Wirtschaftlicher Druck belastet Chinas Ambitionen

No. 2, July 2022

What you need to know: It’s shaping up to be a tough year for China Inc. both at home, and abroad

The economic stress China currently experiences at home has repercussions for China Inc., the often-coordinated network of companies, financiers, and officials expanding China’s footprint abroad.

First, China’s supply chain woes are quickly becoming the world’s problem too. With ‘the world’s factory’ in disarray, any companies or individual consumers awaiting goods shipments from China are in for delays and shortages – the last thing many countries need at a time of rising inflation. Many of China Inc.’s projects within the Belt and Road (BRI) are likely to suffer delays and temporary setbacks too because of supply disruptions from the home market, and possibly even backtracking on projects overseas as aggressive stimulus is called for back home.

Second, China’s annual outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) flows were already struggling to recover throughout 2021, in sharp contrast to a massive resurgence in global FDI flows which rose 77 percent year-on-year. Instead, as MERICS and Rhodium reported in April, China’s outbound non-financial investment rose by a meagre 3 percent in 2021 to USD 114 billion (EUR 96 billion). The lack of a recovery was attributed to the zero-Covid strategy, which “hindered cross-border travel and deal-making activities.” The Omicron outbreaks mean China Inc. looks increasingly unlikely to get back into major investing abroad in 2022.

Third, Beijing’s continued intransigence on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could harm perceptions of China Inc.’s global presence at least in some parts of the world. For now, Beijing seems capable of holding together the BRICS coalition as a platform for its global power projection. Shifting domestic politics in key BRI partner countries such as Brazil and Kenya in 2022 and with doubts about the role Beijing plays in the looming global food crisis, the outlook for China’s global expansion looks more uncertain.

Against this background, this edition of the Global China Inc. Tracker provides you with critical insights into China’s evolving ties with one of the BRICS countries, Brazil, and China’s radical food security strategy.

Jacob Mardell, freshly back from that very country, covers Brazil in this quarter’s Regional Spotlight. Sino-Brazilian ties have been a mixed bag under Bolsonaro’s leadership, balanced between his refusal to join the BRI on one side and China’s growing investments in Brazil as a supplier of soybeans, iron ore, and crude oil. The October election between Bolsonaro and his more China-friendly rival, Lula, will determine the future prospects for this member of the BRICS.

Aya Adachi and Jacob Gunter explore the role of this edition’s Key Player: COFCO – As China’s chief food processor and distributor, at home and abroad, COFCO has a key role in Beijing’s food security strategy. As the war in Ukraine threatens global food security, we look into China’s food production and trade, and what sort of international role it might play in a food supply or price crisis.

Regional spotlight: Brazil

Brazil is by far the largest country in Latin America, with roughly half of South America’s landmass, population, and GDP. As such, it is a key regional partner for both China and the EU.

China’s ascent up the value chain has increased the degree of export competition between China and Europe in Latin America, as it has elsewhere on the planet. Brazil is of special importance to transatlantic interests largely because of its dual identity as a large “Western” country and a developing country in the “Global South.” Furthermore, there is potential for much closer ties with China should former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva win back power in this year’s general election.

Though technically a multi-candidate race, the October election is really a divisive showdown between two political giants: the incumbent right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro and his arch-nemesis Lula, a former two-term president and founding member of the Brazilian Worker’s Party (PT).

Brazil is not officially part of China’s BRI – it remains one of only a few dozen developing countries that have not yet signed a memorandum of understanding with Beijing on jointly building the BRI. Reluctant to be seen as aligning with China against the United States, Brasilia has adopted a “wait and see” approach to the BRI, though analysts predict that if Lula wins in October, he will follow Argentina’s lead and join it.

Brazil may be able to win some concessions in return for its signature, but the move will have more political than economic relevance.

There is a correlation in Brazil between left-leaning political sentiments and more China-friendly instincts on the one hand, and between right-wing, US-friendly rhetoric on the other. The left identifies more willingly with Brazil’s Global South identity than does the right.

