Many countries launch new trade measures – but China’s exports just keep growing

The MERICS Trade Defenses Map sheds new light on Beijing’s record trade surplus. Jacob Gunter and Claus Soong argue the US has weakened the global push to curb Chinese exports.

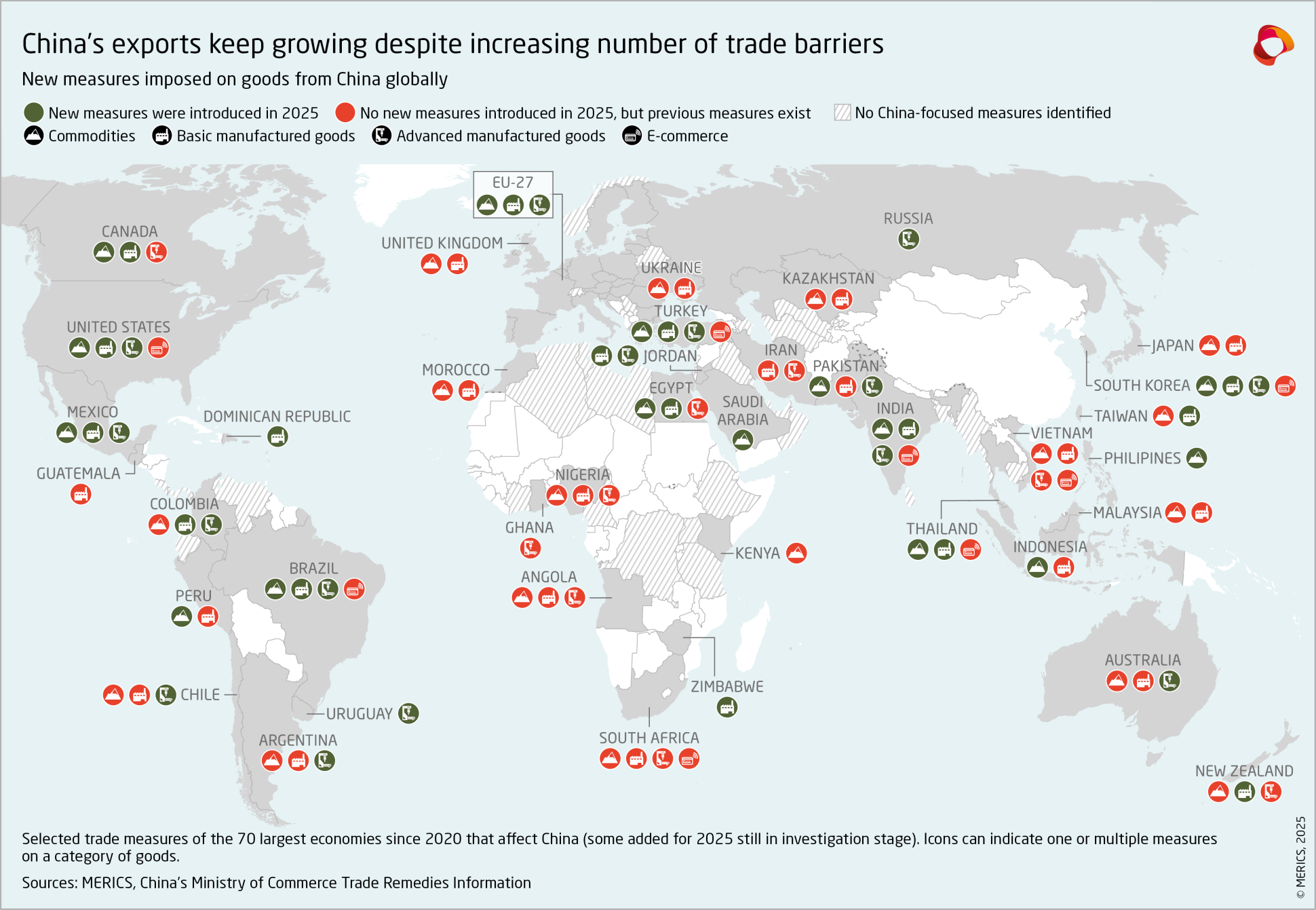

A remarkable fifty-two of the world’s 70 largest economies (including the EU-27) in 2025 responded to market distortions from China’s export glut by launching new trade defense measures and investigations, the MERICS Trade Defenses Map shows. But most of these moves proved insufficient, as China’s industrial overcapacity drove its trade surplus up 20 percent to a record 1.2 trillion USD – an especially striking increase given that exports to the US actually fell following Washington’s imposition of almost-uniquely muscular tariffs.

Governments are recalibrating their trading relations in favor of China

This faltering commitment to protecting most home markets from low-cost Chinese imports came as US President Donald Trump also imposed tariffs on trading partners other than China. The data underlying the MERICS Trade Defenses Map indicates that many countries that had previously raised barriers against China slowed or even stopped the rollout of new measures during 2025. This trend suggests that governments are recalibrating their trading relations in favor of China in response to the protectionism of the Trump administration.

Instead of staying focused on stemming the slow but steady decline of their manufacturing sectors at the hands of China, many countries are under such acute short-term pressure from US tariffs that they are willing to ease up on Beijing. Canada even reversed some of its measures by in January agreeing to a trade deal with China. In exchange for better export conditions for Canadian canola, crabs, lobsters and peas, Ottawa will allow up to 49,000 Chinese EVs to be imported tariff-free and has encouraged Chinese EV investment in Canada.

This marked a complete U-turn for the Canadian government, which in 2024 had joined the US in raising major trade barriers for certain Chinese goods, most notably a 100 percent tariff on EVs made in China. The January trade deal was a huge symbolic victory for Beijing and very public display of underlying policy trends in 2025: Countries facing issues with imports from China and issues with exporting to the US are increasingly willing to use China as a hedge against a more assertive US, whose tariff policy poses a greater short-term threat.

