Too little, too late? – Demographic and structural challenges hobble China’s pension system

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

Summary

- From January 2025, China began to raise its very low statutory retirement age – the first adjustment in 70 years. Over the next 15 years, it will gradually rise to 63 years for men and to 55 - 58 years for women.

- China has one of the most rapidly aging populations in the world. Officials and experts have long warned that demographic trends will impact the sustainability of the social security system and economic growth.

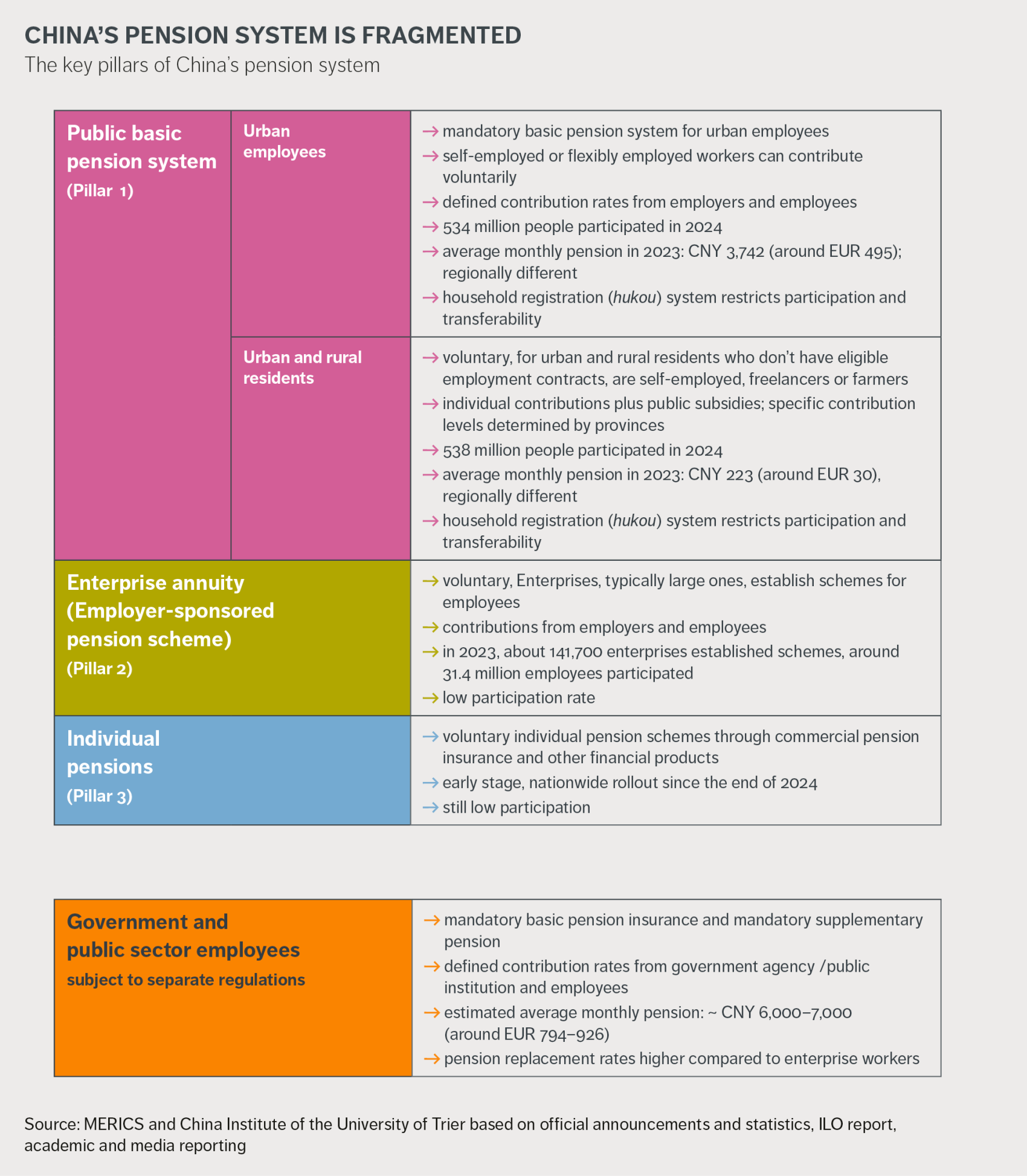

- China’s pension system has come a long way. But lingering structural problems remain, above all, inequalities, sustainability and reach. Wang Xiaoping, Minister of Human Resources and Social Security, has listed improving sustainability to expanding coverage as key tasks.

