Serving the people by controlling them: How the party is reinserting itself into daily life

Key takeaways

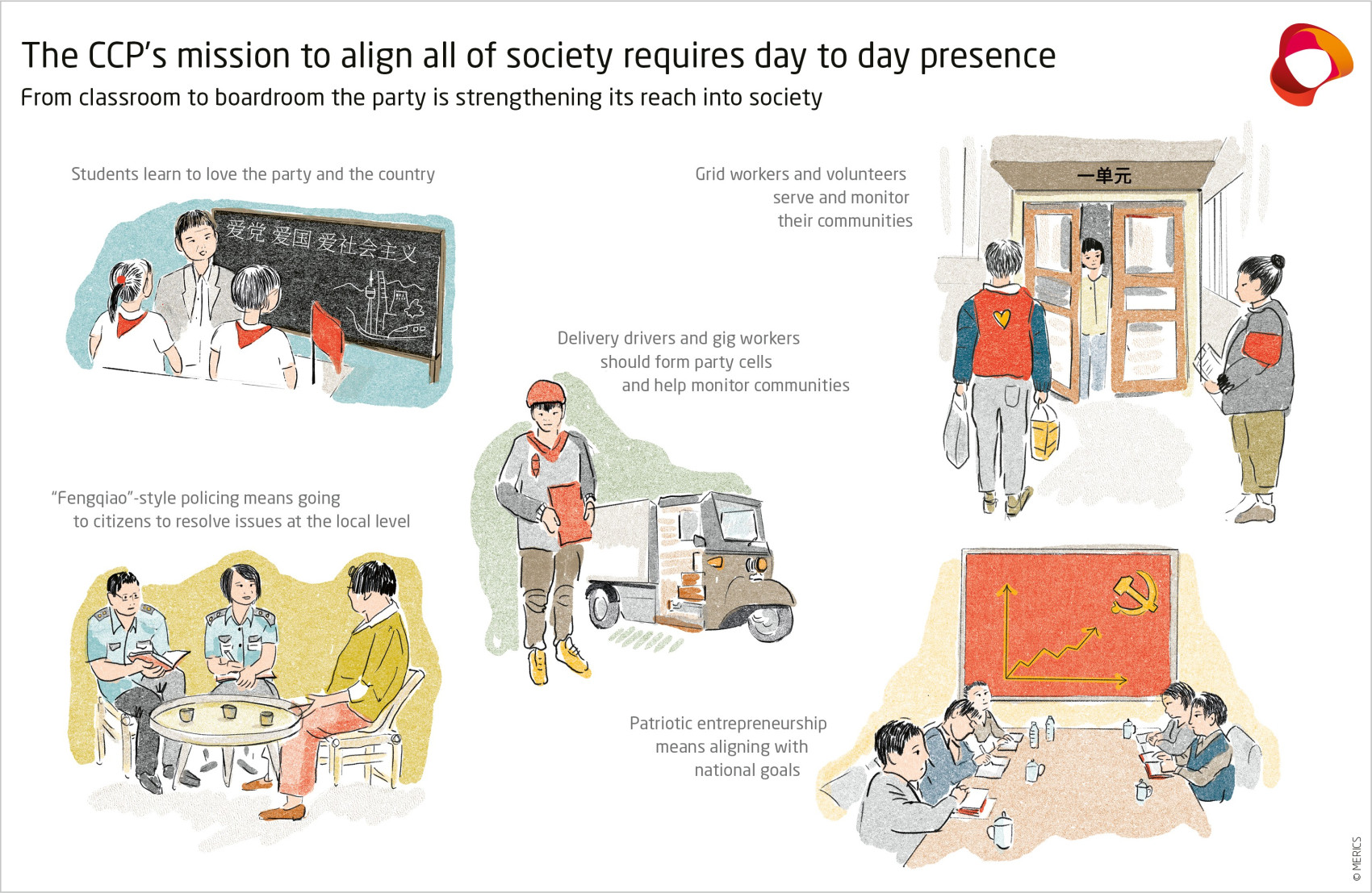

- China is building a new model of social governance that merges Mao-era grassroots mobilization with digital surveillance and party-led service delivery. This model is not just about repression, but about reshaping society to internalize Chinese Communist Party (CCP) norms.

- China’s leadership oversees a party-state apparatus that is bigger, better organized and resourced than ever before. Xi Jinping is focused on further expanding the CCP’s presence in private companies, urban communities and villages.

- A complex of institutions is tasked with promoting party hegemony in society. New rules and agencies, such as the Central Society Work Department established in 2023, seek to reinsert the party into new sectors of the economy, workforce and volunteer organizations that had developed beyond its reach.

- The party state’s modernization of social governance fuses improving social services with tighter political control. Providing better, locally adapted public services is part of officials’ community work, but the system of provision also works to ensure citizens abide by party-set political rules as well as state laws.

- Political-ideological education is promoted to prevent a diversity of political views and efforts to self-organize. Party building efforts, patriotic campaigns and political control come together at grassroots levels to mobilize officials, citizens, entrepreneurs and the youth to support a party-defined vision for Chinese society.

- Enormous resources are being poured into molding society and expanding grassroots surveillance. The new social governance approach relies on various frameworks like the “grid management” system and the “Fengqiao experience” to generate a high party presence at neighborhood level. These frameworks are meant to maintain social peace by running grassroots campaigns, mobilizing volunteers, fostering self-correction and resolving issues at local level.

- The new social governance approach aims to ensure Chinese society’s readiness to struggle. In a time of slowing economic growth and geopolitical friction, citizens and entrepreneurs are asked to contribute to – and, if necessary, sacrifice for – the greater good of modernization and national rejuvenation.

- The CCP’s expanded grassroots presence is a source of authoritarian resilience. The party state’s combined delivery of care, ideological conviction and coercion has been effective at keeping social fragmentation and dissent at bay.

- Maintaining party presence and steerage is a challenging and costly endeavor. Bringing society at large in line requires significant human resources and does not equal full buy-in and commitment. Despite decreasing government finances, the party still needs to deliver tangible benefits, especially for younger generations.

- This has implications for international stakeholders: ever-stronger party steerage in corporate management, increased ideological alignment and repression of dissent, growing external defensiveness, as well as renewed efforts in social policy to maintain public support.

New challenges propel a return to the grassroots

Today, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is larger, better organized and resourced than ever before. CCP general secretary and president Xi Jinping’s first term in power was dedicated to centralizing power and bringing the state under party guidance. The second term focused on establishing macro-steerage over the private economy, especially big tech companies and strategic sectors. Now in his third term, China’s leader is seeking to expand the party’s grassroots presence at the lowest levels of social organization, in urban communities, private companies and villages.

The CCP leadership regards governing the people and keeping society “harmonious”, stable and united as a core task. Under party leaders Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, the party’s influence in society was weakened. This was not a conscious policy choice, but a byproduct of swift economic and social transformation set in motion by the reform and opening policy. Rapid change lessened the party’s presence in daily life, which during Mao’s era wielded control over everything from job assignments to housing and marriage decisions. The state-owned sector had an immense role in organizing communities. Its slimming down further opened up room for a private sphere in society.

Under Xi’s guidance, the party is now systematically reinstated into all layers and spheres of society. In the eyes of the leadership, increased mobility and pluralization have led to social dispersion (离散化), fragmentation (碎片化) and hidden ruptures (隐性断裂) in society. The past decade has seen a new ambition to penetrate daily life, both online and offline to counter this trend.1 During the 2025 National People’s Congress, Xi stressed the need to strengthen “society work” (社会工作一定要加强) as a key responsibility of local officials.2

Social governance (社会治理) is seen through the lens of socio-political stability, regime security and national interests. The new White Paper on “National Security in the new Era” released in May 2025 acknowledges that China’s society is undergoing profound changes, requiring stronger efforts in social governance to build a modern, vibrant and well-ordered society.3 In state media, frequent praise is voiced for patriotic entrepreneurs who support national technology ambitions. China’s education sector is reshaped around notions of patriotism. A new law on ethnic unity is underway, aimed at building “a strong sense of national identity, reinforcing the Chinese people as one cohesive community.”4 These are all indicators of how important a loyal and politically aligned citizenry is to the party.