Lula and Bolsonaro reflect this dichotomy. Lula‘s presidency coincided with the birth of the BRICS acronym (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and he oversaw the boom in Sino-Brazilian ties: Bolsonaro warned of China “buying Brazil” in his 2018 campaign, and voiced Sinophobic conspiracy theories about Covid.

Nonetheless, the right’s anti-China rhetoric has not damaged the economic relationship. Brazil and China are too important to one another for their commercial ties to be derailed by politics. Their ties are underwritten by pragmatism, profit, and economic complementarities.

Trade drives Sino-Brazilian ties, specifically exports to China of three raw materials – unprocessed soybeans, iron ore, and crude oil. For Brazil, China is an important source of export revenue and crucial to its agroindustry. But dependency flows both ways.

In 2020, Brazil was China’s sixth largest source of imports overall, its fifth for crude oil, second for iron, and first for soybeans. Brazil grows 55.9 percent of China’s soy – most of it destined for animal feedstock and thus vital to China’s food security. The United States is the only other notable source of soybeans for China, so Brazil is important in the context of US-China tensions and rising food prices. Brazil is also a more politically trustworthy source of iron ore than China’s top provider, Australia.

Beyond a few specific sectors, Chinese investment is less significant, though still characterized by the same commercial logic and complementarity. For instance, China Three Gorges and State Grid have 48 percent and 60 percent of their foreign holdings in Brazil respectively. Lured by Brazil’s massive energy market, State Grid entered the Brazilian market in 2010 by buying seven power firms for USD 1 billion. It has since leveraged its financial muscle to acquire the Brazilian assets of several European power companies and has deployed ultra-high voltage technology to tackle transmission problems common to both China and Brazil. Chinese companies continue to expand their presence by buying Brazilian renewable energy assets. Lately, greenfield investments that tap into the northeast’s huge solar and wind potential have become popular.

The pivotal role of Chinese institutions in the Brazilian oil sector tells a similar story of comparative advantage. In 2006, state oil firm Petrobras discovered colossal pre-salt oil reserves off the Brazilian coast. Wanting to balance European and US interests, Brazil turned to China, whose institutions have been adept at offering loans in times of political crisis and economic turmoil, when other funding was less available. In return, Beijing has secured important strategic supplies and a lucrative role for China National Petroleum Corporation as a service and equipment provider.

Chinese companies have had less success in agriculture. Agricultural giant COFCO, (profiled below), has carved out a small place alongside the European and US agribusinesses that dominate Brazil’s soybean harvest. COFCO’s early attempts to buy land were stymied by public opposition, and Chinese involvement has remained minimal.

