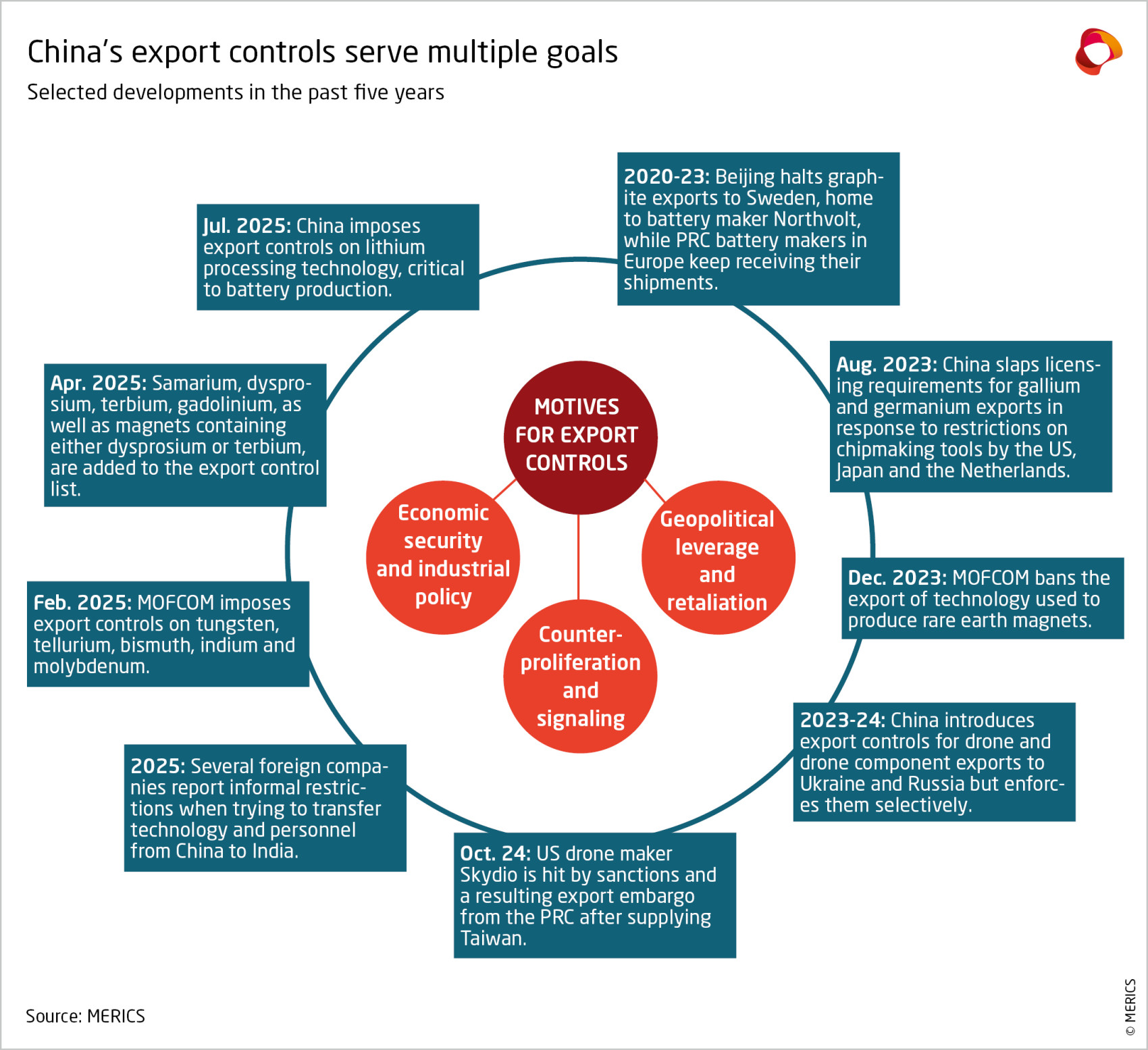

China has reacted to the Trump administration’s tariffs by shifting its export-control strategy from eying a narrow set of items in the name of national security to targeting entire sectors and value chains on geopolitical grounds. Beijing’s controls – introduced in April on rare earth elements (REEs) such as samarium (essential for aerospace) and terbium (found in naval sonar systems) – have not only wreaked havoc on US supply chains, but on European ones too. Europe must seize this moment to advance its economic “derisking” from China.