A multitude of proactive, largely human-driven social governance initiatives currently underway are designed to revive the impact of party-state rules on daily conduct for businesses and individuals. At grassroots levels, party-building, patriotism, and control come together to mobilize officials, citizens, entrepreneurs and the youth to support party-defined visions for Chinese society. Such localized initiatives play a key role in building resilient party state systems and a supportive citizenry to prevent security and stability challenges from emerging.

The vigorous drive to establish party leadership across all spheres down to the individual level is also a response to socio-economic stress and latent political disillusionment. Such frictions are widespread, especially in parts of the private sector and urban population, who were hit hard by the enforcement of China’s intrusive zero-Covid policies.

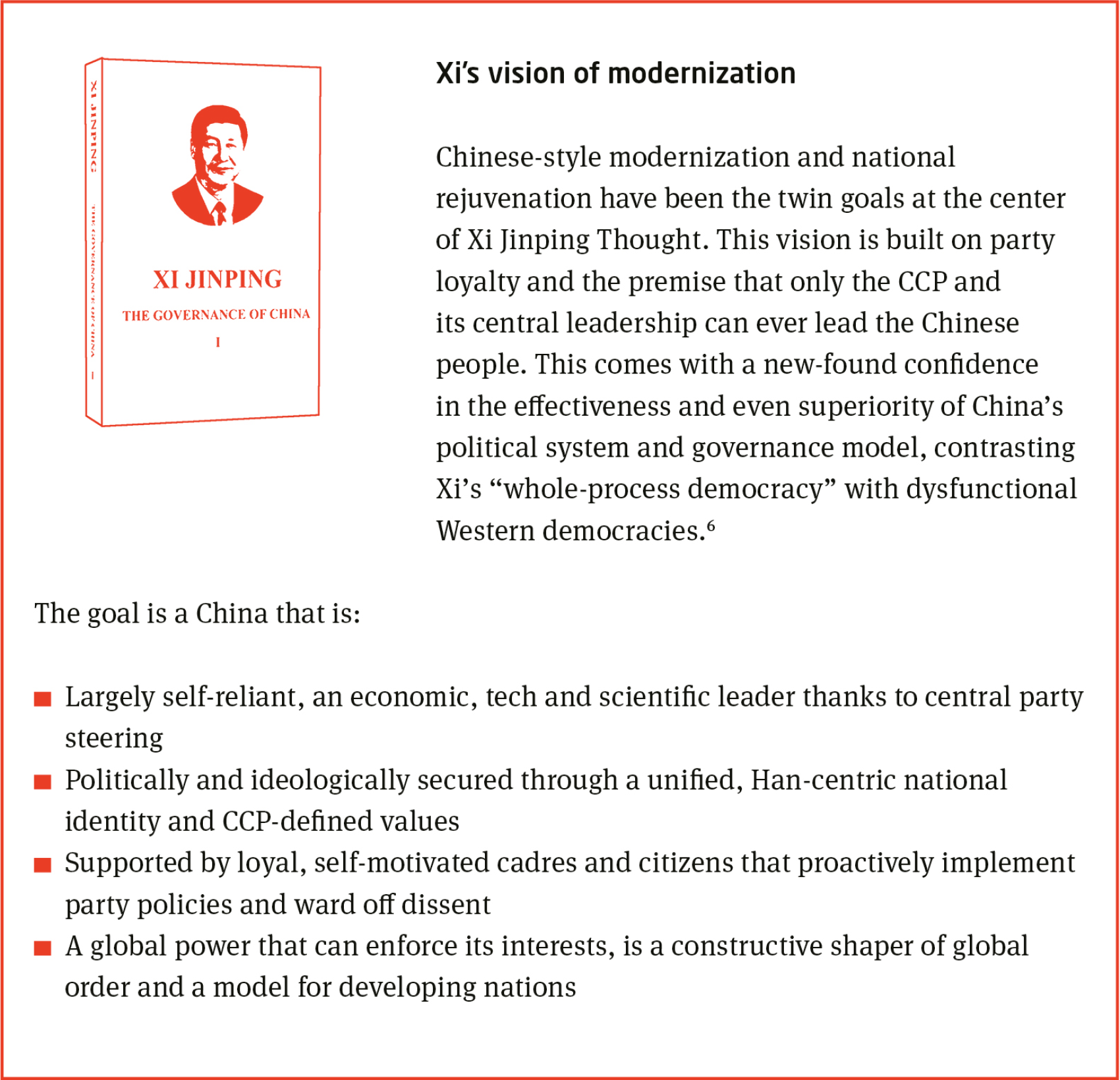

Most importantly, the CCP’s quest to reassert ideological primacy is serving the big vision of achieving Chinese-style modernization and national rejuvenation. In times of geopolitical headwinds, slowing growth and a structural transformation of the economic model and labor market, maintaining loyalty to the party and a general readiness to struggle for national goals is seen as vital for China’s path.

The guiding principle: "The party leads on everything"

Early on, Xi focused on establishing personal power through anti-corruption campaigns and deep structural reforms to reintegrate the party and state systems.5 Legal codification of party leadership – from the Constitution to lower-level regulations – has been systematic, and most statutes now explicitly reference it.

Subsequently, from the late 2010’s, a new phase of party and social governance began, focused on ensuring discipline and alignment throughout the CCP itself. “Xi Jinping Thought” provides a vision of how the party should deepen its social reach so its views on social and economic organization are followed through at local levels. Maximum internal alignment is regarded as necessary for the mission to turn China into a powerful, self-reliant, geopolitical player and realize Xi’s vision for China’s modernization.

Xi's mission to strengthen ideology and discipline the party

The push for alignment and loyalty is now being driven into the lowest capillaries of the party-state system, the frontline officials at local levels. Xi stressed grassroots work at the CCP’s 103rd anniversary events, saying establishing cells in “all new types of economic and social organizations” was key to “letting the banner of the party fly high across all parts of society.”7

With 5.2 million grassroots organizations and around 100 million party members, a lot of organizational power could be mobilized.8 The CCP has added almost 10 million new members over the past decade. Today, one in 11 adult Chinese citizens is a CCP member, and the party views itself not as a political party as understood in liberal democracies, but as a social movement and a foundation of social order.

Members must follow guidance on how to be a good party member in the new era (做新时代合格党员). They also face waves of disciplinary campaigns against corruption and political offenses, ranging from failure to implement policies to reading the wrong books. The implicit distrust is revealed in increasing travel restrictions for cadres and officials.9 After internal rectification and self-revolution, disciplined cadres should take the political gospel into society as part of “party building” work (党建).

Xi’s social governance project remolds society in the party’s image

Xi’s aim is to restore the party’s hegemony over wider Chinese society,10 in line with a Mao-era slogan re-embraced into the party constitution in 2016: “Party, government, military, society, education; East, West, South and North, the party leads on everything”. The party should occupy the “controlling heights” of economy and politics and be organically integrated into society.

True hegemony requires popular acceptance and support. To achieve “national rejuvenation” by 2049, the centennial of the CCP’s rule over China, suppression should be a back-stop not the norm. Educating and persuading the public of the CCP’s mission and ideology is therefore a central task.

Social governance is increasingly viewed through the lens of security.11 Although the party stresses law-based governance, protection of citizen’s rights and interests, provision of public service and a guiding moral compass, a closer look at writings, institutional changes and policy initiatives show grassroots governance and administration are becoming more tightly integrated with propaganda work, digital surveillance and the security forces.

