Dwindling investments become more concentrated - Chinese FDI in Europe: 2023 Update

Report by Rhodium Group and MERICS

By Agatha Kratz (Rhodium Group), Max J. Zenglein (MERICS), Alexander Brown (MERICS), Gregor Sebastian (Rhodium Group) and Armand Meyer (Rhodium Group)

Building on a long-standing collaboration between Rhodium Group and MERICS, this report summarizes China's investment footprint on the EU-27 and the UK in 2023, analyzing the shifting patterns in China's FDI, as well as policy developments in Europe and China.

Key findings

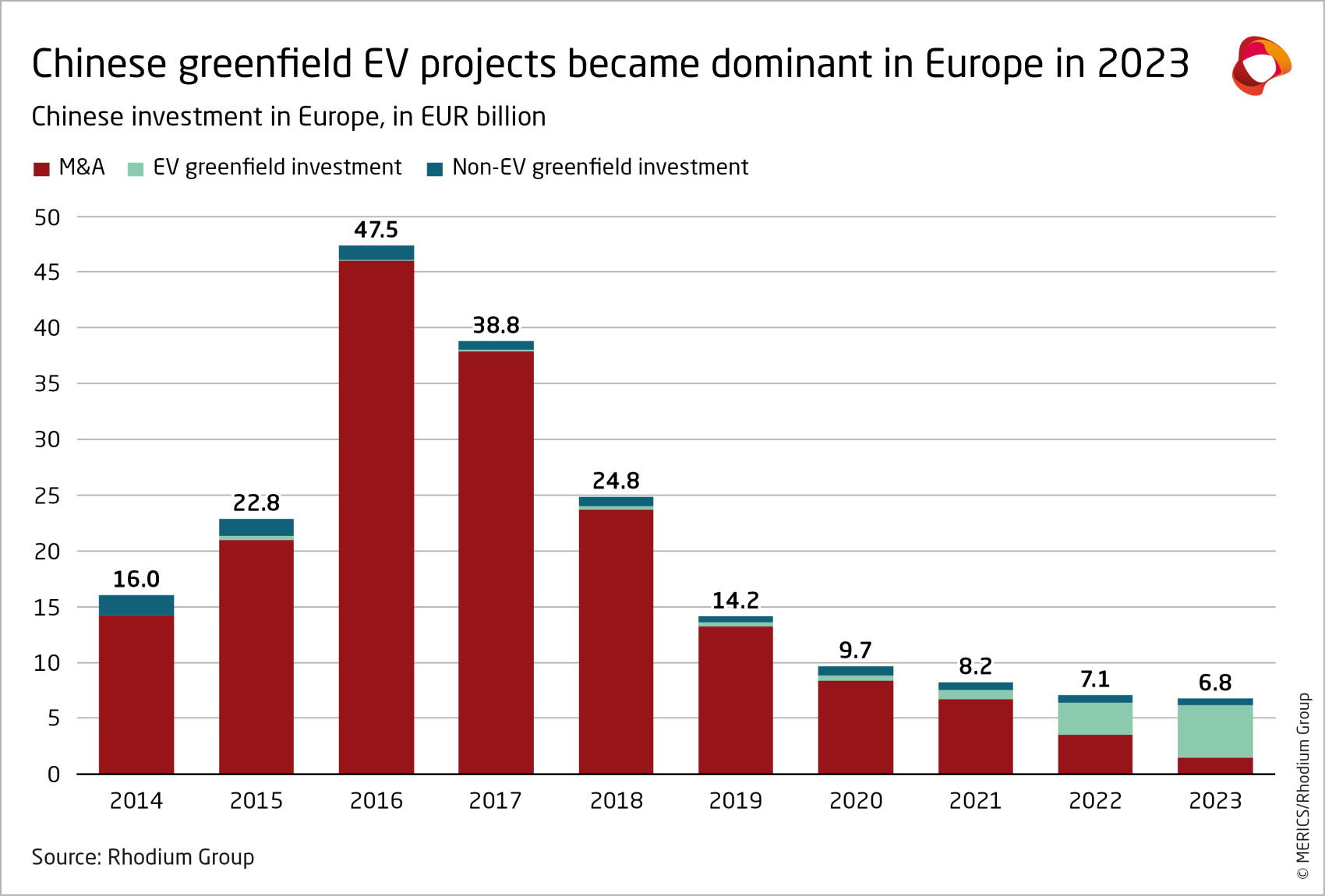

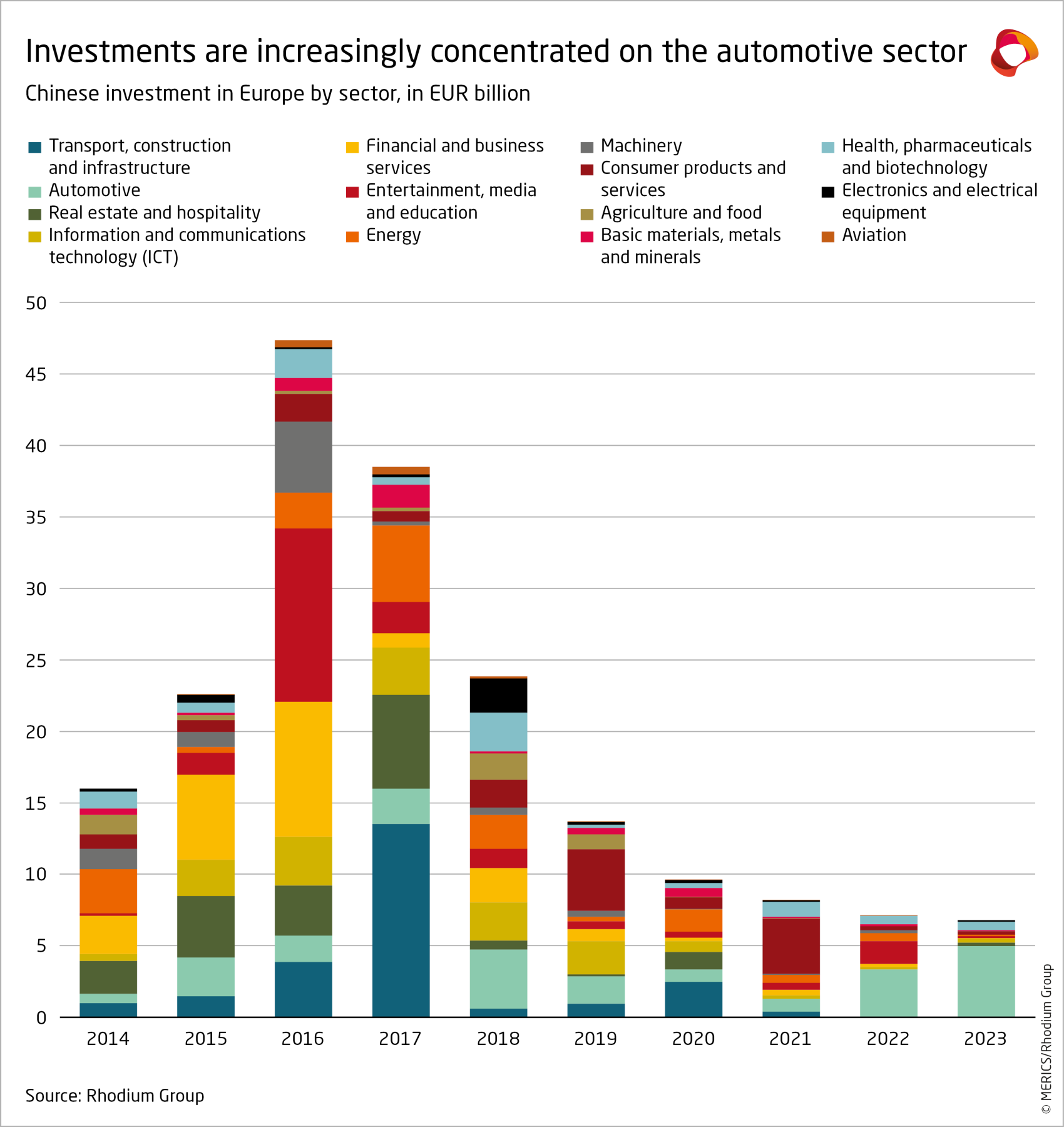

- Chinese investment in Europe drops to lowest level since 2010: Chinese investment in Europe (defined here as the EU-27+UK) slipped again to EUR 6.8 billion in 2023, from EUR 7.1 billion in 2022. This was the lowest level since 2010.

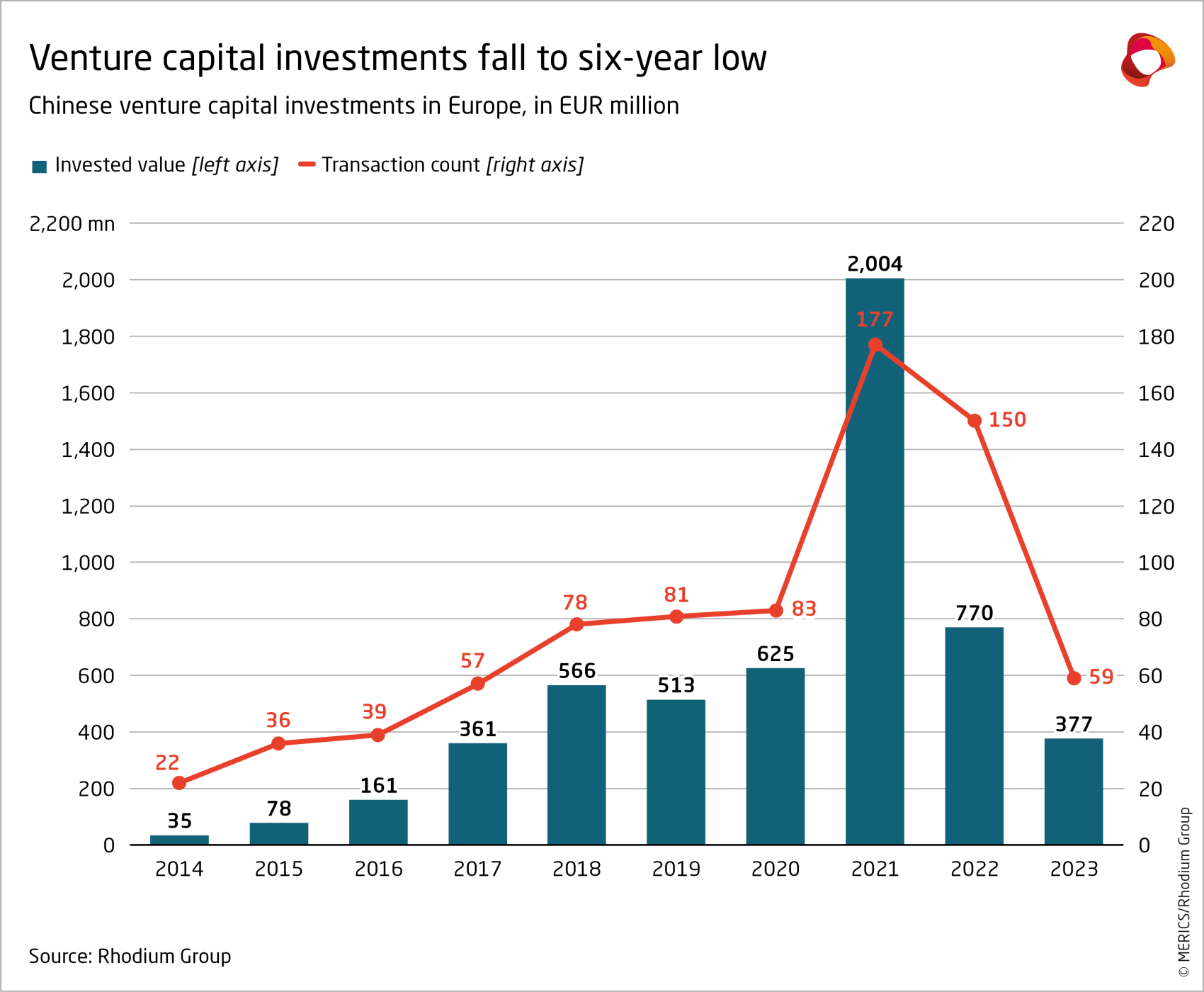

- Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) keep tumbling: The value of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) fell by 58 percent to just EUR 1.5 billion. China’s economic difficulties and strict capital controls, alongside increased scrutiny of foreign investment into Europe, contributed to the fall in M&A deals.

