Europe’s position in the US-China trade conflict: It’s the exports, stupid

As Washington and Beijing do battle over trade, Europe is seen to be in a strategic dilemma. Maximilian Kärnfelt says this ignores a simple political calculation that favors the US.

The US-China trade conflict has bred the truism that Europe is in a tough spot: Washington and Beijing would each like Europe to support them and European nations are struggling – and will continue to struggle – to choose between US skepticism towards China, and China’s wish for the trade order to remain as it is. But experience suggests Europe’s politicians will be more tempted to side with the US than China – and that one of their most important reasons will be Europe’s greater dependence on the US as its biggest export market.

Staying out of the neighborly quarrel between the US and China is no option for Europe as both countries are doing their best to involve it. Global trade has become increasingly politicized. The Trump administration, for example, has imposed tariffs on some European industries with a nod and wink that progress in areas such as restricting Huawei’s access to the European market may help remove them. For its part, China is supporting smaller European countries in exchange for political support within EU institutions.

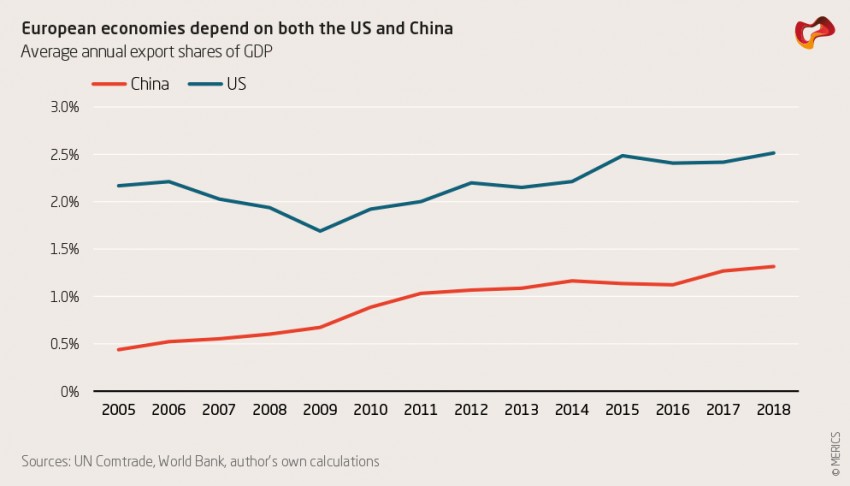

Globalization has ensured that exports to China have become an ever-bigger part of European gross domestic product (GDP) in the past ten years. But over the same period, the importance of exports to the US to European GDP rose easily as much. With some exceptions, European countries export far more to the US than they do to China. In 2018, the European Union’s 27 members and the UK exported an average of 2.5 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) to the US – Germany, the largest European economy, even 3.5 percent. The region’s exports to China were much lower, at 1.3 percent of GDP (Figure 1).

UN trade data from 2018 shows European countries export more to the US than to China. Only a few European countries at the EU’s periphery, such as Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, export a larger share of their GDP to China than to the US. It is true that all European countries import more from China than the US. It is within the realm of possibility that the cheap consumer goods that this brings Europe might generate more economic benefits than the income from exports to the US does. Figuring this out is no easy task for economists. But while we do that, politicians and the public rightly or wrongly already seem to have made up their minds, typically privileging exports over imports.

There is a strong tradition of public discourse that represents exports as being more important than imports. In trade negotiations diplomats who agree to lower import duties are said to make sacrifices, while those that convince their counterparties to lower duties are said to make gains. In that vein, US President Donald Trump has used tariffs to restrict foreign imports into the US, while battling with Beijing to allow US companies to export more to China. Similarly, the Brexiteers’ premise that the EU needs the UK more than the UK the EU was founded on Britain’s importance as an export market for continental companies.

There is a political bias to privileging exports over imports

Of course, international relations are bigger than trade alone, as any number of security issues demonstrate. But a clear political bias to privileging exports over imports is common. Chancellor Angela Merkel, for one, hopes to successfully steer Germany through the coronavirus crisis so that it can maintain its position as an Exportnation. So in disputes to come, European policymakers’ economic reasoning more probably will result in them fearing economic pressure from the US more than that from China. Rightly or wrongly, its exports to the US will be an important factor in making Europe side with the US.

Indeed, in Europe’s supposed struggle to choose between US skepticism towards China and China’s wish for the trade order to remain as it is, European leaders have once already sided with the skeptics in Washington. This is illustrated by its treatment of the Chinese telecom giant Huawei. Both the EU and the UK are introducing rules that impose some level of trade friction, making it more difficult for Huawei to construct its 5G networks in Europe. Tradition and precedent suggest that Europe’s large export flows to the US will remain a major determinant of the complex triangular relationship between the EU, the US and China.

Europe’s policymakers will get dragged deeper and deeper into the trade war

European policymakers will be careful not to risk the income earned by exporting to US. China could, of course, encourage more domestic consumption, potentially providing Europe with an export market of the same size as the US. But due to stalling reform progress Chinese demand is weak and the government has had difficulties stimulating it. Furthermore, China’s GDP and GDP per capita growth, predictors of trade flows, are slowing. This is partly because of a long-term economic slowing, but also because the coronavirus devastated growth. China will not replace the US as Europe’s most important export market any time soon. As a result, Europe’s policymakers will continue to favor the US over China and get dragged deeper and deeper into the trade war at Washington’s side.