Digital surveillance built up over 30 years has created one of the world’s most powerful policing apparatuses, a preventative structure that is seamlessly integrated in citizens’ daily lives.12 Yet the human side of the new social governance system is equally important, as party members can play a proactive role in transmitting norms, values and expectations as well as collecting information.

The institutional machinery of grassroots hegemony

Establishing hegemonic social control means making the party line a policy standard; leading narratives in media and public discourse; reshaping education; and having a presence in private enterprises, civil organizations, neighborhoods and religious and ethnic communities. And having the monitoring capacity to step in when push back or risks arise.

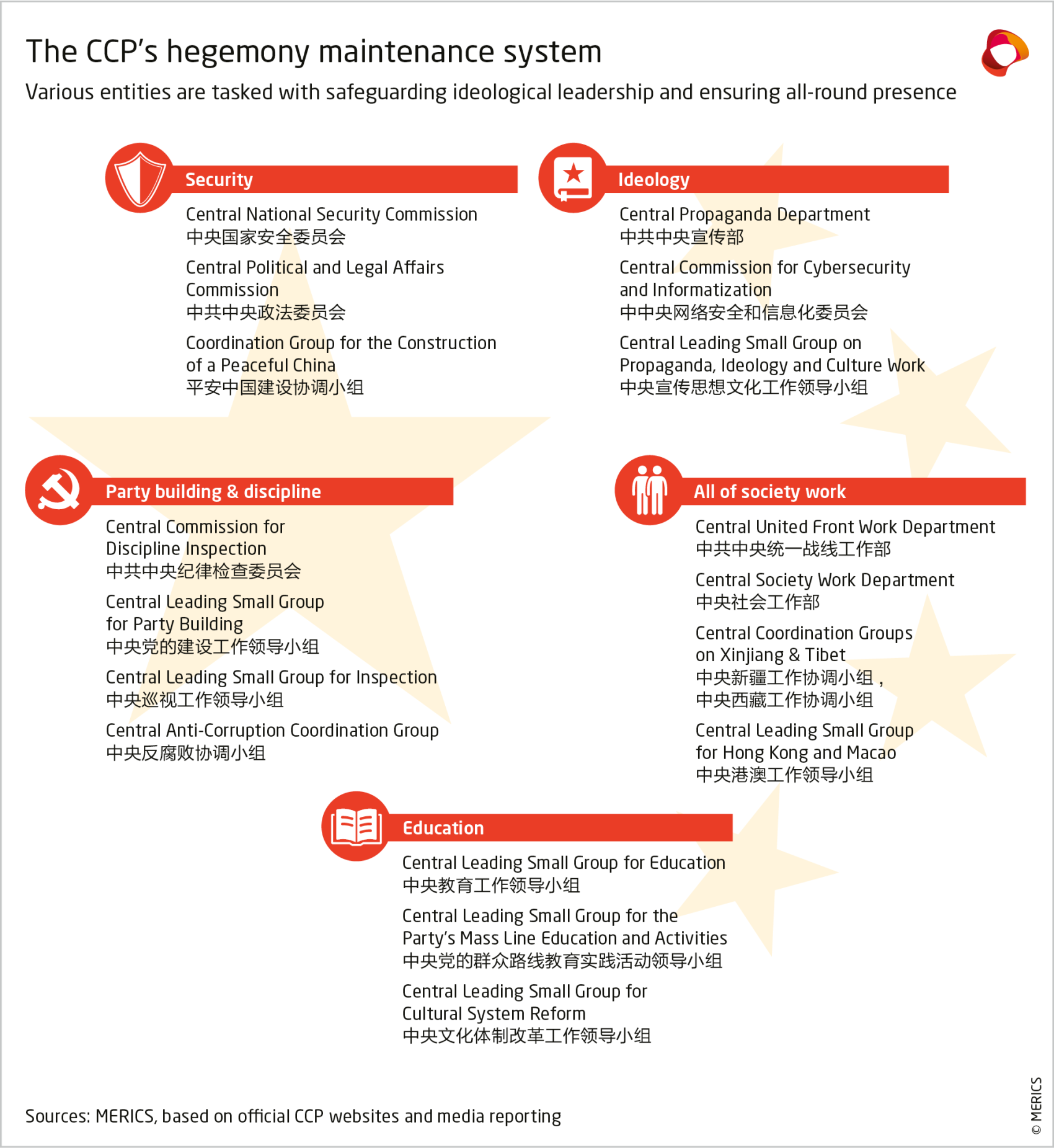

A vast bureaucracy is tasked with the many aspects of this all-of-society project. Institutional changes reveal policy concerns and perceived areas of friction, as evidenced by a greater focus on private enterprises, education, and citizens at large. Taken together, these projects aim to bring all aspects of social organization into alignment with the leadership’s vision of Chinese society.

A complex of institutions is tasked with party-building and ideology work

The bureaucracy built around social control and party-building work has become its own institutional network. At the central party level, key commissions, leading small groups (LSGs) and central work departments are tasked with achieving grassroots hegemony (see exhibit 1). Together, they cover a broad range of issues: maintaining security and ideological primacy; party building and discipline; party steerage in the private sector; education and culture; policies relating to ethnic and religious groups as well as molding society at large. These central party organs are mirrored at all administrative levels and guide the work of state administrations, from the State Council down to village level.

The institutional framework for carrying out political education and all-of-society efforts has been expanded, including through the establishment of the Society Work Department, which now sits alongside the United Front Work Department (UFWD) as a ministry-like department under the central party leadership. The UFWD is mostly known abroad for its foreign influence work. Its main domestic tasks are to safeguard national sovereignty, security and national interests by building popular support for the party.13 Its primary targets are non-CCP social groups, key individuals, and non-state organizations, such as the eight democratic parties, ethnic minorities, religious groups, intellectuals and private businesses. The UFWD has front-line workers pushing party ideology and political education in social spheres where the party lacks control. The goal is to build alliances (i.e. a united front behind the party) and fight “hostile forces at home and abroad.”14

The Society Work Department was created to extend the CCP’s reach

The Society Work Department (SWD) was established in March 202315 – shortly after the end of zero-Covid policies in January that year and the ‘A4 protests’ in late 2022. It is a new central party organ tasked with party building in small enterprises and industry associations, guiding volunteer work and overseeing petitions from aggrieved citizens.16 Its powers and competencies make clear it exists to facilitate control over communities and non-public organizations such as private enterprises and associations where existing styles of united front-work fall short. It represents a new approach to the private sector, where political trust has been shaken by bankruptcies, debt, employment and wage issues.

The SWD is tasked with supervising the general direction of social governance at grassroots levels and also channels information upwards on local conditions and tensions. By February 2024, all provinces had set up SWDs, which was a task given to provincial, municipal, and county-level party committees.17 The SWD can be expected to take a stronger role in community-level party building, even if responsibilities overlap with other structures.

The SWD has three main functions:

- It will be linked with party committees and party cells to promote party building in private and mixed-ownership enterprises, industry associations and chambers of commerce.18 It must strengthen party-building work among new employment groups and “small, individual, and specialized” enterprises, which covers about 97 percent of all businesses, as there are 170 million registered small and micro enterprises and individual industrial and commercial households.19

- Ensuring the party steers the civic realm of non-profit social organizations and volunteers. The SWD seems designed to curtail networks outside of CCP and promote and harness citizens’ willingness to contribute to the public good.20 Qiushi, the party’s main theory outlet, estimates there are 235 million registered volunteers at grassroots levels, who are key potential assets for civil society under party state guidance.21

- Notably, the SWD now oversees the National Petitioning Bureau (国家信访局), which was subordinated to the new party structure in 2023. This positions it as a new institutional base for responsive governance and a vantage point to identify social dissent.22 This seems to be a direct response to the rise of conflicts, petitions and protests by disgruntled workers and homeowners over wage losses, working conditions, payment defaults and lost savings.