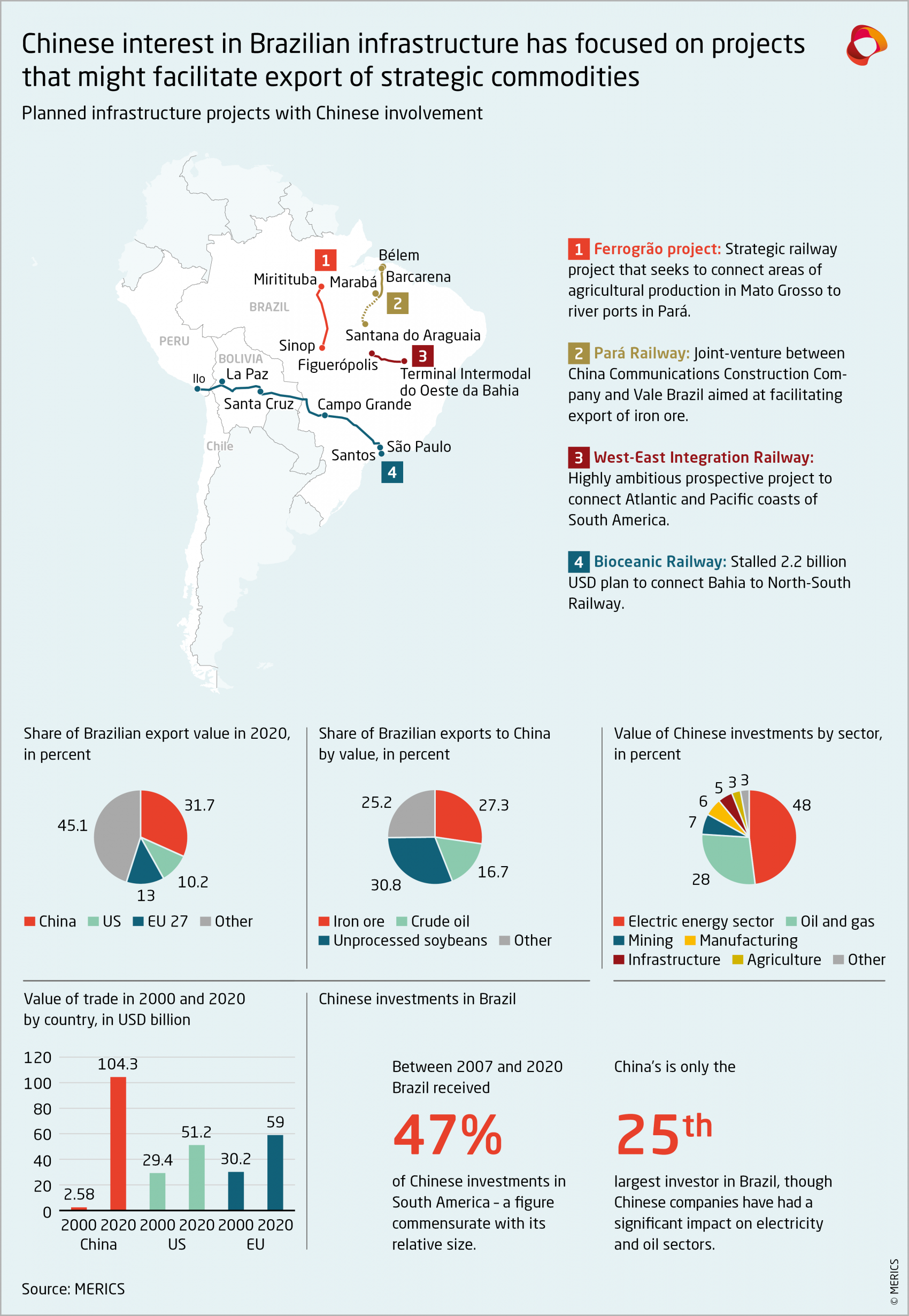

Infrastructure cooperation between China and Brazil has also remained limited. Brazil’s spending is too low to maintain its current assets. The rail sector is especially neglected, ever since policy decisions in favor of automobiles in the 1950s and 60s. Brazil is now hampered by ageing, inefficient road infrastructure at odds with its export economy. Every year, Brazil loses an estimated 3 percent of its soybean harvest off the back of trucks.

Given the size of Brazil’s economy, its chronic infrastructure deficit, and Beijing’s tendency toward flagship infrastructure projects, it would have been reasonable to expect a frenzy of Chinese-sponsored infrastructure construction. But Chinese infrastructure projects have been few and far between. Proposals have focused on facilitating Brazilian exports, but even much-needed, mutually-beneficial rail projects have made little progress.

Keeping out of the "BRI family” is unlikely to be the reason behind Brazil’s disappointing progress on this front. An incredibly difficult regulatory environment and tangled bureaucracy complicates infrastructure projects for all involved. A 2017 World Bank study blamed the mismatch between complex legal requirements and poor technical capacity; 46 percent of the projects it analyzed were delayed, and 16 percent suspended before completion.

Lula’s re-election and joining the BRI will not fix these problems, but a refocusing of political will on cooperation with China may help.

Although politics has not derailed Sino-Brazilian ties, there is a strong sense among analysts in Brazil that the relationship is stagnant. The most common criticism of Brazil’s China policy is that there isn’t one. If Lula wins re-election, he will bring an interest in China - and foreign policy more generally - that has been absent for some time.

The circumstances of a third Lula presidency would be very different to his first two terms, when the commodity boom, a successful Olympics bid, and other international factors helped catapult Brazil onto the international stage. Still, observers can’t help but contrast the image of Bolsonaro dining alone at Davos with that of the man Barack Obama once called the “most popular guy on earth.”