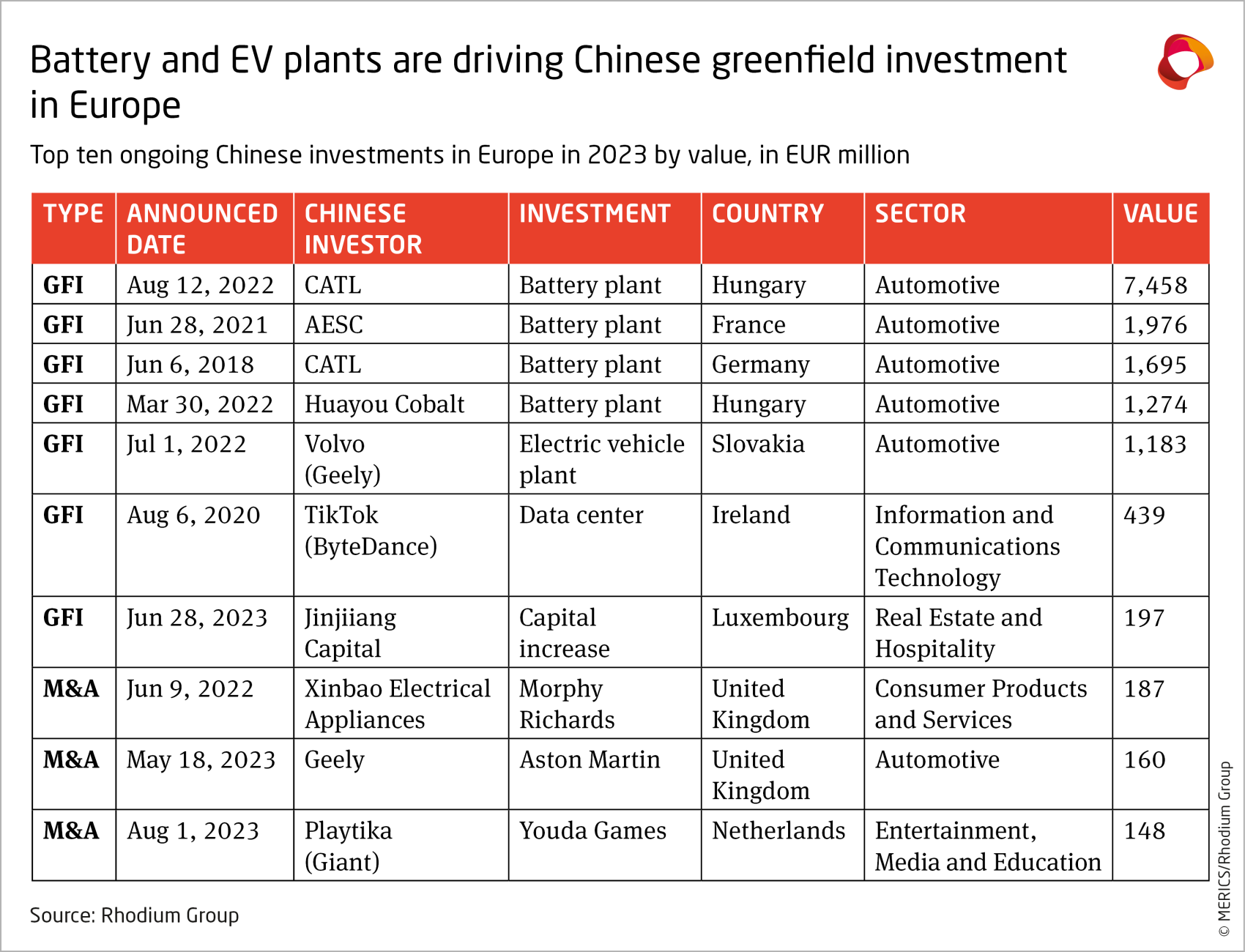

- Greenfield investment keeps FDI levels from falling off a cliff: The share of greenfield investment shot up to 78 percent in 2023, a further increase from 51 percent in 2022. Top greenfield projects in 2023 came from private firms CATL, AESC and Huayou Cobalt, who invested in battery plants in Hungary, Germany and France.

