Xi’s Control Room: The Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform

China’s leadership has institutionalized agenda-setting and supervision within policy making around Xi Jinping. A look at the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCDR) (中央全面深化改革委员会) – a supra-ministry used to accelerate priority reforms of the Xi leadership – can tell us a great deal about the potentials and pitfalls associated with this trend, explain Nis Grünberg and Vincent Brussee in this MERICS Primer. The analysis is accompanied by a slidedeck that provides context and deeper insights on the topic.

The role of leading small groups and central commissions

“Leading small groups” (LSGs), of which thousands exist across all administrative levels in China, are important ad hoc organizations tasked with coordinating work on specific policies, complex issues, or events across administrative bodies. Central commissions are their more potent siblings – institutionalized LSGs operating as political supra-ministries, which have become key decision-making bodies on major policy issues. They are the organizations shaping the “top-level design” policy “in important areas of national rejuvenation […] under personal leadership of Xi Jinping.”

As party organs with authority over both party and state administrations, central commissions greatly enhance the central leadership’s coordinating (and controlling) power. They also perform an important function within China’s governance system. They are able to break through the PRC’s otherwise highly fragmented bureaucracy, substituting a clear hierarchy and mending a chronic lack of horizontal bureaucratic coordination resulting from the top-down reporting structure also present within ministries.

Principle among the central commissions is the Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCDR). The core executive organ for Xi’s approach to steering policy making, the CCDR is responsible for supervising the drafting of priority reform policies within the central party-state administration.

The commission was initially established as an LSG during the so-called Third Plenum in 2013, which saw the adoption of a new policy program by the central party leadership outlining 60 major reform areas to be addressed. Entitled “Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms”, this quickly became one of the most widely noted policy documents of recent decades, essentially reading as the – then new – Xi administration’s political program for reforms in party organization, financial regulation, environmental protection, and many more areas.

As a party organization tasked with the direct supervision of policy making by party departments and state ministries, the CCDR is a perfect illustration of how China is fusing party and state organizations into one organically integrated administrative system, all reporting to the “core” – Xi Jinping. The CCDR was upgraded to a central commission in 2018 along with four other LSGs: Finance and Economy, National Security, Foreign Affairs, and Cybersecurity and Informatization, in order to “strengthen the role central CCP bodies have in policymaking and coordination.” All are chaired by Xi Jinping. In total, he identifiably serves as the chair of at least ten central-level LSGs and commissions. This offers him greater direct control over policy implementation.

The CCDR as policy accelerator

Organizationally, the CCDR secretariat is located within the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Central Policy Research Office (CPRO) (中共中央政策研究室). The party’s key policy think tank, the CPRO is responsible for researching and drafting major documents and speeches for the central leadership. This puts it at the very heart of policy making. The CPRO is itself located within the CCP’s General Office (中国共产党中央委员会办公厅, or 中办), the nerve center of the party, which codifies intra-party regulation and is headed by Xi ally Ding Xuexiang.

With at least two dozen ministerial-level leaders gathered under Xi’s chairmanship, its offices plugged into the party’s central administration, and its organizational mission to drive priority reform policies, the CCDR is the pinnacle of the “individualized centralization” of power under Xi. Given its mission and members’ authority, it outranks all decision-making bodies below the Politburo – including the State Council – and institutionalizes the CCP center’s grip over policy making.

The CCDR is organized into six subgroups to better facilitate the direct coordination of policy drafting with the responsible ministries and departments:

- Economic and Ecological Civilization System Reform

- Democratic and Legal System Reform

- Cultural System Reform

- Social System Reform

- Party-Building System Reform

- Discipline Inspection System Reform

Each subgroup has a specific policy focus and its own office and high-ranking director. Vice Premier Liu He, for example, serves as the director of the Economic and Ecological Civilization System Reform Group.

In addition to its impressive mandate and authority, the frequency with which the CCDR meets is also significant, as is its workload. The commission, which meets roughly every six to eight weeks, has convened 66 times since early 2014 and has deliberated on 542 high-profile policy documents. Evidence suggests that the CCDR effectively fast-tracks policies by “deliberating and passing” (审议通过) them before they are formally released by the relevant authority. The fact that policies passed by the CCDR are regarded as taking immediate effect is indicated by several ministerial notices, and suggests that the commission exercises a de facto legislative function in relation to the policies within its scope.