There are several potential synergies between China and Brazil, should deeper cooperation be on the agenda. As the planet’s most biodiverse country and home to 12 percent of global forest cover, Brazil holds unrealized potential as an ecological superpower. This, alongside abundant renewable energy resources, makes it a perfect partner for China’s “Green Silk Road” ambitions. Huawei’s win in last year’s 5G auction also made clear that Brazil is participating in China’s digital agenda. There is wide enthusiasm for greater tech cooperation with China, which fits Beijing’s ambitions to take the BRI in a “high-quality” direction.

In May, China’s foreign minister Wang Yi announced that Beijing was seeking to expand the BRICS grouping, implicitly as a challenge to NATO and the G7. If Lula is re-elected, he is likely to embrace Global South ties and throw his weight behind the BRICS grouping. Given the growing tensions between transatlantic and Chinese interests, it is ever more important for Europe to heed the balancing role of China’s strategic partners in the Global South.

Key player: China’s food giant, COFCO, and its contribution to China’s radical food security strategy

Russia’s invasion has drastically impacted Ukraine’s ability to produce and export grain to the world. Ukraine, a major global bread basket, has only been able to plant 7 million hectares of the 15 million it had planned to grow this year. Add to this Russia’s blockade and mining of Ukraine’s ports. People in Africa and the Middle East are projected to face serious food shortages soon. Lost supply will bring higher overall global commodity prices, on top of rises due to pandemic-induced shortages. The potential for a food crisis, driven by supply or price issues, looms over the developing world. In anticipation of this global storm, the EU urged China to release enough grain from its strategic reserves to offset supply and price problems, raising the issue at the 2022 EU China Summit.

To better understand China’s position within global food markets and its potential role in a global food crisis, it necessary to understand COFCO – China’s primary state-owned food trader and distributor, at home and globally – and second, China’s food security strategy. The latter may make it difficult to convince Beijing to open its own grain reserves to alleviate a crisis.

COFCO Group (China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation)

COFCO plays a major role in executing Beijing’s policy agenda. In conjunction with the party-state, COFCO contributes to China’s food security strategy, chiefly through stabilizing supplies and market prices for commodities and countering any local shortfalls through imports.

COFCO, China’s largest food company, is one of the SASAC-97, the 97 major state-owned enterprises under the control of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission. COFCO owns a wide range domestic subsidiaries for the trading, processing, and distribution of China’s agricultural and food products – from grains and oils in the agricultural heartlands, to cotton and tomatoes in Xinjiang, and consumer brands like Great Wall wine and Mengniu dairy.