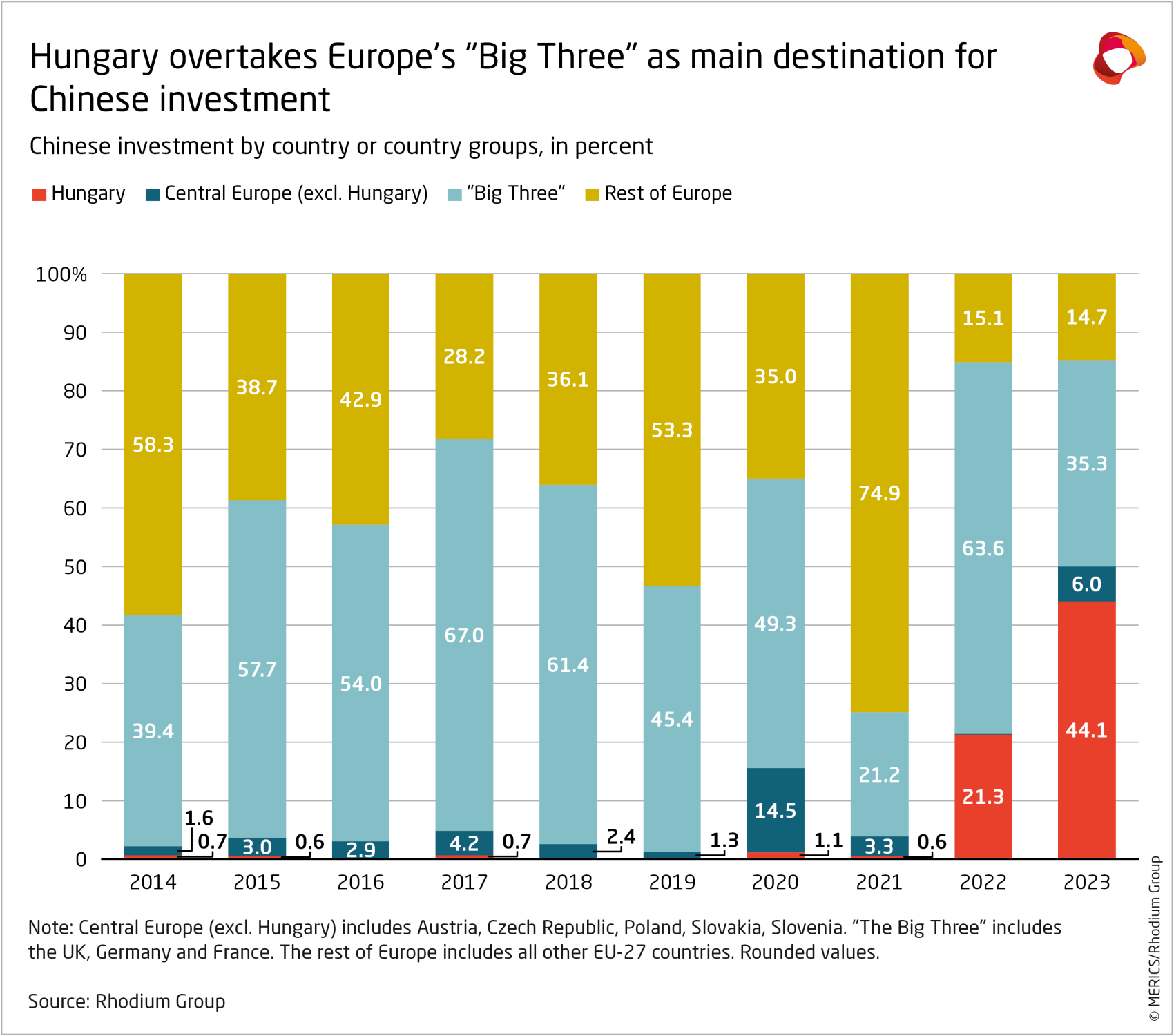

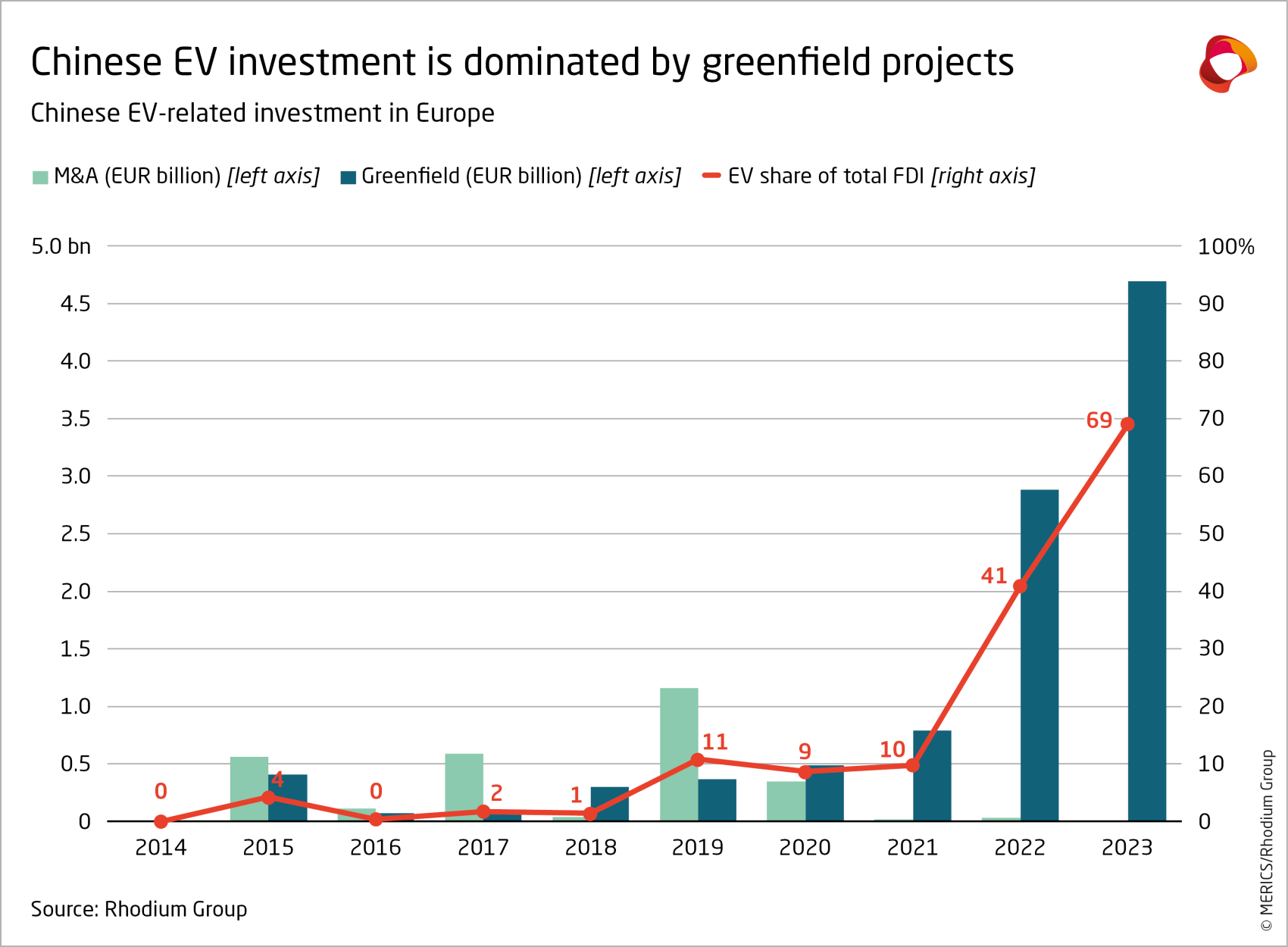

- EV driven investments propel Hungary as the top destination: In 2023, Hungary received 44 percent of all Chinese FDI in Europe, benefitting from the surge in electric vehicle (EV) investments. Over two thirds (69 percent) of Chinese FDI were made in the EV sector in 2023, up from 41 percent in 2022.

- Investment is spreading along the EV supply chain: Chinese FDI is increasingly moving both up- and downstream along the EV value chain. Chinese suppliers of battery inputs like cathodes and anodes have announced two greenfield projects worth over a billion euros each, and which are expected to break ground in 2024. BYD has announced plans to produce EVs in Hungary by 2026.