Broad policy mandate with a strong focus on structural and legal reforms

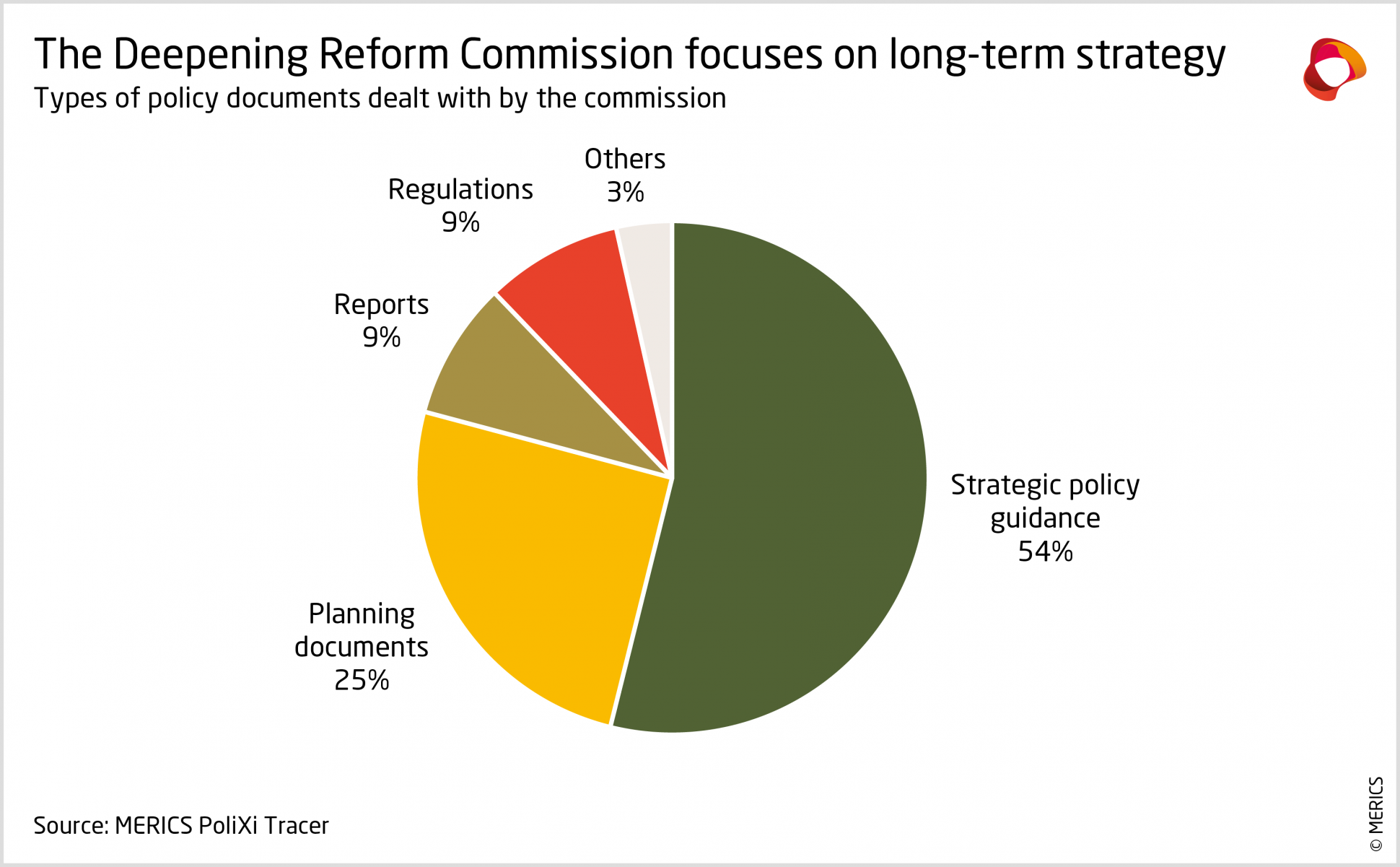

The Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform is directly involved in shaping China’s future development in the policy areas it covers. Over seventy-five percent of its policy documents concern policy guidance or long-term plans. These documents outline broad requirements, but rarely put forward concrete measures or targets; the implementing agencies are left to figure out the details. A network of CCDR mirror organizations in governments down to the county level, as well as large state-owned enterprises (SOEs), then oversees the detailed implementation of policy guidance and plans at local levels.

Over three quarters of the CCDR’s policy documents (of those publicly released) are later formally issued by the party state’s top decision-making bodies: the CCP Central Committee (CCPCC) and the State Council. This further illustrates the CCDR’s overall role as a forum for strategic policy development. It also confirms the commission’s effective place at the top of China’s bureaucratic pyramid as it has the formal right to approve policies all the way up to the CCPCC.