Beijing’s foreign economic statecraft long relied on traditional legal trade-defenses such as tariffs, import and export quotas, and sometimes on extralegal ones – like boycotts organized by the Chinese Communist Party. These measures were usually applied on a bilateral basis – for example, tariffs on Australian barley, restrictions on group tourism to South Korea – and typically in retaliation against a given actor. Like other countries, China used to apply export controls on weapons, nuclear and biochemical items, and a limited number of dual-use technologies. But these controls now cover many more items and are enforced en masse.

This expansion seemed to be motivated by a desire to counter other countries’ trade measures against China. The controls on REEs and certain REE magnets were introduced in retaliation to the Trump administration’s “Liberation Day” tariffs and played a critical role in prompting the US into negotiations with China. Beijing also sought to exploit its new measures ahead of July’s EU-China Summit, trying to get the EU to drop its countervailing tariffs on subsidized Chinese electric vehicles. Unlike Washington, which loosened restrictions on NVIDIA’s H20 AI chips and other items, Brussels did not cave in.

Beijing’s measures are designed to maintain dominance in REEs

Another motivation was to maintain industrial dominance. China’s export control regime is unique in that it is also aimed at retaining innovation capacity, even in civilian technologies like LiDAR and batteries. For REEs, Beijing’s restrictions cover not only minerals, but also processing technology used for manufacturing magnets (on top of an existing export ban on REE processing and refining equipment), making it more difficult for other countries to develop their own capacities. Even REE experts are closely watched.

Thirdly, the measures were designed to support production and investment in China. One way for foreign companies to avoid the licensing requirements would be to produce more intermediate or finished products in China for export. This is possible for civilian applications, although the ongoing trade and technology tensions between China and the US and its allies would make such moves risky: No company would want to invest only to face new export restrictions from China or import tariffs elsewhere.

Finally, REEs and permanent magnets have important military uses and are vital for weapons production—raising the possibility that Beijing’s measures also aim to weaken the transatlantic defense-industrial base or limit Western support for Ukraine in the war against Russia. China’s government did tell the EU that it does not want Russia to lose the war.

China’s systemic export controls have disrupted both civilian and defense companies in Europe. In June, for example, the European Association of Automotive Suppliers reported that production lines were shutting down and more were expected to do so as REE inventories diminished. Companies have since told MERICS that access has improved again, but they remain worried. China appears to be approving export volumes to meet manufacturing demand, but not to allow stockpiling. Western arms makers have had a tougher time securing licenses and reports indicate that Beijing is maintaining this squeeze.

Licensing system creates huge risks for first movers outside China

Licensing allows Beijing to control the access of individual companies to REEs at will, leaving European companies in a perpetual grey zone. As a result, the first-mover disadvantages are considerable, with risks and costs outweighing any incentives for foreign companies to enter the REE market. The extraction and processing of critical raw materials require massive investments, while their profitability remains heavily dependent on China. Beijing would only need to temporarily loosen export licensing to boost the competitiveness of Chinese exporters – and once again rapidly price foreign companies out of the market.

As Europe cannot rely on market forces or Beijing’s whims, policy intervention to drastically reduce European REE dependencies, starting from the swift implementation of the Critical Raw Materials Act, is the best option. Decisive action would not only jump-start European REE capabilities but also signal to China that the “weaponization” of trade will only strengthen European resolve to pursue even more aggressive economic derisking, perhaps deterring Beijing from similar moves going forward. Europe should place no confidence in concessions or the recently strengthened export control dialogue with China – both options would keep entire European industries hostage to Beijing’s goodwill.

The EU could opt for subsidies, financing and regulatory support to help companies diversify REE sources away from China, or introduce import quotas that would force European companies to source a fixed proportion of REE from non-Chinese producers. Governments could also underwrite REE production by acting as buyers of last resort at set prices – much like Washington has done with Mountain Pass, the only REE producer in the US. All these options would, of course, come with costs for governments and taxpayers as well as companies and consumers. But the cost of European inaction would be far greater.