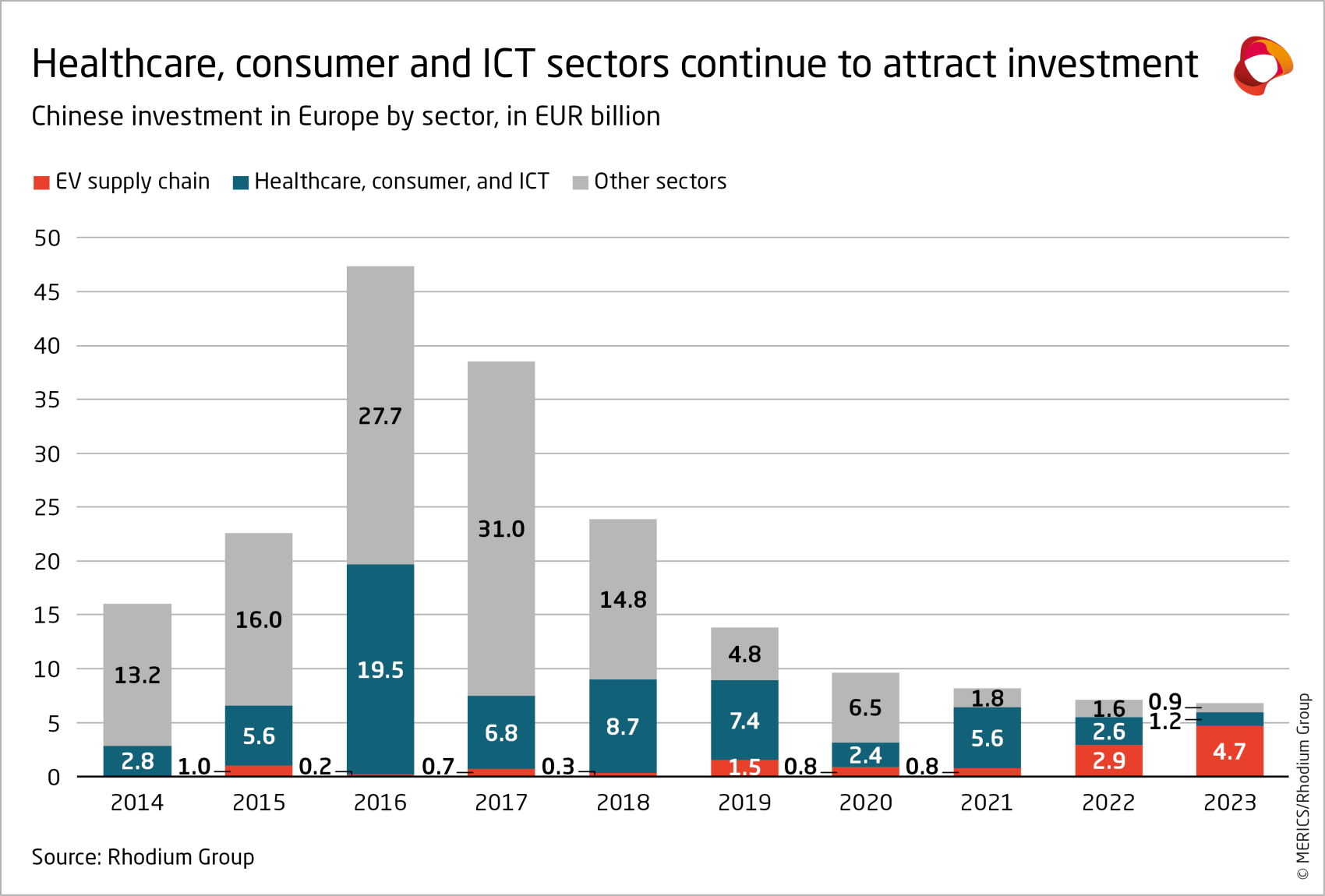

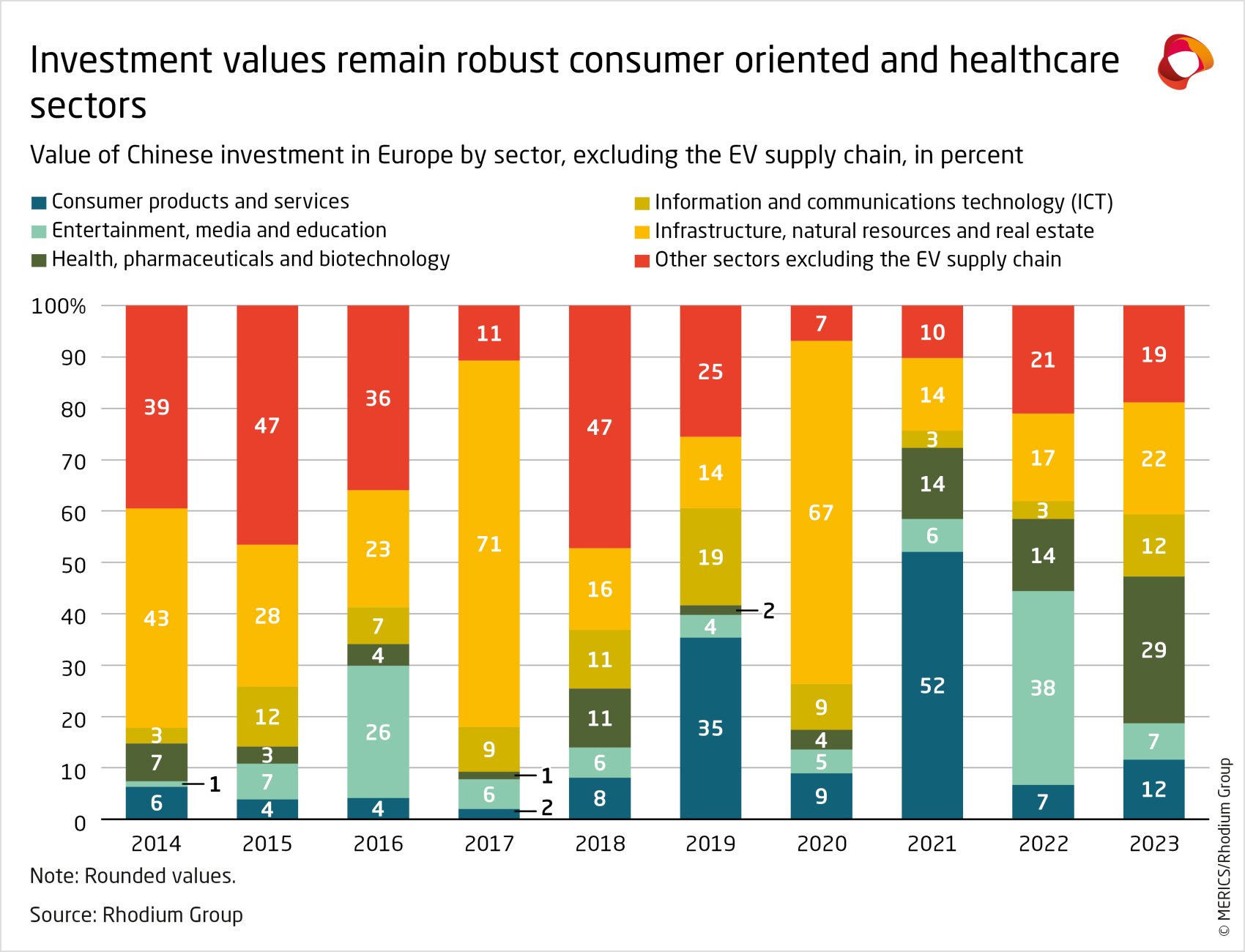

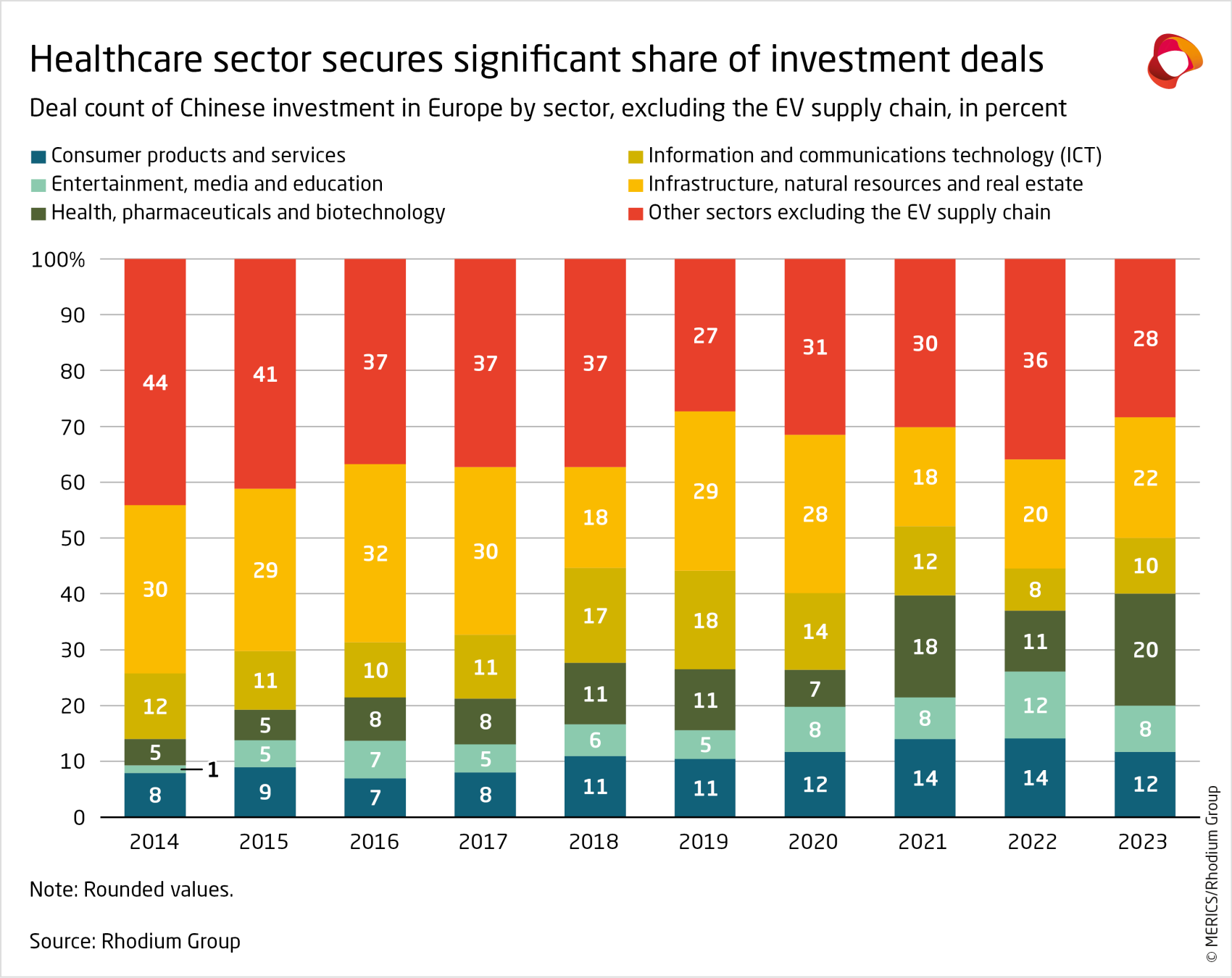

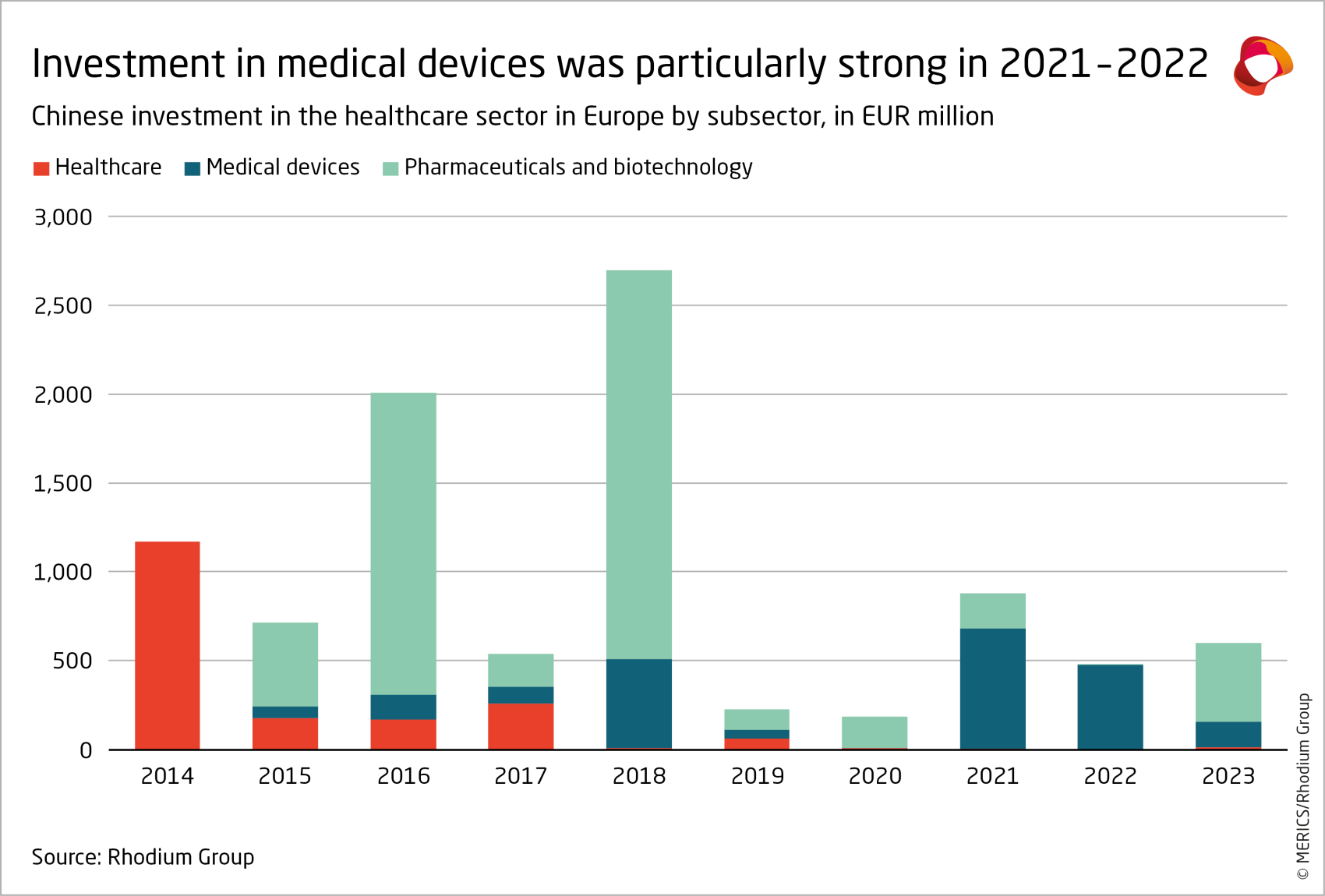

- The healthcare, consumer and ICT sectors remain relatively resilient: Europe’s healthcare, consumer products, entertainment, and information and communication technology (ICT) sectors continue to appeal to Chinese investors. They attracted EUR 3 billion in annual Chinese FDI on average during 2021 – 2023. Medical devices are a key area of interest, accounting for two thirds of investment in the healthcare sector between 2021 – 2023.

- The EU proposes updated screening regulations: The geographical and sectoral scope of investment screening regimes in Europe keeps expanding. The EU is working on greater consistency and a wider remit for screening regulations. Chinese firms looking to invest in strategic sectors in Europe can expect to be the target of more regulatory scrutiny.

- No significant recovery in sight: The drop in Chinese investment in Europe will continue to be cushioned by ongoing investment in the EV sector. But a substantial uptick is not expected. Instead, investment is likely to remain at low levels due to the weak financial positions of Chinese firms and increased government oversight in Europe. Chinese firms must also weigh up market opportunities in Europe against the backdrop of growing EU-China trade tensions.

1. Chinese investment in Europe stabilizes at low levels in 2023

Chinese corporate investors faced challenges and uncertainties in 2023 from a mix of political and economic factors in Europe and globally. Uncertainty about the global economy impacted the investment environment for Chinese firms, amid rising geopolitical tensions that include the protracted war in Ukraine and new conflict in the Middle East. China’s lackluster growth in the post-Covid period has weakened the financial footing of many Chinese firms.

Strict capital controls and the depreciation of the Chinese yuan (CNY) also disincentivized outbound investment. The European Union (EU) is seeking to recalibrate the EU-China relationship and strike a balance between de-risking and cooperation, a shift that has stoked the uncertainties facing potential Chinese investors. This all happened amidst enhanced oversight of foreign investment as economic security has risen up the agendas of European governments.

Many of these factors have been present for several years, contributing to the steady decrease in investment flowing from China into Europe. In 2023, Chinese investment in the EU and the UK (hereafter referred to collectively as “Europe”) slipped further, though only marginally, from EUR 7.1 billion in 2022 to EUR 6.8 billion.1 This was the lowest level of investment seen since 2010. At the same time, an uptick in newly announced greenfield investments suggests that the precipitous decline in Chinese investment since 2016 may be levelling off, as investment in the electric vehicle (EV) sector continues.

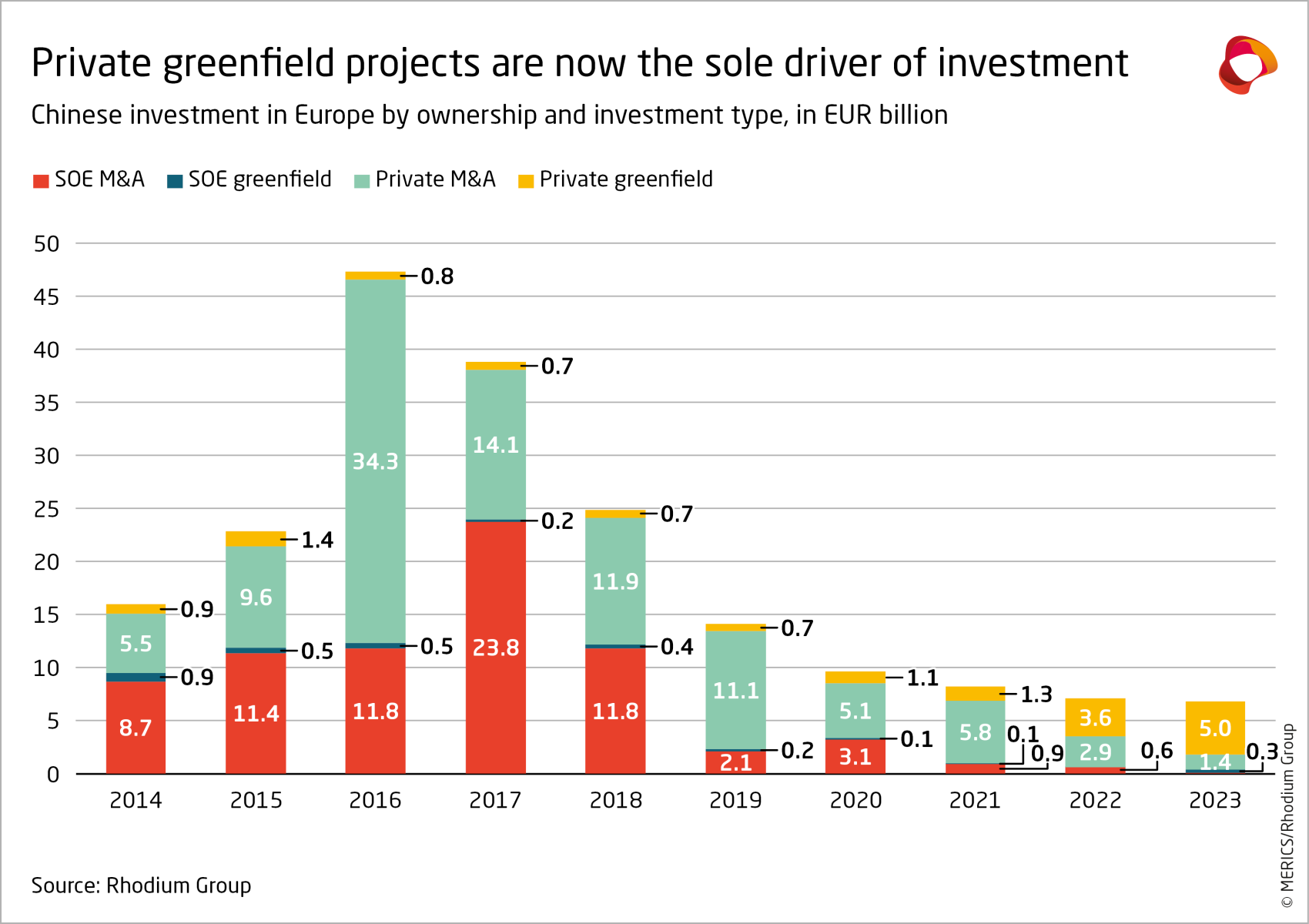

1.1 Greenfield investment keeps chinese FDI levels afloat

The make-up of Chinese investment in Europe is undergoing a fundamental shift as greenfield projects are becoming the dominant form of investment. The share of greenfield investment (GFI) has increased from a mere two percent in 2017 and an average of nine percent between 2012 and 2021, to 51 percent in 2022 and as high as 78 percent in 2023.