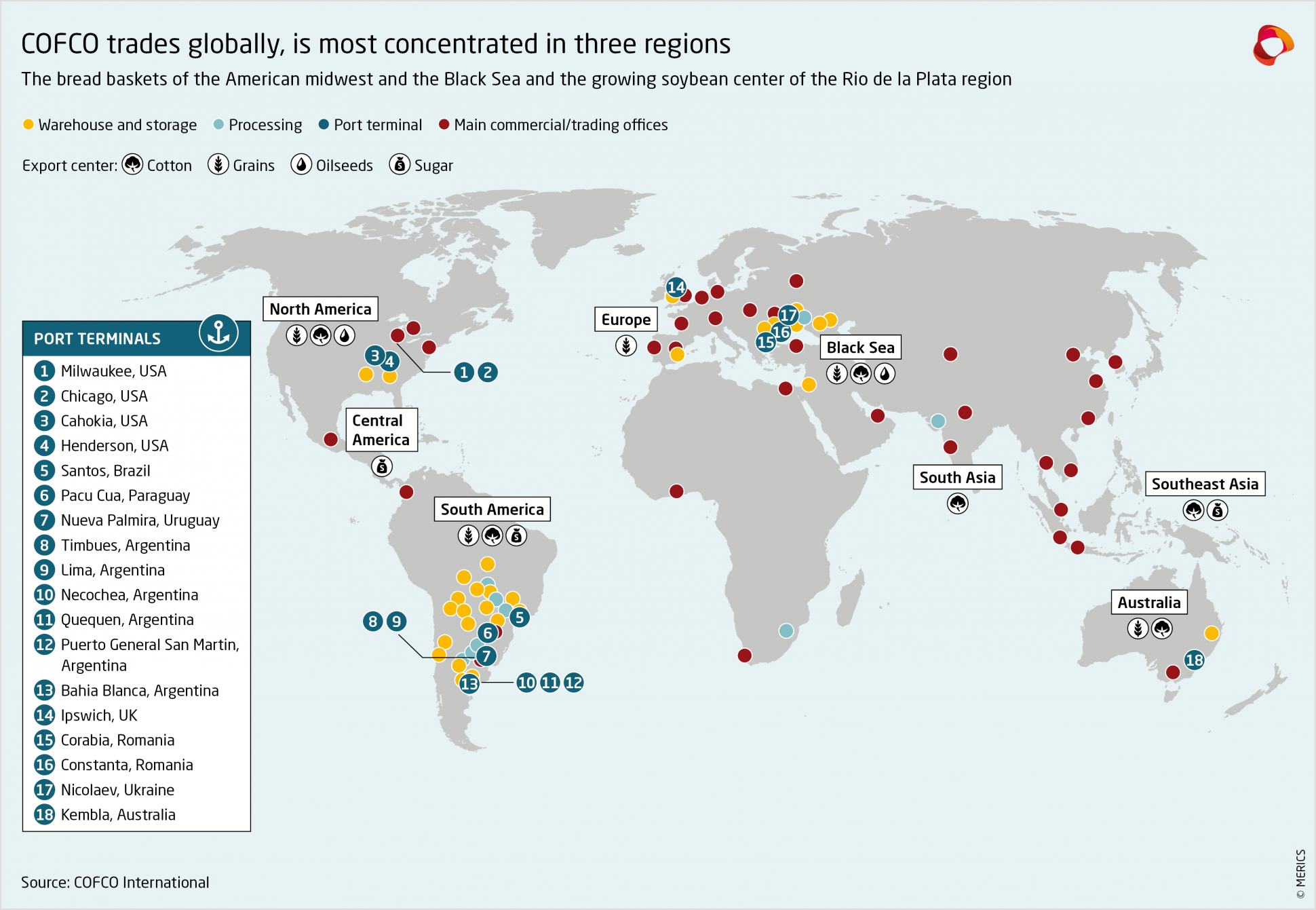

COFCO also holds significant assets overseas through its chief global subsidiary – COFCO International. It has a presence on every continent, with a strong focus on major food exporting regions like South America and the Black Sea region. Its operating profile differs from the other major agribusinesses collectively known as the ‘ABCD’ (ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Dreyfus), which have truly global networks buying and selling within a huge range of world markets. COFCO International focuses mainly on directing food back towards China, and even advertises itself as a business partner with “unique direct access to a growing Chinese market”. Focused on warehouse and storage, processing, trading and shipping, it trades in a range of agricultural goods, but is chiefly in the markets of key foodstuffs like grain, sugar, coffee, and soybeans.