- Experts point to challenges ahead: solving the looming pension fund gap without hampering the competitiveness of enterprises.

- The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is banking on the spending power of older people for a “silver economy.” An insufficient social security system and lack of buy-in of China’s younger generation may become a risk, not just for consumption but social cohesion.

- Policy language at this year’s National People’s Congress in March and the next five-year plan will be important indicators of political priorities.

After decades of foot-dragging, China adjusts its pension age

From January 2025, China began to raise its very low statutory retirement age – the first adjustment in 70 years. Over the next 15 years, it will gradually rise by three to five years to 63 years for men and to 55 - 58 years for women, depending on their professions. After decades of foot-dragging, the reform package was quickly adopted in September last year. Highlighting its importance, the plan was integrated into the resolution adapted at the Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) last July that spelled out Beijing’s “reform and modernization program” for the next five years.

China has one of the most rapidly aging populations in the world. In 2022, China’s population fell for the first time since the 1960s. In 2024, the country had around 310 million people over 60 – roughly 22 percent of the population. The WHO estimates this figure could rise to 28 percent, or 402 million people by 2040. China’s development has greatly improved life expectancy, but the low birth rate means that a shrinking workforce must support a fast-growing number of retired people.

Officials and experts have long warned that demographic trends will impact the sustainability of the social security system and economic growth. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) already rang alarm bells in 2019 when it projected a potential exhaustion of funds in the basic pension system for employees by 2035. Recent years have kicked off new debates around the coverage of people in informal or flexible employment and the broader issue of stagnating incomes and job insecurity.

Facing new reforms, experts and citizens point to bumps ahead

Recent policy documents and measures show that the CCP is aware of the need for action. An article written by Wang Xiaoping, Minister of Human Resources and Social Security, provides valuable insights into what lies ahead. It was published in December 2024 in Study Times, the flagship journal of the Central Party School where China’s high-level cadres are trained.

While lauding improvements in China’s social security system since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, she lists key reform tasks ahead:

- Supporting sustainability and the stable operation of the system through retirement age reform, improving financing, and making “reasonable adjustments” to benefits

- Expanding the pension system’s second (enterprise annuity system) and third pillars (individual pension scheme)

- Improving market-oriented investment and operation of funds

- Expanding coverage for flexible and new forms of employment and migrant workers

- Cancelling household registration (hukou) restrictions that hinder social security participation at the place of employment

- Improving the supervision of funds and legal framework, including revising the Social Insurance Law

Wang acknowledges that coordinating the various interests of all parties might be difficult but does not provide any specifics as to how these issues can be resolved. Nor does she reveal details on how financial gaps and imbalances can be managed. Her call for the need “to act within our means,” “to start from reality,” and to “guide the people to form reasonable expectations” can be seen as an indication of constraints.

Former top officials and experts detail structural problems and conflicts

Analyses published in a special issue of “China Reform” (中国改革) in July 2024 provide a more complete picture. The magazine belongs to Caixin Media, regarded as one of China’s high-quality media outlets. The contributions by former top officials and experts appeared before the retirement age reform was announced but shed light on some of the underlying structural problems and conflicting goals.

China’s former Minister of Finance and former Chairman of the National Council for Social Security Fund Lou Jiwei says one of the problems of China’s pension system is “the lack of uniformity in local policies and the fragmented management system.” He notes that “China’s practice of hierarchical and decentralized management is unique among comparable countries. Rather than saying it is a Chinese characteristic, it is better to say it is a Chinese shortcoming.”

Lou calls for more national coordination and says China faces a dilemma in improving the sustainability of the basic pension system for employees: “Increasing the contribution rate [which is quite high compared to other countries] will increase the current cost of the enterprises. And reducing the payment replacement rate [which is quite low compared to other countries] will harm the rights and interests of retirees.”