How the CCP strives to exert omnipresent guidance

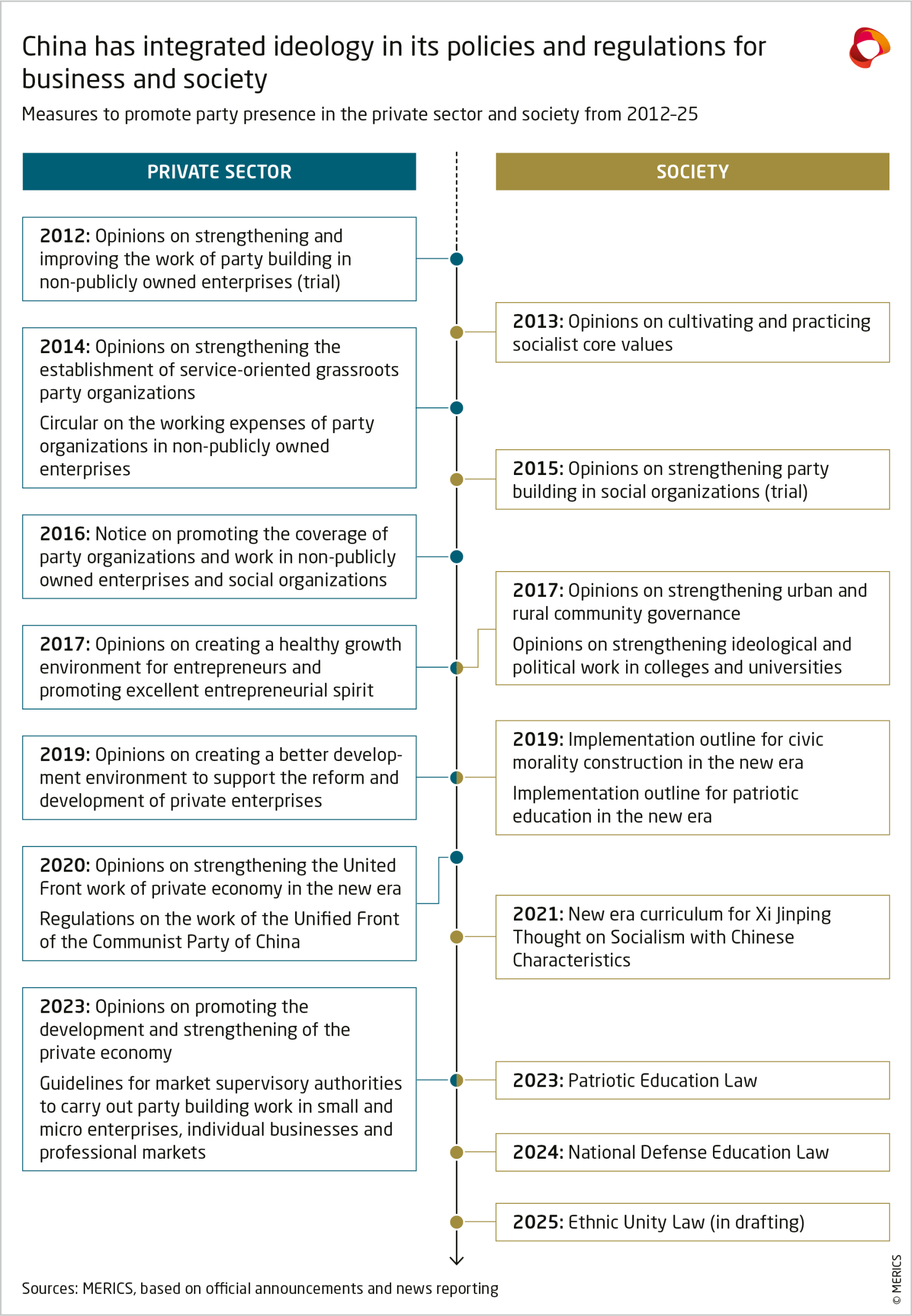

From 2012, the new leadership around Xi Jinping put significant efforts into repressing what it deemed undesirable, reining in independent civil society, curbing advocacy in social or gender-related matters, restricting information flows, tightening control over ethic and religious groups and cutting ties with international actors – especially Western NGO – for fear of subversion.

The focus is now shifting to fostering a mainstream national identity and day-to-day alignment of the private sector, workforce and citizens at large. Increasingly, the party state wants more than passive compliance, preferring proactive, vocal alignment and support. Since 2023, there has been a distinct turn to nationalism, patriotism and defense readiness as a source of social cohesion, with anti-Western undertones and a majority Han-centered ethnic identity.

Patriotic entrepreneurship: aligning private firms with party goals

The party sees private firms as one of the “battle grounds” where party influence is lacking. The private economy is low on resources and confidence, especially after the stringent zero-Covid measures. A cautious discussion has reignited among economists and officials about the party state’s control over the private sector, though it is marginal to central-level plans to penetrate the sector.23

The need for entrepreneurs to align with politics and follow the CCP’s leadership is stated in policies issued by central party organs and the state administration. In 2017, “patriotic entrepreneurs” were described as those who live up to their function as “accumulators of societal wealth” and strive to become an asset for national power.24 In 2019, they were urged to contribute to the declared state goal of returning China to global superpower status.25 The real meaning of these pronouncements was felt by Alibaba and others a year later, as their businesses came under forceful political scrutiny.26

In smaller private firms, party cells are either completely absent or vary greatly in their activity levels, ranging from existing as defunct formalities to full integration with management. The party center has been pushing for “dual coverage,” meaning party cells in every private firm are fully functioning. The 1993 Company Law required every organization with three or more party members to form a party group so the goal is not new. However, the level of enforcement and scale is, with the SWD apparently serving as the driving force to implement this change.

Recently, multiple new, detailed regulations have been issued to support the efforts, though party cell influence and expansion in private firms has been observable since 2012. Party cells’ responsibilities and functions were clarified by a 2019 regulation.27 A guideline from 2021 makes party cells mandatory in firms with 50 or more employees, regardless of how many staff are party members. Cells are encouraged to recruit managerial personnel into the firms’ party group and to establish formal links with local government and party authorities. The task list in the regulation includes:

- propagate the party’s guiding policies

- create cohesion and solidarity among employees

- protect all actors’ rights and interests (within the company) establish an advanced corporate culture

- promote healthy corporate development

- strengthen personal development of employees

More policies followed, proposing party building even by single person firms and among gig workers. The latter reflects the CCP’s efforts to map and adapt to the changing social and employment landscape. New forms of work in the platform economy have given rise to new labor rights issues. Recent years have seen a series of small-scale protests by delivery drivers about harsh work conditions.28 By establishing party presence here, the CCP effectively preempts self-organization and instead takes the lead in resolving concerns on its own terms. The grassroots reach of delivery workers has now been identified as an asset: the state market regulator overseeing the gig economy issued a regulation on recruiting delivery workers for party building work and social surveillance.29

Learning to struggle: patriotic education and defense readiness

The party has released a series of policy plans, guidance documents and laws to foster patriotism, national security awareness and defense education. The current wave began in 2019 with implementation outlines for promoting citizen morality and patriotic education, then school curricula reform plans in 2020 and 2021, the 2023 Patriotic Education Law and the 2024 National Defense Education Law. These measures were modeled on similar citizen morality plans and patriotic education measures in the 1990s to early 2000s.