COFCO, China Inc., and Beijing’s extreme approach to food security

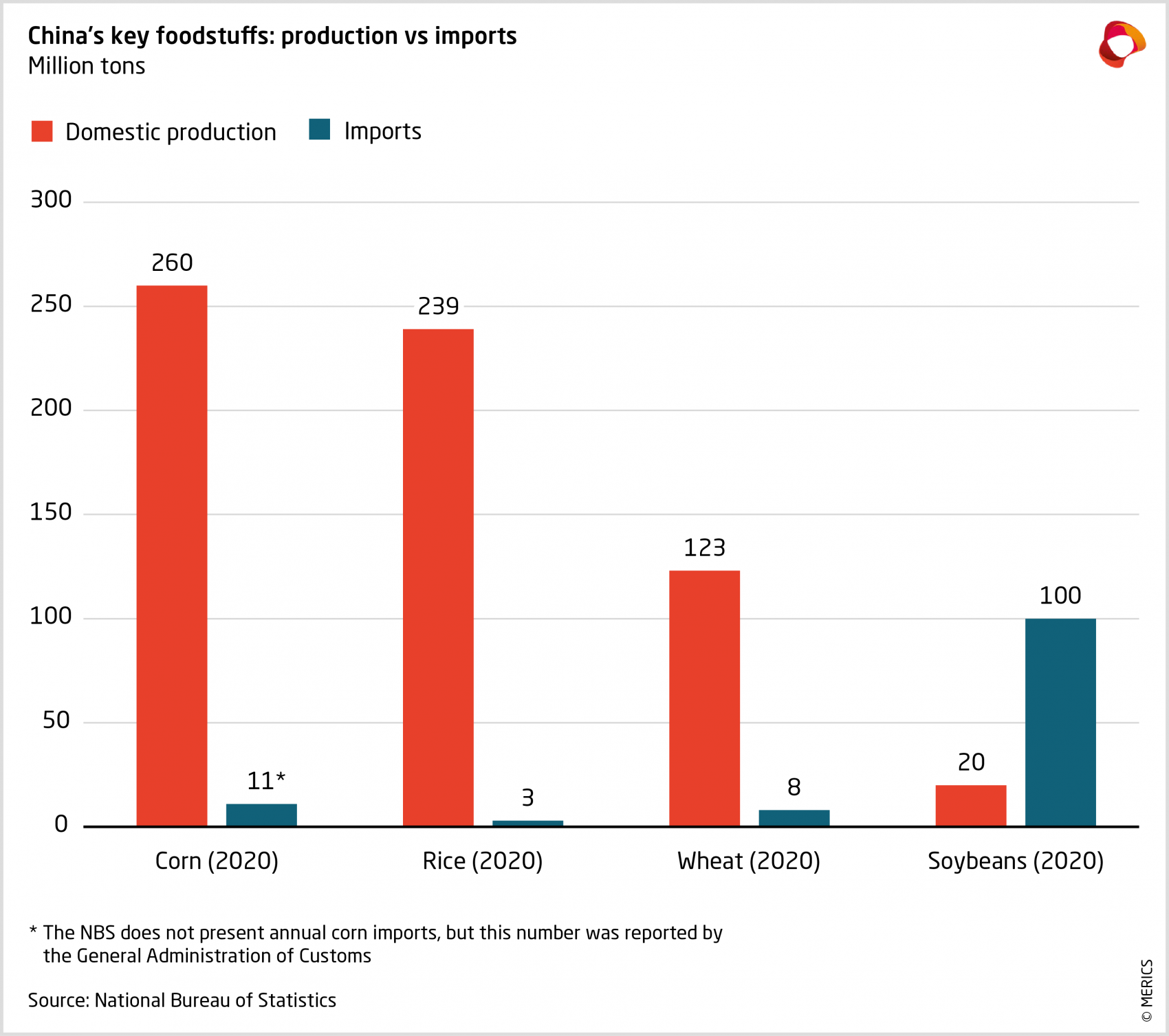

China has a radical food security strategy, evident in massive state-run grain reserves – their size is a state secret, but estimates put them at roughly 69 percent of total global reserves of corn; 60 percent of rice; and 51 percent of wheat. With the Great Famine of 1959-1961 within living memory, food security remains a sensitive issue in China. The 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025) aims include greater output through agricultural and rural modernization and supply guarantees for grain and other foodstuffs.

China has a long-standing target of 95 percent self-sufficiency in key grain production, and needs few imports for food security. Supply is achieved through a mix of protectionism and stabilizing factors. Imports are highly restricted through a tariff rate quota system, which allows importation of just enough grain to reach domestic consumption levels at duties as low as 1 percent. Once quotas are reached, tariffs rise up to 65 percent, making imports cost-prohibitive and thereby protecting domestic producers. Within this protected market, subsidies help regulate prices, as does COFCO through its dominant position in key foodstuff processing and distribution.

Finally, COFCO plays a key role in what limited foodstuff imports exist – notably grain from Ukraine and Russia, and US and Brazilian soybeans. COFCO has become an increasingly important part of China’s food strategy as China has shifted from being a net exporter of food to a net importer. Although food security is assured through domestic grain production and reserves, China’s growing appetite for meat has led to a surge in soybean imports for feedstock.