A series of multi-billion-euro investments in battery and EV plants across Europe pushed Chinese greenfield investment to EUR 5.3 billion in 2023, up 48 percent on 2022.2 By contrast, the value of M&A investments declined again in 2023, by 58 percent, to only EUR 1.48 billion – their lowest value since the global financial crisis in 2009. This was the result of fewer acquisitions overall, smaller average deal size and the absence of billion-euro M&A deals.

Major deals had a big impact on the aggregate figures in recent years, including Hillhouse Capital’s acquisition of Philip’s household appliances business for EUR 3.7 billion in 2021, and Tencent’s acquisition of British video game maker Sumo Digital for EUR 1.3 billion in 2022. In 2023, no single deal exceeded EUR 200 million – compared to seven in 2022, and five in 2021.

The main causes of this continued decline likely include economic headwinds and strict capital controls within China, alongside increased scrutiny of Chinese investments in Europe. Weak global economic growth and rising geopolitical tensions may also have dampened the appetite of Chinese investors for overseas investment.

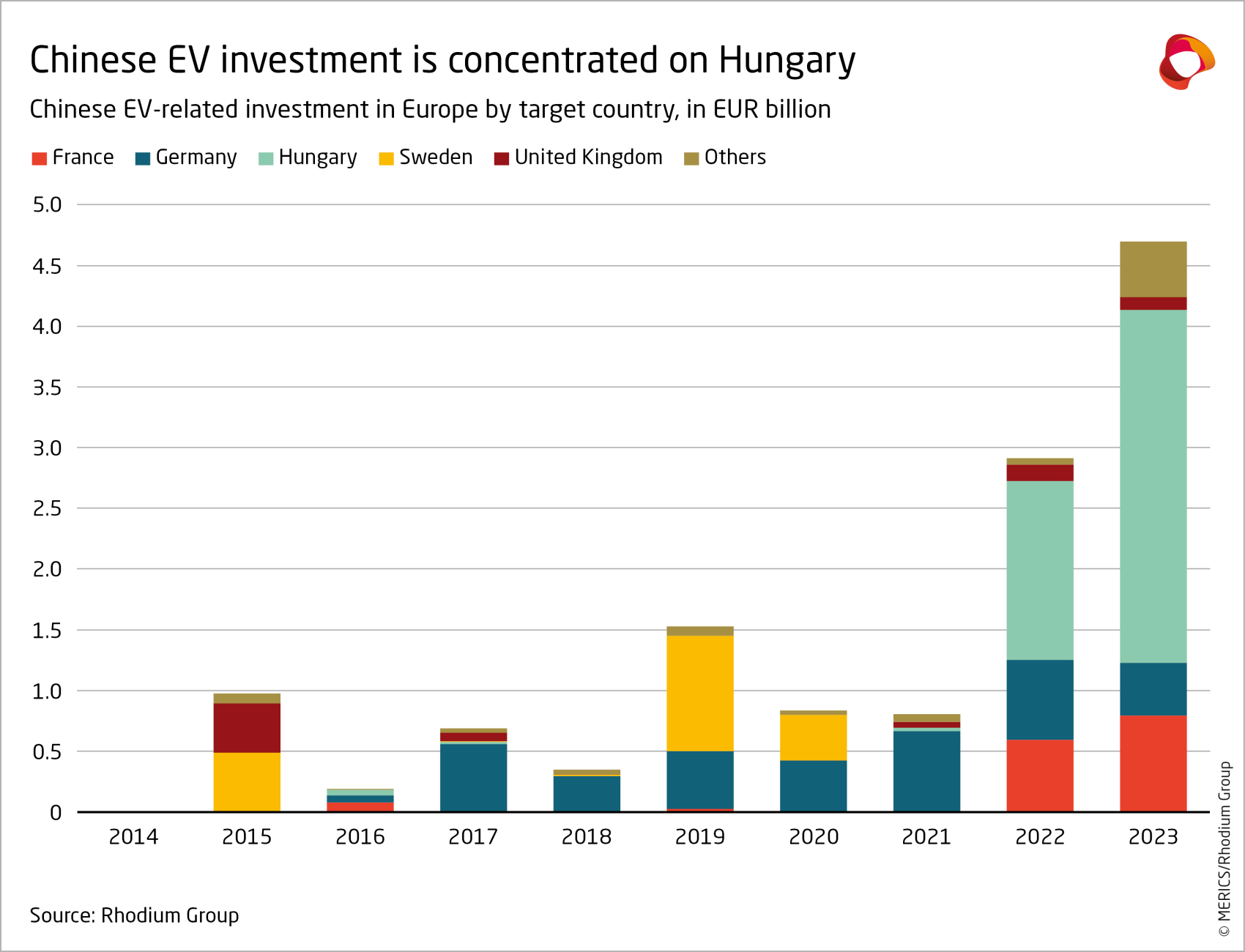

1.2 Hungary snatches top spot due to EV-related investment

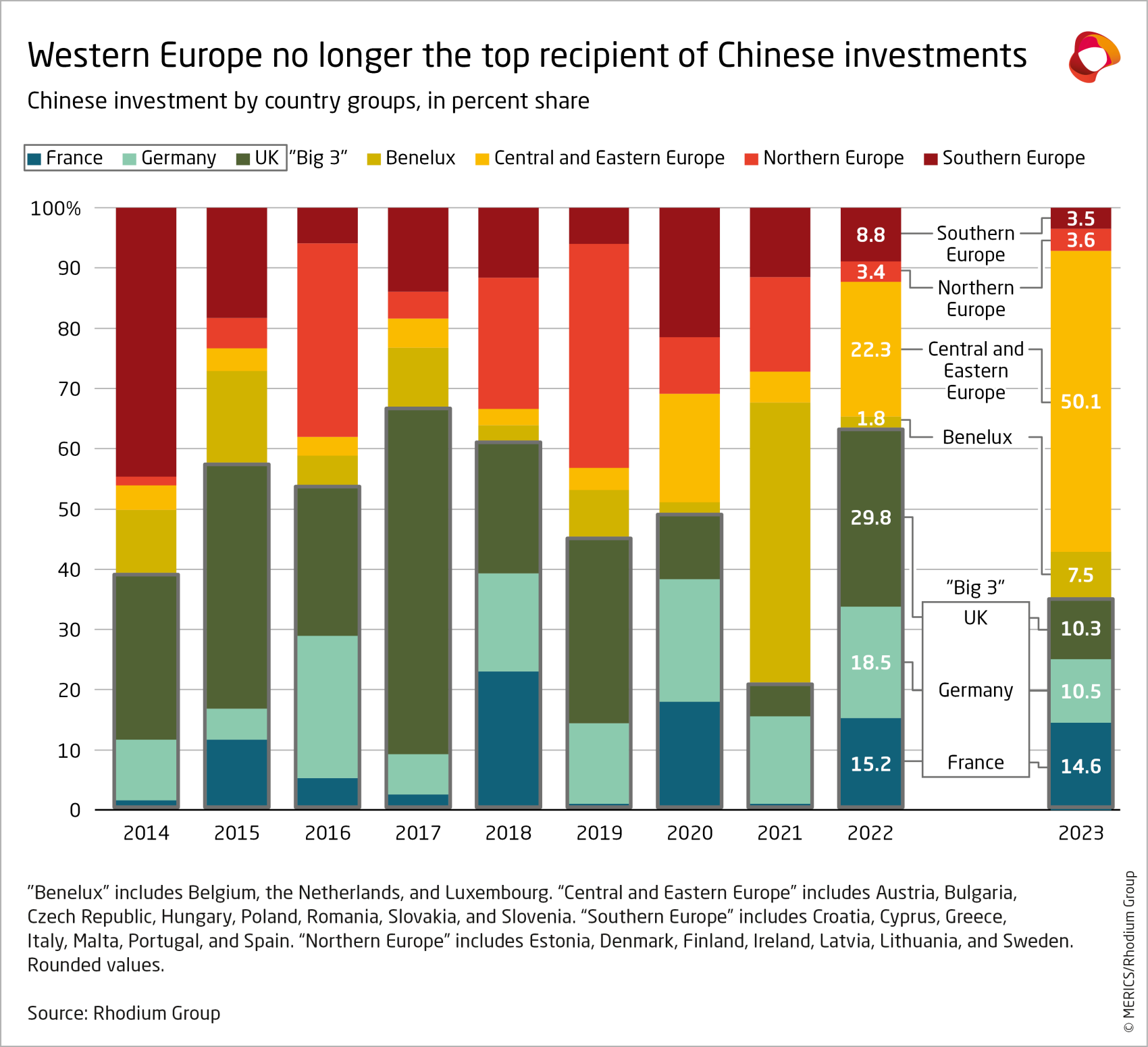

Large scale battery and EV investments have led to a dramatic shift in the regional distribution of Chinese investment in Europe, turning Hungary into their primary beneficiary. Investment in the country has skyrocketed in the last two years, up from a very low base.

Between 2012 – 2021, average annual investment into Hungary was just EUR 89 million. In 2022, it rose to EUR 1.51 billion, and reached EUR 2.99 billion in 2023. The steep rise was due to large-scale investments in battery plants built by CATL and Huayou Cobalt.