In addition to retirement age reform, Lou says that unifying standards and bundling responsibilities in one authority could make contribution collection more efficient and alleviate some pressure. To ensure long-term sustainability would require more difficult fiscal reform.

Zhou Wenyuan, a scholar from Wuhan University’s Dong Fureng Institute of Economic and Social Development, also analyzed solutions to the “pension payment gap.” Zhou cautions that “many core variables have changed significantly” since the initial CASS report. In light of rapid changes in the population structure, the impact of Covid-19, and gradual adjustments of the pension insurance system, “it would be necessary to combine recent data and latest trends […] to newly calculate the potential future gaps.” According to his calculation, the insurance fund could run out even earlier than 2035.

For him, the system’s “three goals of maintaining long-term high economic growth, balancing fund revenues and expenditures, and improving the level of protection” conflict with each other in an “impossible triangle.” But transferring more state-owned capital into public pension funds and a centralized and more market-oriented funds operation could be a solution.

Zhou Yanli, former Vice Chairman of the China Insurance Regulatory Commission, emphasizes the importance of pension finance and developing China’s private pension scheme, rolled out nationwide at the end of 2024 as a third pillar of the system. Offering more innovative financial products and services and “personalized pension planning” could enhance its role in the solution. But, as Zhou notes, better laws surrounding pension financing are needed to develop a comprehensive regulatory system, market supervision and consumer protection. Also, “the public’s understanding and participation in pension finance instruments need to be improved.”

Zhou Xiaochuan, Vice Chairman of the Boao Forum for Asia, and former Governor of the People's Bank of China says that, in addition to macro studies about the sources, collection and allocation of funds, experts should also consider socio-economic factors on the micro-level, e. g., how policies impact enterprises, how workers view and plan their pensions, and what incentives they need. He argues that sustainability won’t come merely by increasing contribution rates. Delaying retirement has its limits, too, as labor productivity declines for older workers while higher salaries raise costs, making companies less competitive. On an individual level, more transparency and awareness-raising are needed, says Zhou, to better incentivize people to participate in personal pension plans.

“With a fast-aging society and the economic and social transition […] the pension fund gap is put on the young generation”, Zhou says. This highlights an often overlooked aspect, the growing financial and social pressure on young people who have to take care of both their elderly parents and children.

Online discussions show netizens’ worries and concerns

Online debates show the pension system is a top issue for many. While people generally understand the need to raise the retirement age, they are also concerned about its impact. Many young people say they can’t afford to pay into the social security system, while others fear they are paying for today’s retirees while their own retirement age will be raised even further in the future, meaning far fewer benefits for their contributions. Some highlight the huge differences in benefits for civil servants, urban employees, and rural residents.

What these debates show is a lack of trust in the future and questions about fairness and equality. They offer only partial, anecdotal insights into public buy-in, but if too many people opt out due to a lack of means and incentives, it could hamper the government’s plans to expand the second and third pension pillars.

China needs to act swiftly to solve looming pension fund gap

China’s pension system has come a long way. The basic pension insurance now covers one billion people and has adjusted to a changing labor market. But lingering structural problems – above all, inequalities, sustainability and reach – remain. Urgently needed reforms also face a more complex and difficult context, such as a rapidly aging society, economic woes, and increasing budget constraints. The party and state leadership are aware of this and have formulated a list of corresponding policy goals, which remain vague on how to resolve conflicting goals.

Prominent Chinese experts and former policymakers convey the complexity and the need for action. In contrast to official plans and statements, some clearly point out that solutions will involve trade-offs. Even proposed solutions like using market mechanisms to expand pension finance products should be read with caution, considering China’s troubled financial markets.

The CCP is banking on the spending power of older people for a “silver economy.” An insufficient social security system could hinder medical support and care mechanisms for many elderly. Old age poverty could become a risk, not just for consumption but social cohesion. The planned expansion of private pension schemes to supplement low benefits requires public trust and buy-in, especially from young people. Policy language at this year’s National People’s Congress in March and the next five-year plan will be important indicators of political priorities.