China Inc.’s position and role in the threatened food crisis

China does not face any immediate risk to its food security from the conflict in Ukraine. In the short term, the government is likely to make small domestic adjustments to mitigate domestic impacts. In March 2022, China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the Ministry of Finance announced plans to increase soybean production, currently China’s top agricultural import.

However, China could play a significant role in mitigating the risk of a global food crisis through decisions on food purchases and the use of its grain reserves. Whether it will is another matter.

For Beijing to help offset higher food prices in the developing world, it could expand its donations to the World Food Programme and other food aid schemes. This would have a financial cost but leave its own food security position unaffected.

However, Beijing is likely to be cautious about using its reserves to stabilize global food prices due to the sensitivities surrounding domestic food security. Such a move is unlikely, given the risk of a backlash from a public with living memory of famine and starvation – something the CCP cannot afford when citizens are already frustrated by extensive Covid lockdowns (including food distribution issues).

However, Beijing may decide to change its food import strategy if a global food crisis emerges. If grain imports maintain their trajectory of the past decade, global commodity prices could rise, hurting China’s reputation in developing countries. China’s self-image as a generous contributor to South-South cooperation would suffer. Instead, Beijing could temporarily pause its stockpile expansion to mitigate rising global food prices – a low key approach that avoids making things worse or risking domestic legitimacy may be the safest.

Yet, China does have impending risks to its domestic food security. Soil exhaustion, pollution, and rising problems with fresh water resources, mean China's total arable land had fallen to 1.28 million sq km by the end of 2019, down nearly 6 percent from 2009 . Meanwhile, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) has estimated that urbanization and an ageing rural workforce could bring a grain supply gap of about 130 million tons by the end of 2025 (SCMP). Beijing may well decide that it must continue expanding imports and reserves for China’s own future food security, even at the expense of global food supplies and prices at a time of crisis.

Whatever Beijing decides, its role in global food markets could have considerable impacts for the developing world, for better or for worse.

Global China Inc. Updates

BRI POLITICS

China’s deal with the Solomon Islands creates security concerns for Australia and New Zealand

The PRC finalized a security deal with the Solomon Islands in an unwelcome surprise for Pacific neighbors Australia and New Zealand. The deal is believed to offer the chance for Chinese warships to be based and refueled in the archipelago. China also wooed the Pacific nation of Kiribati, which switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC in 2019. Foreign minister Wang Yi visited in May on his eight nation Pacific tour in May. China’s longstanding dedication of political and economic resources to the region has started to pay off. Beijing has been able to expand its influence into the South Pacific partly due to the relative absence of the US and its Pacific allies. However, that may change. The US and New Zealand responded to the security deal with a joint statement about strengthening security cooperation in the region – a big step for Wellington – which was met with aggravation in Beijing.

DIGITAL, HEALTH, AND TECH

China’s Digital Silk Road advances in Bangladesh

China Railway International Group signed a contract for digital infrastructure with the Bangladesh government in April. Under the “Bangladesh National Digital Unicom” project, CRIG will construct 10,000 computer labs across the country, help to improve government statistics gathering techniques and technology, and build an information and communications literacy training center in the capital, Dhaka. It is the first major Digital Silk Road project in Bangladesh and typical of how China hopes to meet the Global South’s demand for digitalization. Chinese firms are all too happy to fulfill that demand, especially in the absence of meaningful competition from the West.

Huawei an increasingly central player in mobile payments in Africa

The popular Kenyan mobile payment service M-Pesa runs on Huawei Mobile, which each year processes billions of dollars in transactions. Moreover, Huawei Mobile Money is also powering similar mobile payment systems in other African countries, including Ghana, Angola, and Ethiopia.

The expansion in Chinese mobile payments , despite a reduction in Chinese investment in Africa, shows the demand-led resilience of China’s digital engagement in Africa.