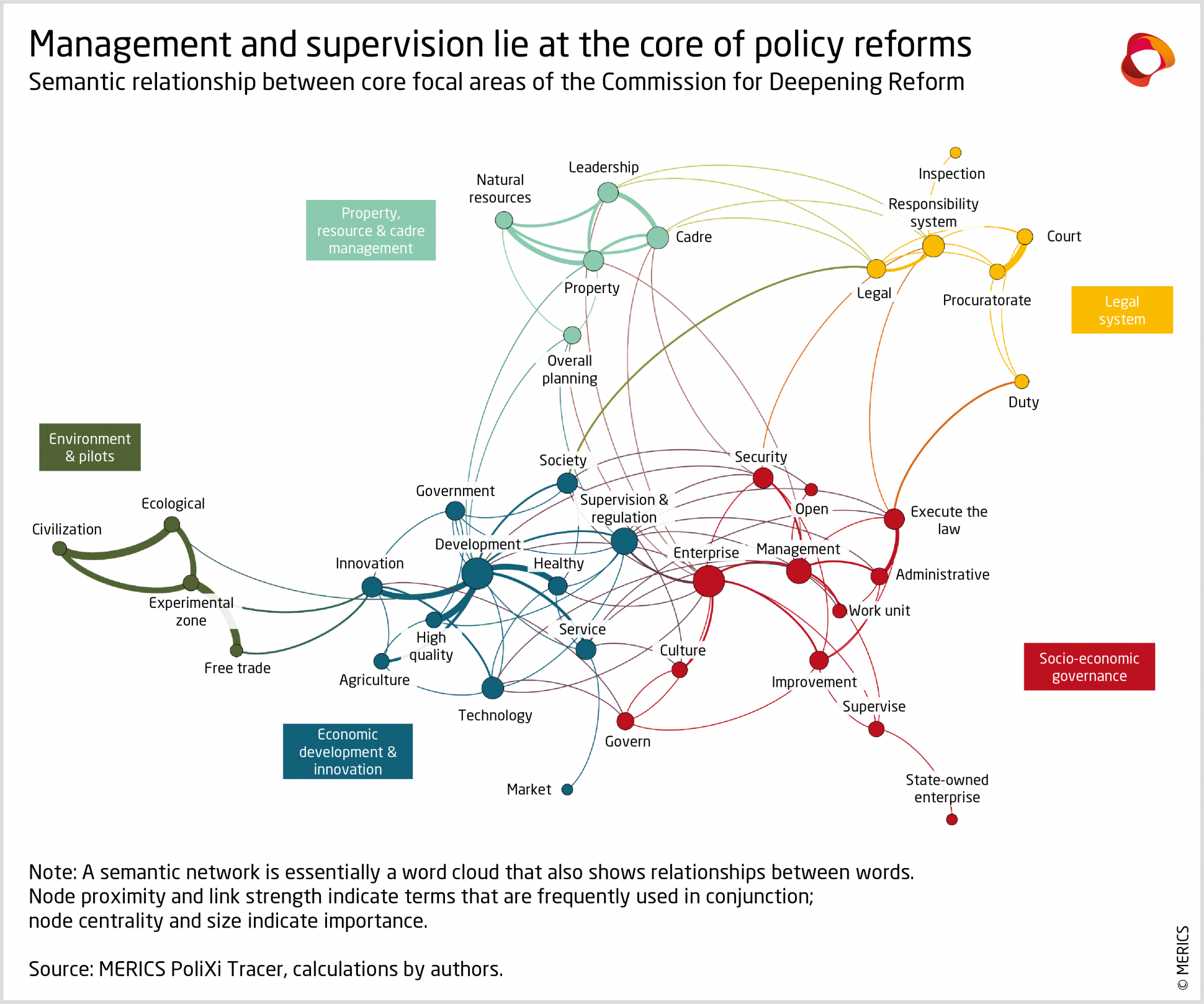

The policy areas covered by the CCDR reflect the broad scope of its founding document, the 2013 Decisions, and include party organization as well as structural socio-economic and legal reforms. The diagram below, based on the content of CCDR-deliberated policies, shows the semantic relationship between these different core focal areas. Frequently mentioned and occupying a central position in the network are issues such as supervision, management, and “healthy development” – a policy euphemism for the prioritization of government-guided long-term development over short-term corporate interests.

This confirms that these are cross-cutting issues that are central to the work of the CCDR and shape its operations. In creating these supervisory structures, the CCDR is able to deeply embed its power in China’s system without needing to focus on the nitty-gritty details.