However, recent measures show a new level of ambition and a thirst for large-scale implementation. One notable trend is how education, from kindergarten to university, is being suffused with patriotic, national security and defense education through curricula reforms and new textbooks that stress Xi Jinping Thought and his concept of “comprehensive national security.”30 The goal is to instill the emerging generation with cultural confidence and loyalty to the party. Patriotic themes and ideological framings pop up across disciplines, even in biology textbooks talking about Chinese people’s “red genes.”31

Academia is undergoing changes too. Social scientists are tasked with helping build an “academic discourse system with Chinese characteristics” that sustains the party’s governance approach. More than 20 Xi Jinping Thought research centers and national security research centers have been established.32

As science and technology are central to Beijing’s strategy for innovation and self-reliance, scientists and research institutions are in the patriotic spotlight. Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang said in a speech at the National Science and Technology week in May 2024 that the “spiritual essence of scientists is patriotism.”33 The message: science and research are instruments for national development so scientists should actively support national objectives. The shift is also felt in international exchanges and collaboration.

The renewed drive for patriotism and defense readiness extends to the general public, with a flurry of grassroots outreach and education campaigns. Residential communities and street committees are encouraged to organize exhibitions and lectures on national security and defense. More companies are giving new staff defense preparedness training.34 The Ministry of State Security runs social media campaigns urging Chinese citizens to combat espionage and catch spies.35 These campaigns often have a strong nationalist and anti-Western undertone, making strategic use of an external threat narrative to build internal cohesion.

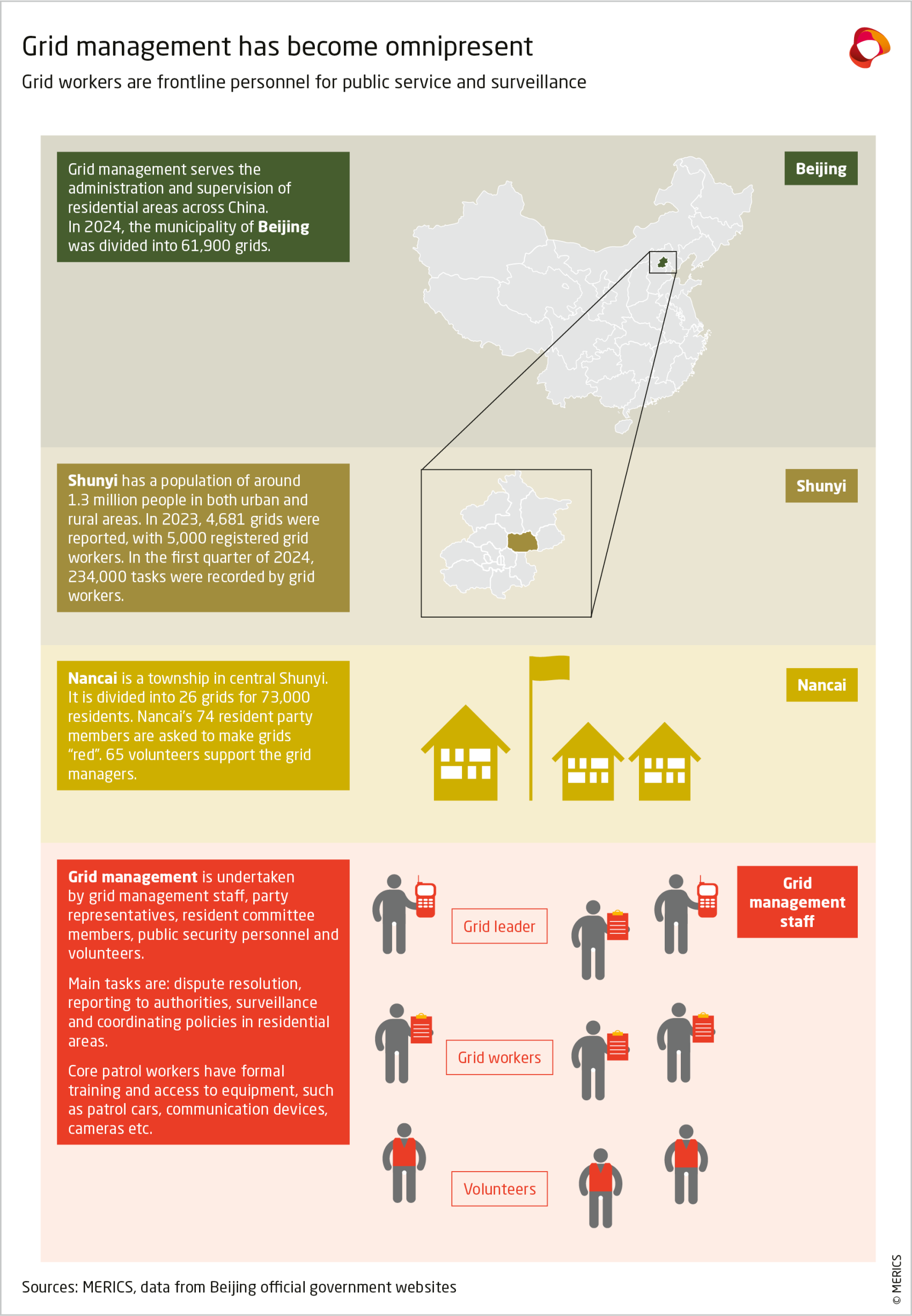

"Grid management" ensures a strong local presence

Xi’s leadership does not separate systems of public service and social control. They go hand in hand with the nation-wide grid-management system (set up from the mid-2000’s).36 New grassroots initiatives for self-management and correction have gained traction more recently, often under the governance slogan of the “Fengqiao experience.”

As part of grid management, residential areas are divided into units – or grids – usually containing not more than a few hundred households. Grid workers assigned to each such unit are responsible for a variety of tasks. It helps provide better public services, but grid workers also surveil and report on residents’ suspicious behavior and give security forces a direct line of sight into communities. This level of control comes with huge costs and logistical demands and requires constant all-of-system mobilization. Although a powerful tool of the party, the grid system is starting to show strains amid slowing economic growth and generational change.

The financial burden of grid management

The grid management system has become a crucial part of China’s governance, combining grassroots administration, public service, surveillance and policing. It represents the clearest example yet of how China’s leaders want state-society relations to be organized. Piloted in localities in 2004, today it covers nearly all residential areas, officially at least, and involves a significant workforce. During the Covid-19 pandemic, authorities revealed that more than 4.5 million grid workers were engaged in implementing the strict quarantine rules.37 Xi endorsed grids as a basic supervision and management system, they expanded in the pandemic and are now a key governance mechanism drawing in vast resources.

The vision is for citizens to be managed according to standardized norms and regulations, rather than self-organizing and solving issues heterogeneously. Grid workers, and especially CCP members, are seen as mobilized actors of the party state, with hybrid roles and authority covering service provision and social stability. The system merges public service, conflict mediation among neighbors, surveillance and stability maintenance, policing, legal work and more.38 Successful public service provision is equated with the absence of public security threats.

The dual role of grid workers, as part of communities yet agents of the party state, makes the grid management system a powerful tool for steering citizens’ public conduct. One key objective is to solve issues directly at the administrative level, as locally as possible. This includes welfare, administrative services, dispute mediation, but also monitoring residents and reporting on suspicious activities and political dissent. Grid workers’ tasks39 include:

- patrolling residential areas and documenting security hazards and damage

- conducting license and safety checks on businesses, combating illegal parking

- keeping records on residents, supporting the police in joint checks on residents and businesses

- checking on residents of interest (older or disabled citizens, informants, individuals who have raised complaints, residents flagged as problematic, etc.)