ENERGY

China’s SOEs still backing overseas coal plants in Pakistan, Indonesia and Laos

China has shown its continued support for Pakistan through more BRI investment commitments, despite the recent chaotic change in government. PowerChina has obtained a contract to build a water supply project supporting the Thar coal plants, the biggest in Pakistan. Meanwhile, Energy China has won two new contracts in Indonesia and Laos in the coal power sector. While they cannot be classified as direct investments – technically restricted since President Xi’s UN pledge – the projects will support the construction and maintenance of coal plants through equipment and essential “engineering and technology services.”

Brazilian offshore oilfield tapped by Chinese SOE as part of larger international project

China National Offshore Oil Corp (CNOOC)'s ultra-deepwater pre-salt oilfield in Brazil was put into operation in May, the latest effort by the country's top offshore oil and gas producer to step up overseas oil and gas production. The oilfield is located in the Santos Basin and is part of an international cooperative project in which CNOOC currently holds a 9.65 percent working interest.

Myanmar dissolves business ties with Chinese solar power companies

The Myanmar government has cancelled 26 tenders for solar PV projects issued under the previous NLD government in September 2020. Chinese companies have dominated tenders for solar projects in Myanmar for several years, winning 28 of the 29 tenders offered between May and Sept 2020. Many of those companies have now been blacklisted for “breaching tender regulations.” They include three major private companies, Sungrow Power, Xi’an LONGi Solar and GCL System Integration, as well as three state owned power sector investors, Yunnan International Power Investment (a subsidiary of the State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC)), China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC), and the Gezhouba Group Overseas Investment Company.

MANUFACTURING, CONSTRUCTION, AND RESOURCES

New iron mine in Cameroon set to help Beijing diversify supplies for its steel industry

China’s Sinosteel Corp signed a USD 690 million contract for an iron ore mine in southern Cameroon.

Sinosteel signed a 50-year contract with the central African government to exploit the Lobe deposit. The move may be understood via the current uncertainty surrounding global commodity markets, as Chinese companies seek alternatives to Australian ore.

Growing appetite for Lithium in China drives new joint venture in Zimbabwe

China's Sinomine Resource Group Co. and Shenzhen Chengxin Lithium Group Co. agreed to set up a joint venture in Zimbabwe for cooperation on lithium mining projects. The joint venture will be registered in Harare, Zimbabwe with starting capital of USD 5 million, and carry out exploration on lithium and platinum mines. Global demand for lithium products – such as electric vehicle batteries – continues to rise. Chinese firms have accrued a substantial market share of the world’s critical raw materials for such technologies.

Guinea taps China to build stadium for upcoming African Cup of Nations 2025 tournament

China Construction Fifth Engineering Division Corp signed a RMB 1.99 billion EPC contract to build a 40,000-seat football stadium in Guinea’s capital, Conakry, for the 2025 African Cup of Nations. The stadium complex will include six training facilities and a smaller 17,000-seater stadium will be restored. Construction is due to be completed within 24 months.

Hungary set to be part of China’s NEV supply chain investments in Europe

GEM Co., Ltd., a Chinese company focused on waste recycling recently signed a memorandum of cooperation (MoC) with the Hungarian consulate in Shanghai for production of high nickel precursors for new energy vehicles (NEVs) and recycling scrapped power batteries in Hungary.

TRADE AND FINANCE

New airport terminal in Ethiopia begins construction, despite ongoing civil war

PowerChina began construction of a new airport terminal in Bahir Dar, the capital city of the Amhara region in northern Ethiopia, on 17 May. Ethiopia’s civil war, which has already claimed around 500,000 lives, has not slowed Chinese investment there. PowerChina’s deal followed CAMC Engineering’s signing of a contract to operate a sugar factory in Amhara on 10 May.

TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS

The ‘Eurasian Land-bridge’ sees traffic plummet due to Russian invasion of Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has all but halted traffic on one of the signature BRI projects: the China-Europe Railway Express (CERP). Practically all traffic passing through Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus has been stopped or diverted, and the volume of goods transiting by rail has dropped to decades-low levels. Moreover, the situation is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, leaving Chinese exporters wondering how to shift their exports to the already log-jammed freight sector.