Micromanaging policy: the CCDR’s closed-loop policy supervision

The large number of policies that have passed through the CCDR, coupled with the public record of its involvement in subsequent policy making, make it possible to identify the processes involved in CCDR-led policy drafting.

Each year, the commission identifies key reform priorities within its designated domains in its annual work plans (工作要点). It delegates these policies to a consortium of ministries and departments under its control, which bears the responsibility for researching and drafting. The drafting agencies then appear to regularly report back to the commission or the appropriate subgroup for validation or further guidance.

Once this process is complete, the finished draft policy document is submitted to the CCDR for formal approval. During a meeting chaired by Xi and attended by other central leaders and the heads of relevant agencies, the commission deliberates and passes the policy, at which point it is considered to come into effect. Xi Jinping also delivers a speech that conveys the “spirit” of the policy and provides guidance for its implementation. Thus, the role of the CCDR here is not just to formally pass the document but also to convey the context and normative intention behind the policy.

Following official approval, the implementing agencies organize study sessions to further develop their understanding of the “spirit” of the policy as conveyed during the meeting and in Xi’s speech. The commission also regularly reviews reports on the implementation of its policies, for instance on anti-poverty work or local experiments. These reports are commonly submitted by local Comprehensively Deepening Reform Commissions, which are involved with specific regional policies and projects. After the presentation of these reports, the commission issues instructions that often lead to the implementation of new policies.

The CCDR thus functions rather like a control room. It theoretically allows Xi and other leaders to manage and supervise the entire policy cycle without being involved in every single deliberation. However, the actual degree of control they wield is uncertain. The CCDR relies heavily on effective feedback loops with lower-level agencies. If the information it receives is inaccurate, this will affect the quality of its decisions. Study sessions may also end up as formalistic signaling exercises rather than providing meaningful policy guidance. Nevertheless, in theory this process has hard-wired feedback loops into policy drafting on a broad array of issues seen as priorities by the party center.

Centralization can mean policy acceleration and better coordination – but at the cost of transparency, accountability, and flexibility

The CCDR, along with the other central commissions, is part and parcel of the centralized, even personalized policy making seen under Xi Jinping known as “top-level design”. Greater levels of direct top-down supervision are meant to translate into the faster and more effective implementation of important structural reforms by overriding China’s notoriously fragmented and poorly coordinated bureaucratic decision-making processes.

This perspective is supported by the data, but only to a certain extent. According to the lists issued by the central and local CCDRs, work on priority policies indeed seems to have accelerated. On the flipside, those policy areas without CCDR or other top-level agency involvement may be dogged by sluggish progress. The extent of the resources required by CCDR-related work (from policy drafting to reporting) in the ministries and departments involved is also unclear but, given the number of policies issued by the CCDR, must be non-trivial. This level of centralization also means that Xi and other Politburo members (and their aides) have to set aside significant resources to follow and supervise policy making on a vast number of issues. A shortfall in resources could therefore potentially clog the process.

A further disadvantage of the centralized policy-making approach is the lack of transparency. Thanks to the public documentation of the process in case of the CCDR (albeit still very limited but open compared to other commissions), it is possible to gain a picture of its involvement in policy making. In general, however, the work of the central commissions is highly untransparent. Rather less information can be found on the Cybersecurity and Informatization Commission, and even less on the National Security Commission (NSC) which also has a web of offices throughout China. While in theory all central commissions hold similar rank, the NSC should be seen as the most authoritative, given both the nature of its remit and the degree of securitization under Xi Jinping. However, it appears that the CCDR is most actively involved in regular policy making due to its broad “reform” mandate. It also appears to meet twice as often as other central commissions; only the Politburo and its Standing Committee meet more frequently.

The CCDR represents the institutionalization of a CCP organ at the top of a genuine policy-making system. It has broader responsibilities than any other ministry and higher authority than the State Council (which ironically still needs to formally pass the policies developed by the CCDR to legally codify them). It therefore provides an excellent illustration of the governance model pushed by Xi Jinping: an administration in which state bureaucracy is centered around the political core of the party and with Xi himself at the heart of decision making, holding veto power over all major issues.

While this approach may bring certain advantages, the CCDR example makes it clear that there will also be a price to pay when it comes to policy innovation, local flexibility, and the availability for decentral correctives to faulty central directives. With the 20th party Congress imminent, and Xi firmly in power, certainly the centralization of policy guidance, supervision, and dominance of central priorities will continue to weigh heavy on cadres at all levels throughout a still very heterogenous China.