- mediating complaints and neighbors’ disputes

- organizing public education on regulations, important events and new ideological campaigns

The degree of involvement and resources grid workers have to serve (and control) their residents depends on local finances. In theory, every grid worker should get training courses and be supported by volunteers. Most localities pay grid workers between CNY 2,000 and 4,000 a month (ca. EUR 250 to 500), though affluent places like Shenzhen pay above the national average, at least CNY 5,400 and 5,600 (EUR 700-725), with an optional performance bonus of CNY 1,500 and paid overtime. By contrast, Beijing’s Shunyi district offers average monthly pay of CNY 3,200.40

Adding the cost of equipment, facilities, and training, the system is a giant investment in social stability and public service. The Shunyi district alone had around 4,500 grid workers registered in 2024, earning CNY 3,200 per month, so total salary costs were approximately CNY 172.8 million (ca. EUR 21 million). That equals public expenses of around CNY 133 per capita for Shunyi’s 1.3 million residents.

Extrapolating to the national level, at Shunyi levels, costs would be as high as CNY 186 billion (ca. EUR 14,4 billion) a year.41 Salaries and equipment varies across China, but the numbers show the significant financial burden the system imposes on already strained local public coffers.

Public finances are one of the biggest challenges as it is. China is in the process of a massive restructuring of public debt. Public coffers in many places are strained, due to slowing growth. At the same time, the to-do lists for local governments outlined at this year’s NPC keeps getting longer: Boosting the private economy, consumption and technology development, ensuring employment and welfare, maintaining social stability, necessitating strategic choices and trade-offs between different policy goals.42

Promoting self-correction: the Fengqiao experience and citizen mobilization

Political mobilization of officials and citizens, informed by party ideology and education work, has become a central part of China’s community-based governance. Under the concept of the “Fengqiao experience”, officials and locals apply a form of self-governance to solve issues and conflicts at their level, though the process is strongly guided by directives and ideology from the central party-state. Described by the CCP’s theory journal ‘Qiushi’ as the “gold standard for Chinese governance,” this concept has been revived as a way to solve conflicts directly where they arise.43 It complements the grid management concept by bringing together grassroots community administration and outreach with local police and legal-judicial units.

Fengqiao-experience activities typically include working with volunteers and instructing local citizens in ideological and legal matters, especially locally relevant new laws and regulations. Court officials travel around counties to mediate legal (or quasi-legal) disputes, e.g., on land use, licenses, or contract issues. For police stations, Fengqiao-style work gives additional flexibility towards dispute resolution and grassroots frictions, while opening up community-level governance to surveillance.

The main stated benefit is community-based political-legal education and mediation, but the Fengqiao experience doubles as a powerful political security mechanism. Its mass-mobilization aspects monitor correct political awareness down to the personal level. Its revival shows how much the central level is focused on reestablishing habitual compliance and affirmation of the party by each individual and instilling a reflex for self-correction. Grid workers and community-based informants are often the same people, and they routinely overlap with local security forces.

In 2019, the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) began upgrading police stations to “Fengqiao-style public security police stations” (枫桥式公安派出所). Over 1300 now exist to combine police work with “new-era Fengqiao-style work.” Their main task is to ensure local “loyalty to party leadership, legal service to the people, impartial law enforcement and rigorous discipline” in order to “create a secure and stable political and social environment.”45

Since 2022, Fengqiao police stations have been supported by “People’s Fengqiao-style courts,” to be established in villages and counties. This structure replaces the role of traditionally influential local hierarchies, such as families or clans, with more standardized, party-led governance – an acknowledged goal, since grassroots-courts exist to “fight against evil and illegal behavior and sustain the fight against village hegemony.”46

Successes of the model may be undermined by new fault lines

The CCP’s expanded social presence has become a source of authoritarian resilience. The combination of care, conviction and coercion has worked well to keep organized opposition at bay. The atomization of dissent and streamlining of public discourse has helped to contain social fragmentation, even as the party struggles to make good on its promises of “common prosperity” and better lifestyles. The social and political polarization the CCP observes in many liberal democracies likely lead the leadership to feel vindicated in its chosen path.

But Xi’s social governance approach puts a heavy burden on frontline workers and volunteers. The balance between social care and social control rests on how zealously, strictly and astutely they operate. There are signs of disgruntlement within the system. Grid workers complain about the workload, poor salaries, the tedium of patrols and visits, or filing reports on menial issues such as parking violations or noise complaints. Some have fallen victim to acts of violence by enraged citizens. Their enforcer-role among neighbors during the zero-Covid policy has also taken its toll.47

In light of these constraints, it may prove harder than the leadership expects to motivate key elements of the general public. Xi’s language of struggle and “eating bitterness” for the sake of national greatness reflects the conditions in which his generation was raised. Chinese citizens today grow up in relative material comfort, especially the urban youth, and have different expectations of what their country can do for them. The CCP acknowledges, “the environment is changing and the people’s yearning for a better life will be stronger; national governance must continuously adapt to these new trends.”48 Amid economic setbacks, the 2025 National Security White Paper explicitly mentioned the need to ensure the people’s sense of “achievement and happiness”, alongside increased policing.49

There are plentiful signs of a disconnect between elements of the younger generations and the elderly CCP leadership in online slang and memes that reflect disillusionment and opting out, through “lying flat” and “involution.” At the same time, publicly visible discourse is increasingly dominated by party propaganda and high-pitched nationalism. The “us-versus-them” narrative that frames China as under siege has some impact as a unifying force, especially amid current geopolitical frictions.

Conclusion: Society and business become ever more politicized

An era of decreasing intervention into economy and society has ended. The party is reasserting its dominance amid declining economic opportunities and rising international tensions. Xi sees the party as the all-round solution to China’s problems, blending “sharp” coercive mechanisms with “soft” elements in all aspects of social organization down to the micropolitics of citizens’ everyday life.

Never before have the Chinese people been as comprehensively administered as they are today, nor has any state mobilized so many resources to serve and control its people. Current trends in social governance combine digital surveillance with the revival of Mao-era human networks to oversee daily life.

At grassroots levels, the tasks of administrative units are being streamlined and expanded into the smallest social units – housing blocks, small private firms, families – and officials are expected to become more ideologically active and demonstrate party loyalty. Patriotic entrepreneurship is expected of business elites, and the Fengqiao experience calls on every official and cadre to mobilize, educate the masses and spread approved messages. Public service and social control now are nested within overlapping technological and administrative systems.

The combination of top-down party representation work on the private economy, and bottom-up recruitment of loyal citizens as the party’s agents, is working to create a wholly mobilized society. It is a system that depends on grassroots efforts and sustained provision of financial resources.

These trends and associated demands on local governance demand careful attention from international actors engaging with China to understand the domestic environment in which they operate and assess the country’s political resilience:

- An ever tighter embrace of the private sector economy means more party norms in corporate governance and strategic management. The trend is clear: all economic actors are asked to align with CCP political goals and to actively support Beijing’s development goals. In the struggle to establish China as a self-reliant superpower, entrepreneurs are being asked to ensure their firms prioritize patriotic entrepreneurship, not just profitability. Foreign companies, which already are evaluated on their usefulness for China, may face more onerous demands on their alignment with political goals and should watch for new informal political requirements.

- The impact on social governance is complicated as grid systems fuse responsiveness and social control. Social services and daily public administration are getting better and more locally relevant but can also be used to surveil and control. It remains to be seen how well this vast and expensive system can safeguard loyalty and stability among China’s citizenry. The key question is how long resources can be channeled into stability systems, given the pressing need for investment in public service and welfare provisions. Foreign observers should track signs of social discontent (including passive resistance and youth disengagement) and look out for visible strains on local governments (such as gaps in public service provision), as indicators of where the system is overextended.

- The push for ideological alignment signals more political repression: The party state is bringing increased focus and zeal to policing individual behavior and public discourse. Ethnic and religious minorities, liberal thinkers and civil rights advocates have long been at the receiving end of state repression. However, until recently average citizens were unlikely to come into conflict with authorities and be made a target of pressure for moral and ideological assimilation. Now, even passive failure to support the roadmap ahead and contribute is not seen as individual choice, but as a challenge to the CCP’s mandate – a dynamic that may ultimately cause backlash.