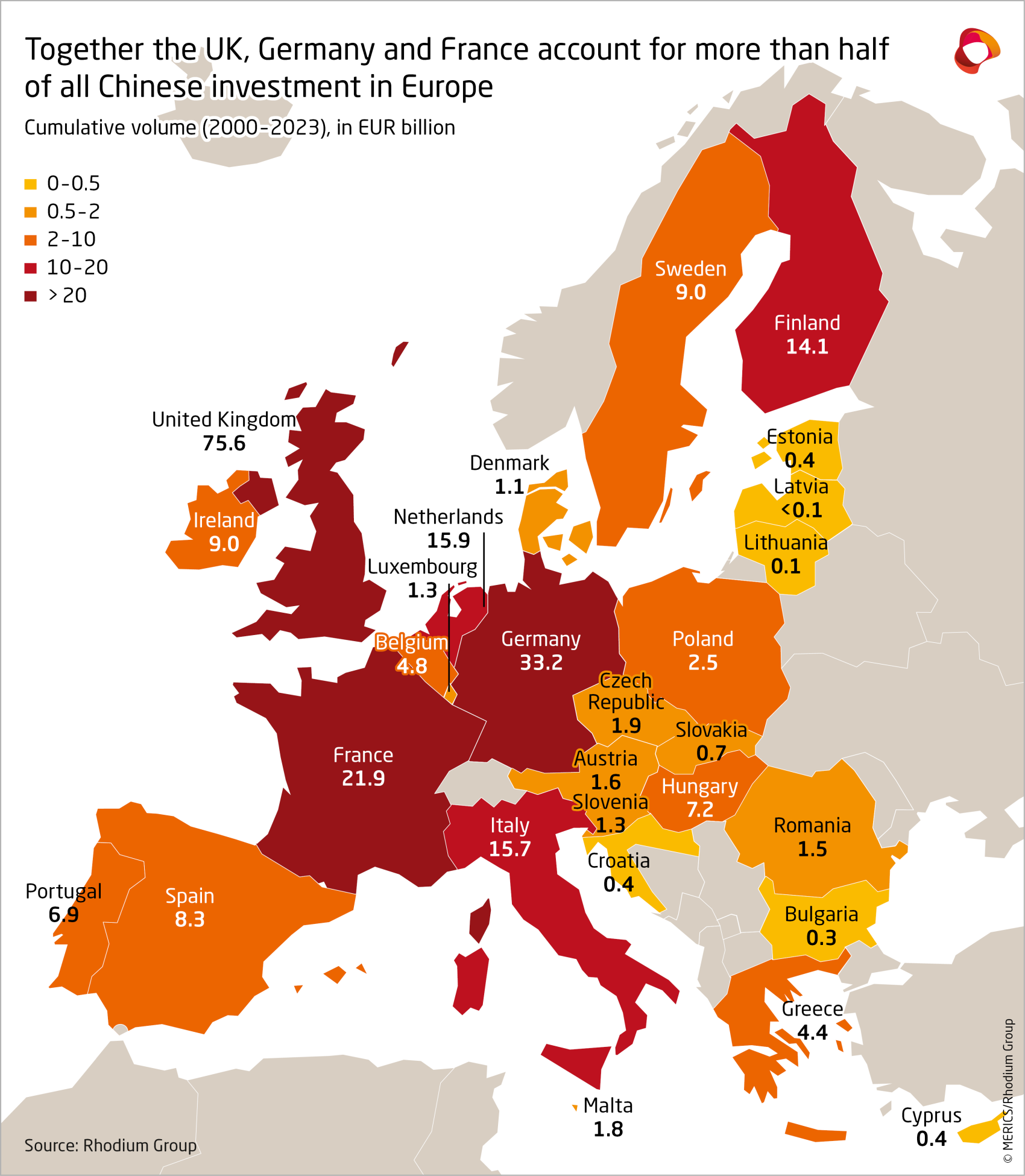

As a result, Central Europe has become the most important destination for Chinese investment. Hungary alone captured 44 percent of all Chinese FDI into Europe, or more than the “Big Three” – France, Germany and the UK – combined. Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia also received some investment in 2023. The latter received EUR 364 million in Chinese FDI, with major investments including Volvo’s (majority owned by Chinese firm Geely) EV battery plant and Gotion High-Tech’s acquisition of a 25 percent stake in Inobat.3

By contrast, the share of investment going to the “Big Three” countries declined to 35 percent in 2023, compared to an average share of 53 percent between 2013 – 2022. In value terms, investment in the “Big Three” fell by 47 percent between 2022 and 2023, from EUR 4.5 billion to EUR 2.4 billion. Despite this decline in investment flow, these countries still account for more than half (54 percent) of all cumulative Chinese investment in Europe since 2000.

In comparison, countries beyond Hungary and the “Big Three” received very little investment from Chinese firms. While these other countries attracted about half (48 percent) of Chinese investment on average between 2012 and 2021, in 2022 and 2023 this share amounted to just 15 and 20 percent respectively.

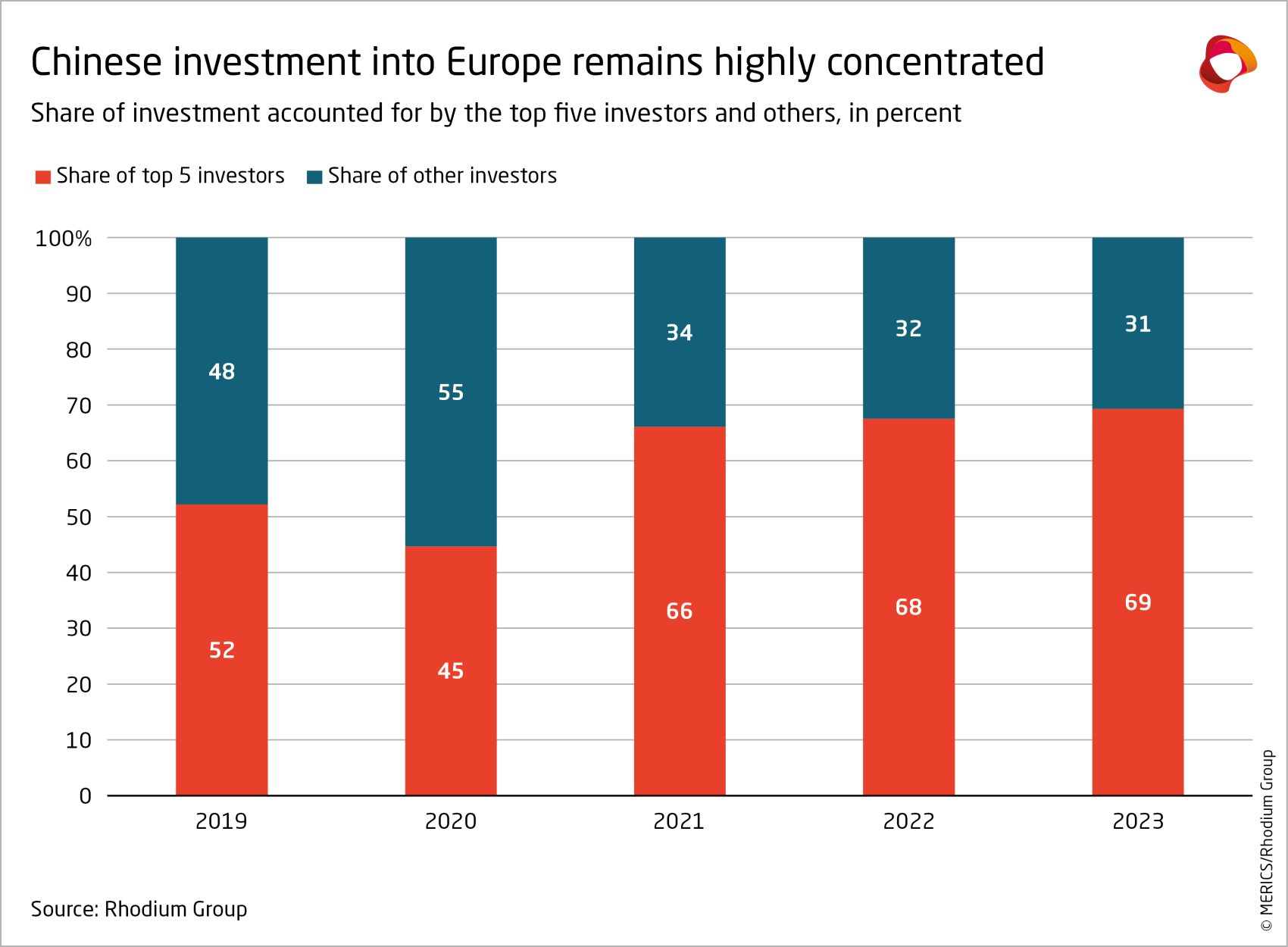

1.3 Chinese investment remains heavily concentrated

As overall investment levels have come down, the relative importance of individual deals and investors has increased. The top five Chinese investors consistently made up two thirds of all Chinese investment into Europe between 2021 and 2023, compared to 45 percent in 2020. Private firms engaging in greenfield projects or major acquisitions were the driving force behind this high level of concentration, particularly CATL’s battery plant projects in Hungary and Germany in 2023 and 2022, as well as Hillhouse Capital’s acquisition of the Philip’s household appliances business segment in 2021.

In 2023, the top four investors were all active in the EV or battery industries, and together accounted for 66 percent of total investment – also a side-effect of the sharp drop in major deals in other sectors.

1.4 EV supply chain investment is more dominant than ever

The past two years have seen a significant surge in Chinese investment in the EV value chain in Europe. In 2023, Chinese EV-related investment amounted to EUR 4.7 billion, or about 70 percent of total Chinese FDI in the EU, which was another sharp increase (up 61 percent) on the previous year’s EUR 2.9 billion.

As in 2022, the bulk of that investment came from a handful of billion-euro investment in battery plants. Leading Chinese battery manufacturers CATL, AESC and Svolt contributed 85 percent of the total EV-related investments.4 CATL has established a battery plant in Germany and is currently constructing a EUR 7.3 billion battery plant in Debrecen, Hungary. AESC is investing in plants in Douai, France, worth EUR 2 billion and in Sunderland, UK, worth EUR 1.3 billion.

The trend is likely to continue. AESC announced a further project in Spain worth EUR 2.5 billion that is expected to break ground in 2024. Svolt is planning to build two battery projects in Germany but has run into local opposition. Finally, Eve Energy has announced a battery investment worth EUR 1 billion in Hungary.

Chinese FDI is increasingly moving both up- and downstream along the EV value chain. Chinese suppliers of battery inputs like cathodes and anodes – leaders in their respective part of the battery supply chain – are trying to expand their market share in Europe’s rapidly growing battery ecosystem. CATL-supplier Semcorp commenced operations of its EUR 340 million lithium-ion separator factory in Hungary in 2023. Two Chinese firms, Putailai and Shanshan, unveiled significant investments in Sweden and Finland, worth EUR 1.5 billion and EUR 1.3 billion respectively, which focus on anode material production. These are likely to break ground in 2024.

There are also signs that Europe could soon see more downstream investments in EV production. In Slovakia, Geely-owned Volvo is already constructing an EV plant with a price tag of EUR 1.2 billion. In December 2023, China’s leading EV-maker BYD announced plans to produce EVs in Hungary by 2026. The value of BYD’s investment has not yet been disclosed, but construction kicked off in early 2024. In April 2024, Chery and Spain’s Ebro EV Motors announced plans to invest EUR 400 million to jointly produce cars in Barcelona. The EU’s ongoing probe into Chinese EV imports could incentivize further investments by Chinese EV producers to avoid potential duties on imports.

Geographically, China’s EV-related greenfield FDI remains heavily concentrated, with Hungary, France, and Germany collectively absorbing 88 percent of all EV-related investment. In 2023, even more than in 2022, Hungary was a clear frontrunner. The new greenfield investments from BYD, in addition to investments from Semcorp, CATL and Huayou Cobalt mean Hungary is likely to stay among the top recipients of Chinese FDI in the coming years. France and Germany, for their part, attracted EUR 790 million and EUR 438 million in EV-related investment respectively.5 Battery investments in these countries are linked to supply contracts with local carmakers: AESC in Douai supplies Renault, while CATL in Debrecen serves BMW and Mercedes in Germany and Hungary.

