China Overcapacities Monitor

China Overcapacities Monitor

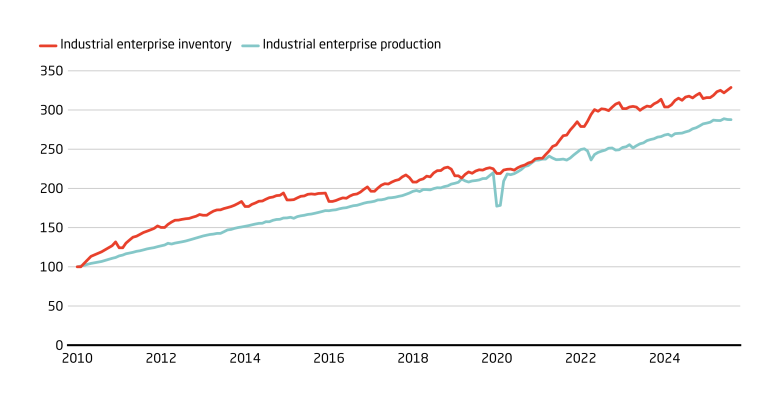

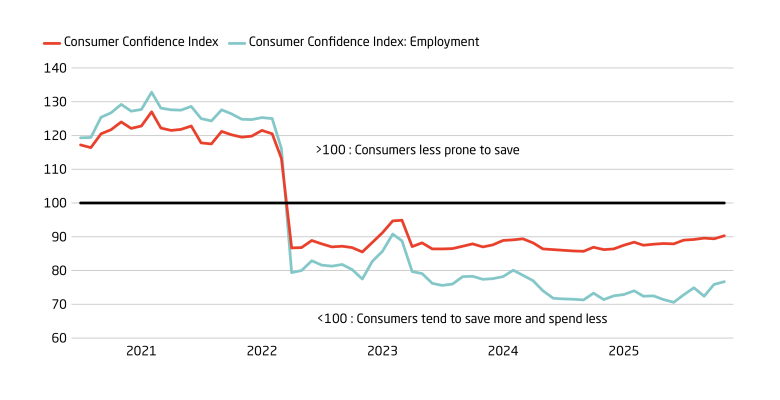

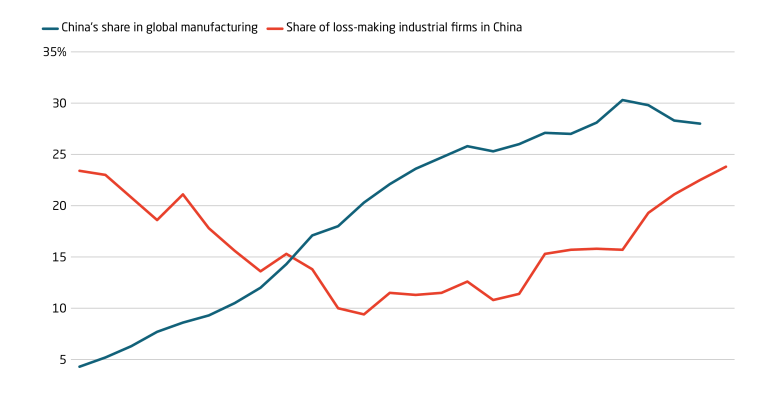

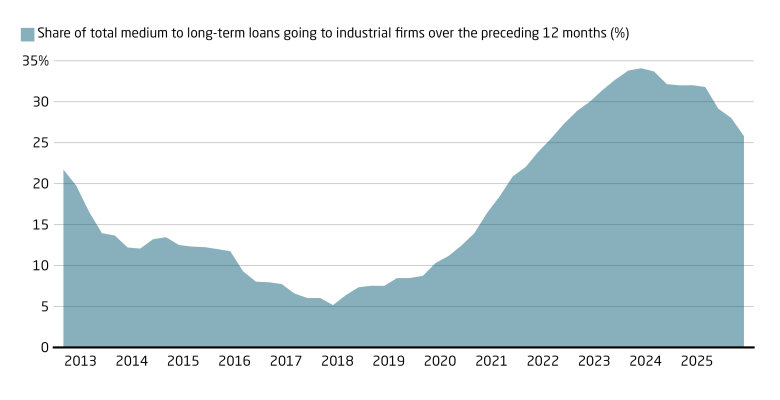

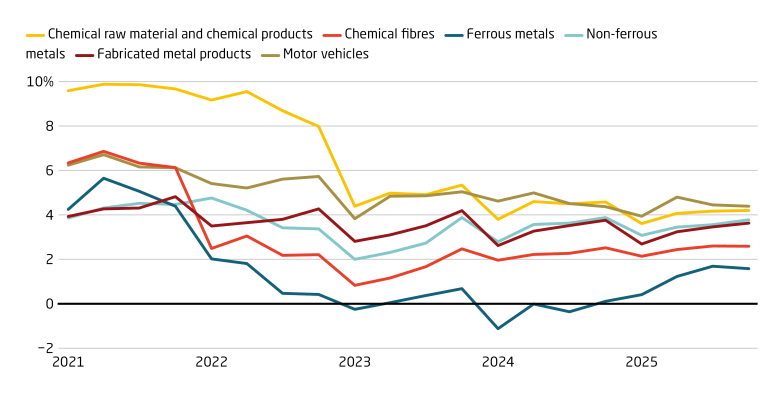

China’s industrial overcapacity is showing up first at home, then abroad. Investment in priority manufacturing remains high despite weak demand, pushing down prices, compressing margins, and raising the share of loss-making firms. Credit support and local government incentives often keep excess capacity in place.

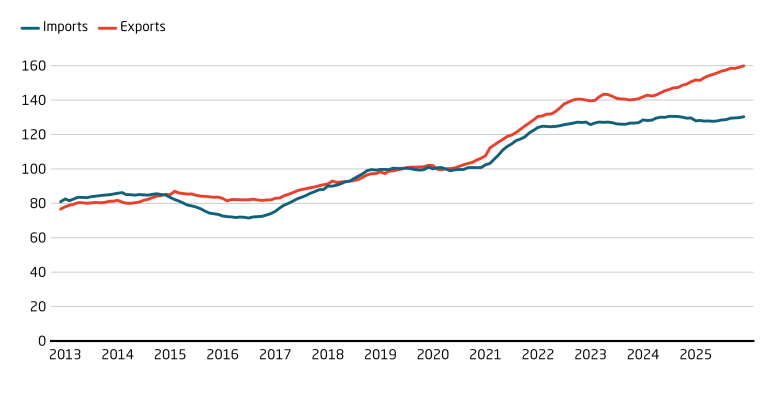

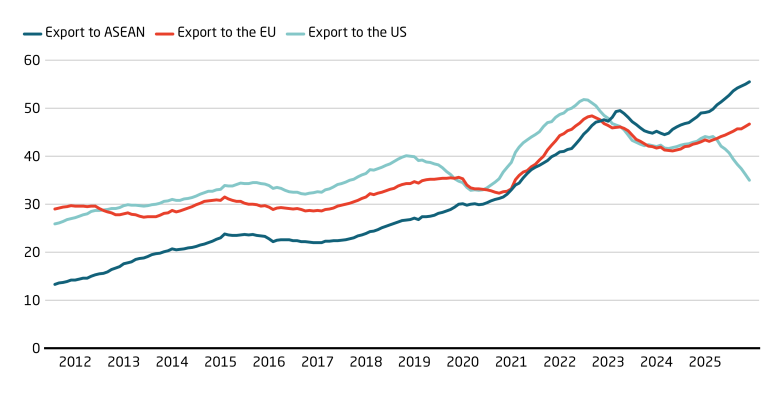