- External defensiveness and anti-Western narratives highlight the changing environment. Amid slowing economic growth, the CCP has made a partial strategic switch from improving quality of life as a source of legitimacy towards fostering patriotism, nationalism and defense readiness, all with strong anti-Western undertones. Amid the domestic setbacks, Chinese citizens can be partly won over through public campaigns and education reforms by an “us against the (Western) world” mentality. This means international actors are operating in a markedly different environment.

- Endnotes

1 | Jiang, Minjuan 蒋敏娟 (2023). “组建中央社会工作部与社会治理现代化” (Establishment of the Central Social Work Department and Modernization of Social Governance). People’s Forum 7, 49–52. https://archive. is/HmG42. Accessed: 30.04.2025.; The Paper (2023). “组建中央社会工作部,有何深意?” (What is the significance of establishing the Central Social Work Department?). April 25. https://archive.ph/q3MPJ. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

2 | Qiushi求是网 (2025). “读懂‘社会工作一定要加强’的深意” (Understanding the profound meaning of ‘social work must be strengthened’). March 10. https://archive.is/iyfts. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

3 | State Council (2025). “《新时代的中国国家安全》白皮书“ (White Paper ‘National Security in the new Era’).

May 12. https://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/zfbps_2279/202505/t20250512_894771.html. Accessed: 20.05.2025.4 | China Daily (2025). “Proposed laws on ethnic unity, economy praised.” March 9. https://archive.is/ QwRYm. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

5 | Grünberg, Nis and Katja Drinhausen (2019). “The Party leads on everything: China’s changing governance in Xi Jinping’s new era.” MERICS. https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/The%20 Party%20leads%20on%20everything_0.pdf. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

6 | For an in depth-analysis see e.g.: Møller Mulvad, Andreas (2019). “Xiism as a Hegemonic Project in the Making: Sino-Communist Ideology and the Political Economy of China’s Rise.” Review of International Studies 45(3): 449–470. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210518000530; Tsang, Steve and Olivia Cheung (2024). The Political Thought of Xi Jinping. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

7 | Zhang, Yang 张洋 and Zhao Cheng 赵成 (2024). “走在时代前列 领航复兴伟业 —— 习近平总书记引领新时代 党的建设新的伟大工程不断开创新局面” (Walking in the forefront of the times and leading the great cause of rejuvenation – General Secretary Xi Jinping continues to break new ground in leading the new great project of Party building in the new era). People’s Daily. July 1. https://archive.is/kQZ9U. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

8 | Organization Department of the Central Committee of the CCP (2024). “中国共产党党内统计公报” (Statistical Bulletin of the Communist Party of China). People’s Daily. July 1. https://archive.is/UhI4o. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

9 | China.Table (2024). “Ideology: Freedom of travel for Chinese citizens continues to be restricted.” October 8. https://table.media/en/china/feature/ideology-freedom-of-travel-for-chinese-citizens-continu-

es-to-be-restricted/. Accessed: 30.04.2025.10 | Antonio Gramsci defined the state as “… the entire complex of practical and theoretical activities by which the ruling class not only justifies and maintains its dominance, but manages to win the active consent of those over whom it rules …”, see Gramsci, Antonio (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. London: Lawrence and Wishart, p. 244.

11 | In party policy plans and government work reports statements on social governance are now often discussed in the context of national and public security work. One recent example is the inclusion social governance in the section on national security in the outcome document of the CCP’s 2024 Third Plenum. State Council (2024). “Resolution of CPC Central Committee on further deepening reform comprehensively to advance Chinese modernization.” Juli 21. https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202407/21/content_WS669d0255c6d0868f4e8e94f8.html. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

12 | Compare e.g., Pei, Minxin (2024). The Sentinel State: Surveillance and the Survival of Dictatorship in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.10860939. For an analysis of local implementation see Batke, Jessica and Mareike Ohlberg (2020). “State of Surveillance.” ChinaFile. October 3. https://www.chinafile.com/state-surveillance-china. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

13 | Batke, Jessica (2023). “Holding Sway.” ChinaFile. September 23. https://www.chinafile.com/repor- ting-opinion/features/united-front-work-department-domestic. Accessed: 30.04.2025; Joske, Alex (2019). “Reorganizing the United Front Work Department: New Structures for a New Era of Diaspora and Religious Affairs Work,” China Brief 19(9). https://jamestown.org/program/reorganizing-the- united-front-work-department-new-structures-for-a-new-era-of-diaspora-and-religious-affairs-work/. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

14 | Zhang, Feng 张峰 (2015). “习近平中央统战工作会议重要讲话的8个创新性亮点” (8 innovative highlights of Xi Jinping’s important speech at the Central United Front Work Conference). People.cn. June 6. https:// archive.is/eRD89. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

15 | State Council Bulletin (2023). “中共中央 国务院印发《党和国家机构改革方案》” (The Central Committee of the CCP and the State Council issued the ‘Plan for the Reform of Party and State Institutions’). March 16. https://archive.is/BZpjv. Accessed: 30.04.2025. While featuring a different institutional set up and responsibilities, the CCP has previously established and abolished a Society Affairs Work Department (1939-1949), which served predominantly for political and social control and was later absorbed into the new Ministry of State Security and internal intelligence apparatus.

16 | CNR (2023). “组建中央社会工作部,有何重要意义?” (What Is the Significant Importance of Establishing the Central Social Work Department?). March 17. https://archive.is/zL3Lm. Accessed: 30.04.2025; Zhang, Ke 张克 (2023). “从地方社工委到中央社会工作部:党的社会工作机构职能体系重塑” (From Local Society Work Committees to the Central Society Work Department: Restructuring the Functional System of the Party’s Society Work Institutions). Administrative Tribune 30(3): 72-81. https://link.oversea.cnki. net/doi/10.16637/j.cnki.23-1360/d.2023.03.003. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

17 | The Paper 澎湃 (2024). “全国31个省市自治区均已组建党委社会工作部门并开始全面履职” (All 31 Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions across the Country Have Set up Party Committees and Social Work Departments and Have Begun to Fully Perform Their Duties). February 23. https://archive.is/ AcU5u. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

18 | Zhang (2023).

19 | State Administration for Market Regulation (2023). “市场监管总局出台《市场监管部门开展小微企业个体工 商户专业市场党建工作指引》” (The State Administration for Market Regulation Issued the ‘Guidelines for Market Supervision Departments to Carry out Party Building Work in Specialized Markets for Small and Micro Enterprises and Individual Business Owners’). September 8. https://archive.is/BVY6k. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

20 | For further background on the Society Work Department also see Pieke, Frank N. (2025). “The Communist Party of China’s New Central Department of Social Work: Neo-Socialist Governance or Bolshevized Party Discipline?” Journal of Contemporary China: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2025.249 0744. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

21 | Wu, Hansheng 吴汉圣 (2024). “基层强则国家强 基层安则天下安” (If the grassroots are strong, the country will be strong; if the grassroots are safe, the world will be safe). Qiushi. May 16. https://archive.is/ Aek0J. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

22 | The Paper 澎湃 (2023). “组建中央社会工作部,有何深意?” (What is the significance of establishing the Central Social Work Department?). April 25. https://archive.ph/q3MPJ; Jiang, Minjuan 蒋敏娟 (2023). “ 组建中央社会工作部与社会治理现代化” (The Establishment of the Central Society Work Department and the Modernization of Social Governance). People’s Forum 7, 49–52. https://archive.is/HmG42. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

23 | Sadeler, Christina (2024). “Ahead of the Third Plenum, diverging visions for China’s private sector.” MERICS. July 12. https://merics.org/en/comment/ahead-third-plenum-diverging-visions-chinas-private-sector. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