Chinese firms might feel that their investment is safer in a country like Hungary that has close ties to Beijing than in other destinations, like Italy, that have recently increased regulatory scrutiny over corporate governance at Chinese companies. But Hungary’s top position in attracting EV investment is not limited to Chinese companies – and hence not just a geopolitical feat. South Korean firms, too, have increased their FDI footprint in Hungary – likely because the country hosts several leading carmakers, offers cheap and skilled labor, doles out millions of euros in subsidies, and has promised to build infrastructure and industrial parks around the investments.

China’s EV investment is not limited to Europe. Battery and EV producers have also announced huge investments in Asia, Latin America and North Africa. Many of these investments are fueled by local content requirements in host countries and, crucially, the US Inflation Reduction Act that requires certain raw materials to be processed in the United States or its free trade partners.

In Europe’s immediate neighborhood, Chinese companies have announced major EV-related investments, including by Gotion High-Tech and CNGR in Morocco. Its large reserves of phosphate, a key component in lithium-iron phosphate batteries, make Morocco an attractive destination for Chinese EV investors. The kingdom also boasts a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the United States and the EU and hosts several French carmakers’ plants, which are intended for shipping into the European market. Morocco would become an even more attractive manufacturing hub if the EU decides to impose duties on China-made EVs.

3. Europe moves to tighten investment screening

3.1 Share of screening cases involving Chinese investments falls

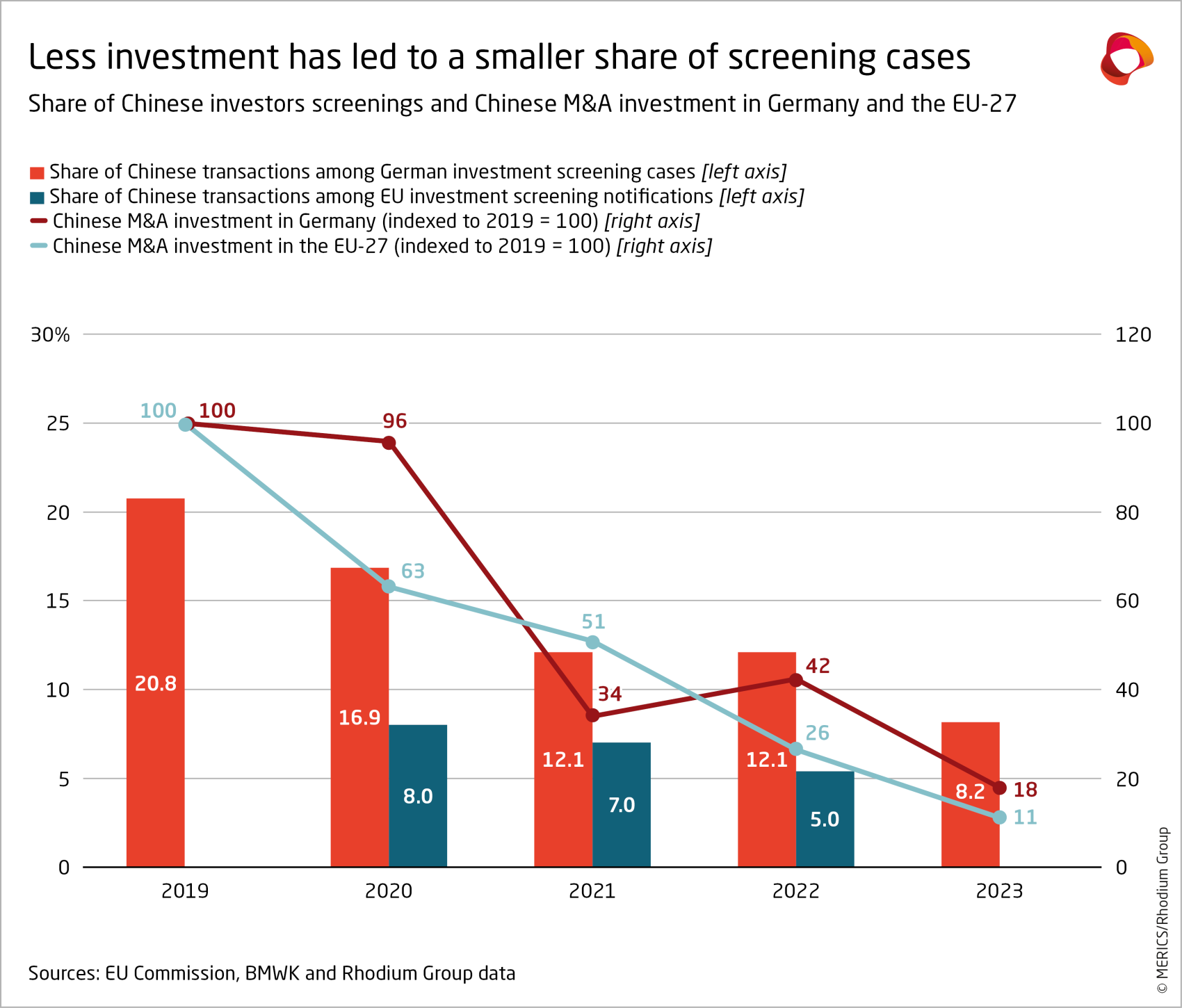

The proportion of transactions reviewed by screening authorities in Europe related to Chinese firms has been on the decline in recent years, roughly tracking the fall of Chinese FDI in Europe. The share of investment screening notifications submitted to the European Commission, where the ultimate shareholder originated in China, declined from 8 percent in 2020 to 5 percent in 2022 (the last year for which data is available).6

The data for Germany reflects a similar trend, with the share of screened investments where the acquirer is a Chinese firm falling from 17 percent in 2020 to 12 percent in 2022 and just 8 percent in 2023.7 Lower levels of investment from China have likely contributed to this reduced share. Another possible reason is that Chinese firms have become more wary of acquiring firms from certain European countries, or in certain more sensitive sectors, due to increased regulatory oversight.

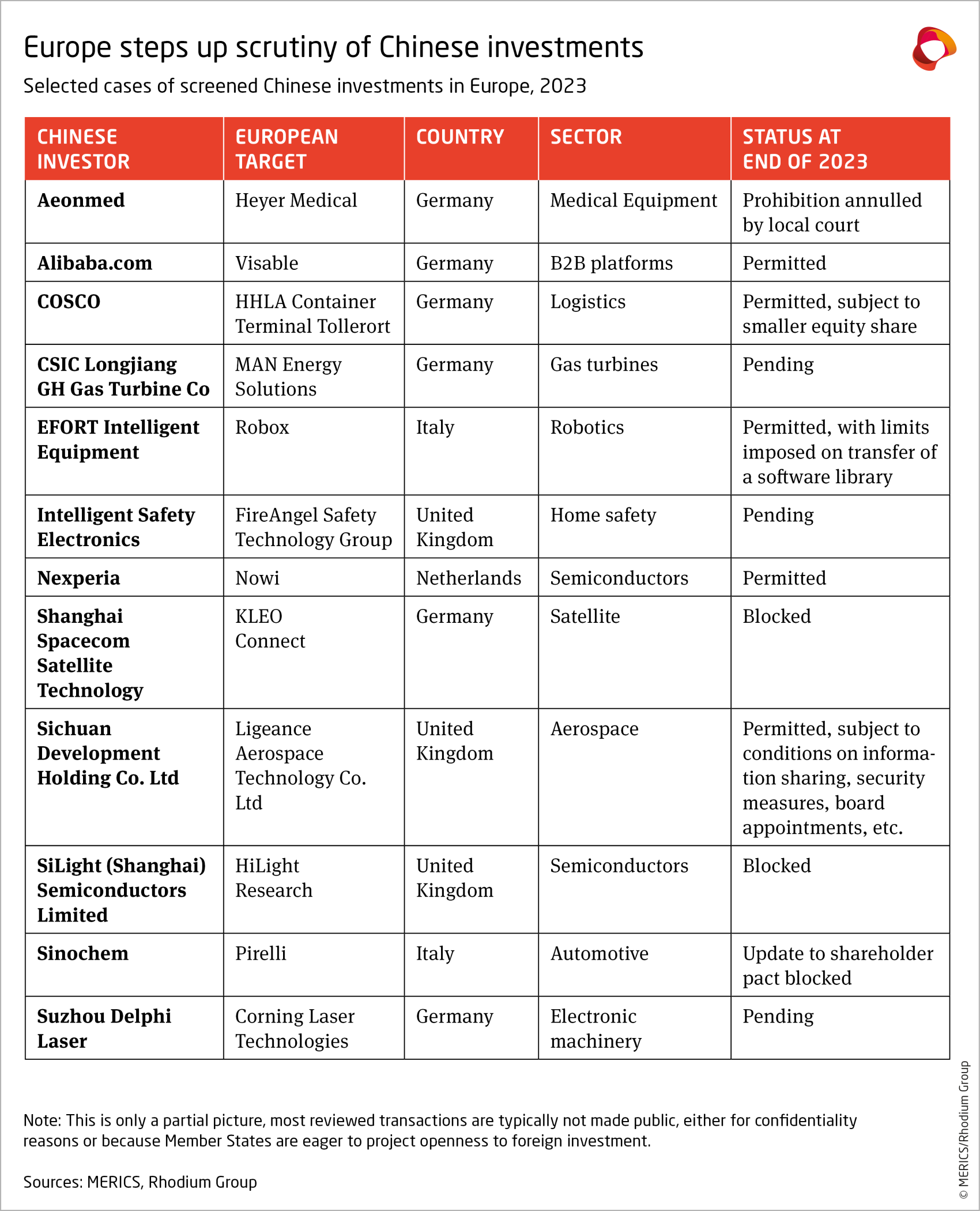

The details of individual investment screening cases are rarely released to the public. Ongoing investigations may be confidential or sensitive. Governments are also wary of damaging their reputation as an attractive destination for foreign investment. We could only identify 12 publicly-reported cases where an investment screening review was launched, or where a decision was made in 2023 (many more have likely taken place).

Five deals were in strategic sectors, such as semiconductors, aerospace, gas turbines, and satellite technology, where national security considerations were likely a key consideration for home governments. Two of these deals were blocked, two were permitted and one decision is still pending (on the acquisition of the gas turbine business of MAN Energy Solutions by CSIC Longjiang GH Gas Turbine).

In addition, the Italian government exercised its authority under the “Golden Power Procedure” rules to intervene in the updated shareholder agreement between tire manufacturer Pirelli and its largest shareholder, China’s Sinochem, to ensure Pirelli’s independence.8

3.2 European commission proposes updates to screening regulations

EU efforts to encourage member states to adopt investment screening measures have already brought significant results. Of the EU’s 27 member states, 24 had passed legislation by April 2024 enabling them to conduct investment screening (double the total number in 2017).9 Only Greece, Croatia, and Cyprus still lack an investment screening regime, though Cyprus is expected to introduce one in 2024.

Six countries either introduced new regimes or updated existing ones between January 2023 and April 2024. The most notable changes were in Belgium and Estonia, where investment screening mechanisms came into force. Ireland signed the “Screening of Third Country Transactions Act 2023”, which is expected to come into force by mid-2024.10 Bulgaria’s parliament amended the Investment Promotion Act in February 2024 to screen FDI for national security or public order concerns.