Countries showing a faltering commitment to a continued build-up of trade defenses against China – those simultaneously launching new measures and importing more – were both highly industrialized and among the least developed. Advanced countries may have taken the view that their industrial capacities are large and diverse enough to withstand continued attrition from China for a time, while the least industrialized have much less to lose, even if low-cost imports from China may undercut any ambitions to build manufacturing capacity.

A small group of governments introduced significant new barriers

But, aside from the Trump administration, a small group of governments did introduce a significantly higher number of new barriers and investigations in 2025 than their peers. Countries including India, Brazil, Turkey, and Mexico have several things in common: They are rising powers with industrialization plans already underway and have significant regional – and in some cases global – ambitions that weaken the gravitational pull of both the US and China. As a result, they are less constrained in shaping strategies around one or the other.

Some of these countries are in the process of industrializing and have remained committed to raising their trade defenses against China. Their growing industrial bases lack the manufacturing scale and the economic space to absorb sustained price pressure from China. Others have very particular motivations: India faces major geopolitical friction with China over their unresolved border dispute, Brazil and Turkey have ambitions to become major industrial hubs in their own right, Mexico is closely tied to the North American market.

Current trends give China’s leadership valuable breathing space

The underlying slowdown in global trade-defense measures is good news for Beijing as it continues to struggle to unlock more consumption at home to absorb surging industrial production. With China’s export growth in 2025 outpacing trading partners’ attempts to restrain it, the leadership in Beijing very likely views the situation as tolerable – even if it falls far short of the ideal of a world with no trade barriers. Current trends give China’s leadership valuable breathing space in the face of ongoing challenges to the domestic economy.

But Beijing must also factor in that countries in the coming years will likely find ways of managing the short-term impact of US tariffs and once again shift their attention to the long-term challenge posed by China’s industrial overcapacity. While Beijing no doubt views the new precarity of China’s access to the US market with unease, it is surely thanking its lucky stars that Washington’s turn towards broader trade protectionism has changed the calculus of so many other countries in ways that offset Trump’s harder stance – at least for now.