24 | State Council (2017). “中共中央 国务院关于营造企业家健康成长环境弘扬优秀企业家精神更好发挥企业家作 用的意见” (Opinions of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council on creating a healthy growth environment for entrepreneurs, promoting excellent entrepreneurial spirit, and better leveraging the role of entrepreneurs). September 25. https://archive.is/LT74a. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

25 | State Council (2019). “中共中央 国务院关于营造更好发展环境支持民营企业改革发展的意见” (Opinions of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council on creating a better development environment to support the reform and development of private enterprises). December 22. https://archive.is/QHWbj. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

26 | General Office of the CCP Central Committee (2020). “中共中央办公厅印发《关于加强新时代民营经济统战工作的意见》” (The General Office of the CPC Central Committee issued the ‘Opinions on Strengthening the United Front Work in the Private Economy in the New Era’). September 15. https://archive.is/ nVLDW. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

27 | General Office of the CCP Central Committee (2019). “中共中央办公厅印发《关于加强和改进非公有制企业党的建设工作的意见(试行)》” (The General Office of the CCP Central Committee issued the ‘Opinions on Strengthening and Improving Party Building in Non-public Enterprises (Trial Implementation)’). February 15. https://archive.is/gzjYz. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

28 | Lau, Chris, Marc Stewart and Martha Zhou (2024). “‘Really Squeezed’: Why Drivers in the World’s Largest Food Delivery Market Are Having Meltdowns.” CNN Business. October 17. https://edition.cnn. com/2024/10/17/business/china-food-delivery-drivers-meltdowns-intl-hnk/index.html. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

29 | Chung, Ray and Lee Heung Yeung. Radio Free Asia (2024). “China Wants Its 12 Million Delivery Drivers to Work for the Party”. June 13. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/delivery-drivers-06132024152806.html. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

30 | Drinhausen, Katja and Helena Legarda (2022). “Comprehensive National Security’ unleashed: How Xi’s approach shapes China’s policies at home and abroad.” MERICS.https://merics.org/en/report/comprehensive-national-security-unleashed-how-xis-approach-shapes-chinas-policies-home-and. Accessed: 30.04.2025; Davidson, Helen (2024). “Love the army, defend the motherland: how China is pushing military education on children” The Guardian. August 11. https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/aug/11/love-the-army-defend-the-motherland-how-china-is-pushing-military-education-on-children. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

31 | Bandurski, David (2021). “Red Genes.” China Media Project. May 18. https://chinamediaproject.org/ the_ccp_dictionary/red-genes/. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

32 | Ma, Josephine and Echo Xie (2021). “China opens more research centres dedicated to Xi Jinping Thought.” . South China Morning Post. July 9. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3140381/china-opens-more-research-centres-dedicated-xi-jinping-thought. Accessed: 30.04.2025; Zhuang, Sylvie (2023). “National Security Studies Are Going Mainstream in China. Will It Breed a New Chinese Elite?” South China Morning Post. December 2. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3243616/national-security-studies-are-going-mainstream-china-will-it-breed-new-chinese-elite. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

33 | Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2024). “Chinese vice premier calls for promoting spirit of scientists.” May 26. https://archive.is/tlSai. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

34 | In addition to the annual National Security Day established in 2025 and related-campaigns, districts, residential communities, schools and even companies increasingly organize defense education and training (国防教育). See e.g. The People’s Government of Xinglongtai District (2025). “光明社区开展“ 强国复兴有我”青少年国防教育知识讲座活动” (Guangming community carries out “the rejuvenation of the strong country and I” youth defense education lecture). February 27. https://web.archive.org/ web/20250512075531/https://www.xlt.gov.cn/2025_02/27_15/content-510416.html. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

35 | Bloomberg News (2023). “China’s Spy Agency Takes to WeChat in Espionage Crackdown.” August 1. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-02/china-s-spy-agency-takes-to-wechat-in-espionage-crackdown?leadSource=uverify%20wall. Accessed: 30.04.2025; Greitens, Sheena Chestnut (2025). “Counter-Espionage and State Security: The Changing Role of China’s Ministry of State Security.” China Leadership Monitor 83. https://www.prcleader.org/post/counter-espionage-and-state-security-the-changing-role-of-china-s-ministry-of-state-security. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

36 | Pei, Minxin (2021). “Grid Management: China’s Latest Institutional Tool of Social Control.” China Leadership Monitor 67. https://www.prcleader.org/post/counter-espionage-and-state-security-the-changing-role-of-china-s-ministry-of-state-security.

37 | Buckley, Chris, Vivian Wang and Keith Bradsher (2022). “Living by the Code: In China, Covid-Era Controls May Outlast the Virus.” New York Times. January 30. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/30/ world/asia/covid-restrictions-china-lockdown.html.

38 | Jean Christopher Mittelstaedt (2021). “The grid management system in contemporary China:

Grass-roots governance in social surveillance and service provision.” China Information 36(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X211011565. Accessed: 30.04.2025.39 | Summary based on Chinese language media reports and job descriptions for grid worker positions. Zhihu (2023). “什么是街道网格员,待遇怎么样? ” (What is a street grid worker and how is he paid?). March 8. https://www.zhihu.com/question/321193626. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

40 | aistudy.baidu.com (2024). “网格员是做什么的工资待遇” (What is the salary of a grid worker?). Decem-

ber 16. https://archive.is/MvgG7. Accessed: 30.04.2025.41 | Extrapolating from one locality can only provide an approximation of the resources that go into the system, as numbers of grid workers per resident and salary ranges vary across China. Shunyi was selected for being a successful model grid system that covers both urban residential areas and more rural communities. Using the Shenzhen example as a baseline would result in even higher numbers, whereas rural areas are much less well-paid.

42 | State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2025). “Full text: Report on the Work of the Government.” March 12. https://archive.is/CFWMu. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

43 | Communist Party Member Network (2023). “新时代的‘枫桥经验’” (The ‘Fengqiao Experience’ of the New Era). November 6. https://archive.is/hg4QZ. Accessed: 30.04.2025; China Media Project (2021). “Fengqiao Experience.” April 16. https://chinamediaproject.org/the_ccp_dictionary/fengqiao-experience/. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

44 | Wan, Jianwu 万建武 (2023). “‘枫桥经验’: ‘中国之治’的一张金名片” (‘Fengqiao experience’: A Golden Calling Card of ‘Chinese Governance’). Qiushi. December 1. https://archive.is/H5gzM. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

45 | Ministry of Public Security of the People’s Republic of China (2019). “公安部作出决定 命名首批100个‘枫桥式公安派出所’” (The Ministry of Public Security has decided to name the first batch of 100 ‘Fengqiao-style police stations’). November 29. https://archive.is/qsJIw. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

46 | State Council (2022). “中共中央 国务院关于做好2022年全面推进乡村振兴重点工作的意见” (Opinions of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council on comprehensively promoting key tasks of rural revitalization in 2022). February 22. https://archive.is/aXilK. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

47 | Descriptions of daily hardships and complaints can be found in Chinese language news articles and social media posts of grid worker. An example of deadly violence against a female grid worker as well as a detailed insight into work conditions can be found in a news article on the case: Sanlian Life Weekly (2024). “一名25岁大学生之死” (Death of a 25-year-old college student). https://archive.is/PkXGn. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

48 | Gong, Weibin 龚维斌 (2025). “习近平总书记关于推进国家治理体系和治理能力现代化的重要论述的原创性贡献” (The original contribution of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important exposition on promoting the modernization of the national governance system and governance capacity). People.cn. February 13. https://archive.is/lVPFc. Accessed: 30.04.2025.

49 | State Council (2025).

This MERICS Report is part of the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.