In January 2024, the EU put forward a proposal to further harmonize investment screening regimes across member states.11 The initiative would entail revisions to the EU FDI Screening Regulation, such that:

- all EU countries must to adopt an FDI screening regime;

- the screening process must be applied to all indirect acquisitions by foreign investors (i.e., EU-based entities controlled by a foreign shareholder);

- investment screening would become mandatory in some areas, for instance for investments in EU-backed projects or programs; critical infrastructure; critical technology and dual-use items, or the supply of critical inputs;

- member states would be encouraged to include greenfield investments in their screening mechanisms

Any updates to the screening regulation are unlikely to come into force before 202612, given the pause for European elections in June 2024 and the EU’s lengthy legislative process. Even then, a transition period would mean changes could not take full effect until 2027. But the eventual impact of the proposed measures would be to increase scrutiny of investments in strategic areas and to strengthen efforts to identify the ultimate shareholders of companies. Chinese investors will need to anticipate a more rigorous regulatory environment as European governments become more cautious and expand their oversight. The hurdles for Chinese investment will get higher, particularly in sectors deemed strategic or sensitive.

4. Outlook

Lower levels of Chinese FDI have become the new normal. This would remain true even if one or two large scale transactions in 2024 were to produce a jump in the value of Chinese investment in Europe. The ability of big, single deals to jolt the picture itself reflects the overall trend for lower FDI. In 2023, there was a dearth of multi-billion-euro transactions, apart from several ongoing EV-related greenfield investments, which have put a floor on annual aggregate investment values.

Yet the new normal has arrived and is likely to persist. This year, the EU and US elections will give investors added reasons to wait and see. Longer term factors that reinforce the trend include the greater focus on economic security, trade fictions (which could escalate) and uncertainty about the strength of China’s economy.

On the one hand, key motivations which could drive further Chinese investment in Europe include:

- Jumping the fence: Escalating trade tensions between China and Europe could compel some Chinese firms in the EV and broader green tech sector to onshore more of their production into the EU to avoid rising tariffs or new defensive duties. Doing so would also align them better with Europe’s de-risking policies and associated incentives (including the Net-Zero Industry Act proposal of 2023, the Critical Raw Materials Act, adopted in early 2024, and data security regulations).

- Seeking greener pastures: China’s slowing and increasingly crowded domestic markets could further incentivize firms to internationalize by setting up operations in Europe.

- Following the battery leader: After a string of large-scale battery investments in recent years, Chinese firms in both the upstream and downstream EV segments have announced additional greenfield projects. These will begin to break ground in 2024, supplementing the already robust level of multi-year investments in the automotive sector.

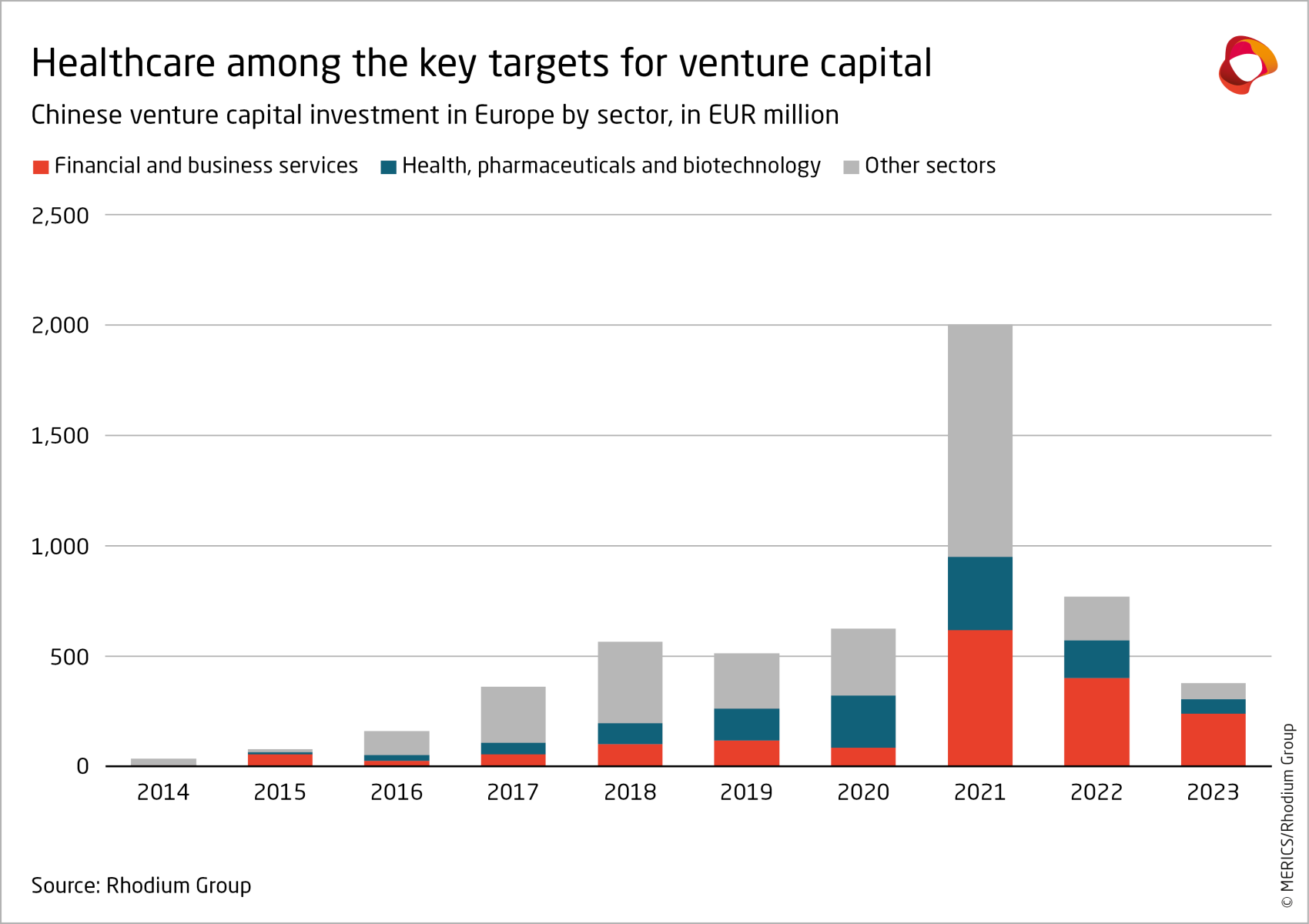

- Targeted technology acquisitions: Europe’s innovation and technology leadership across a range of industrial and emerging sectors will continue to pull in investment interest from Chinese firms, particularly in healthcare and ICT. Even if economic circumstances in China put greater financial strain on firms, small scale investments in these industries are likely to continue.

On the other hand, there is also a long list of constraining factors:

- Weak financial position of Chinese companies: China’s systemic economic challenges, including the indebted real estate sector, high youth unemployment, and low consumer confidence will continue to suppress domestic consumption and weaken the financial footing of Chinese firms. Despite strong investment levels in many manufacturing sectors (including green tech), intense competitive pressures mean many Chinese firms are facing reduced profit margins that limit their capacity for overseas investment.

- Home market priority: Maintaining economic growth and strengthening the local industrial base remains China’s top economic priority in 2024. Amidst a severe downturn in foreign investment, Beijing has released policies to rebuild investor confidence. Some Chinese firms may therefore be wary of announcing major investments abroad.

- Pressure to keep technology at home: Leaders in Beijing might start considering tighter controls on intellectual property (IP) exports to avoid excessive transfers of Chinese IP and know-how to third market competitors, including European ones.13

- EU policy direction on EVs remains unclear: Uncertainty over the EU’s EV market potential, with EV adoption targets facing increased pushback, could cause some companies to hold back major investment decisions, at least until after the EU elections in 2024 or the review of the EU road transport decarbonization policy in 2026.

- Expanded oversight in the EU: Chinese firms will have to contend with persistent scrutiny of Chinese investment across a range of sensitive sectors. Scrutiny could expand to include biotech and healthcare, in addition to more traditional dual-use sectors like semiconductors. The proposal from European Commission Vice-President Margrethe Vestager to apply “trustworthiness” standards to suppliers of key technologies might also constrain market opportunities for some Chinese firms in future. The standards would integrate environmental footprint, labor rights, cybersecurity and data security.

- Strengthened competition policy: In the early months of 2024, the European Commission launched several investigations into bids for public tenders, and general European activities, of Chinese firms based on the Foreign Subsidies Regulation. The cases involve Chinese suppliers of trains, solar panels, wind turbines and security equipment for ports and airports. Together with the first activation of the International Procurement Instrument, these measures create more uncertainty for Chinese firms over their access to the European market and will make investment opportunities less attractive.

- Endnotes

-

1 | The figures presented in this report are based on publicly disclosed investments and provide a conserva- tive estimate of investment trends.

2 | The investment value for such large multi-year greenfield investments is estimated on a quarterly basis and covers the period from when a project breaks ground until the start of production.

3 | No deal value was disclosed for the investment by Gotion High-Tech in Inobat. The EUR 364 million in investment recorded for Slovakia is all attributed to the Volvo EV battery plant.

4 | AESC is headquartered in Japan, but it has been majority owned by Chinese firm Envision since 2018.

5 | Investment in Germany is higher than this recorded figure. The value for Gotion High-Tech’s brownfield investment in a Bosch factory in Göttingen to produce batteries has not been disclosed, and thus could not be accounted for.

6 | Investment screening notifications submitted to the European Commission do not account for all invest- ment screening cases conducted by EU Member States. While Article 6 of the EU's Foreign Direct Invest- ment (FDI) Regulation states that “Member States shall notify the Commission and the other Member States of any foreign direct investment in their territory that is undergoing screening”, Member States appear to maintain a large degree of discretion on whether to notify the Commission. For instance, in 2022 a total of 23 notifications involving China were submitted to the EU Commission, while Germany alone recorded 37 investment screening cases involving China.

7 | Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK). “Investment Screening in Germany: Facts & Figures. All figures as per 30 January 2024” https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/ Aussenwirtschaft/investment-screening-in-germany-facts-figures.pdf? blob=publicationFile&v=2. Accessed: May 23, 2024.

8 | Pirelli (2023). Press Release. June 18, 2023. https://press.pirelli.com/press-release-18-june-2023/.

Accessed: May 23, 2024.9 | European Parliament (2018). Briefing EU Legislation in Progress. “EU framework for FDI screening.” January 2018. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/EPRS-Briefing-614667-EU-framework-FDI-

screening-FINAL.pdf. Accessed: May 23, 2024.10 | JD Supra (2023). “Ireland Introduces Foreign Investment Screening Regime.” December 1, 2023. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/ireland-introduces-foreign-investment-5346967/. Accessed: May 23, 2024.

11 | CIRCABC. https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/aac710a0-4eb3-493e-a12a-e988b442a72a/library/ f5091d46-475f-45d0-9813-7d2a7537bc1f/details?download=true. Accessed: May 23, 2024.

12 | Crowell & Moring LLP. “A New European Commission Proposal on Foreign Direct Investment Screening: Towards Greater Harmonization?” https://www.crowell.com/en/insights/client-alerts/a- new-european-commission-proposal-on-foreign-direct-investment-screening-towards-greater- harmonization#:~:text=Currently%2C%2024%20out%20of%2027,into%20force%20during%20 Q2%202024. Accessed: May 23, 2024.

13 | Journal of Chinese Academy of Science Issue 3 (2024). https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/EXCvMG67t-n tkddujGOA. Accessed: May 23, 2024.