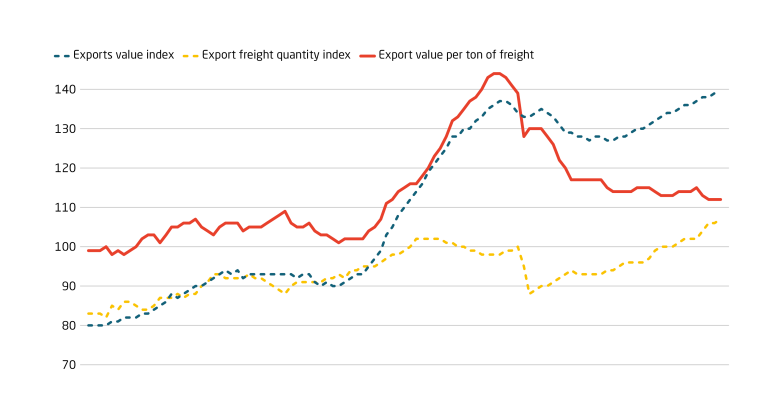

Short of domestic buyers, producers increasingly rely on exports to sustain output, reshaping the industry landscape worldwide. China’s continuously widening trade surplus shifts pressure onto external markets. With reduced access to the US, China has redirected trade flows to more open markets, including ASEAN and the EU.

This Monitor tracks these dynamics across sectors. It is designed to help policymakers and businesses monitor where price pressure is building, which sectors are most exposed, and how trade patterns are changing. Along with the analyses that will accompany each update, readers can select a graphic to open the related explanation.

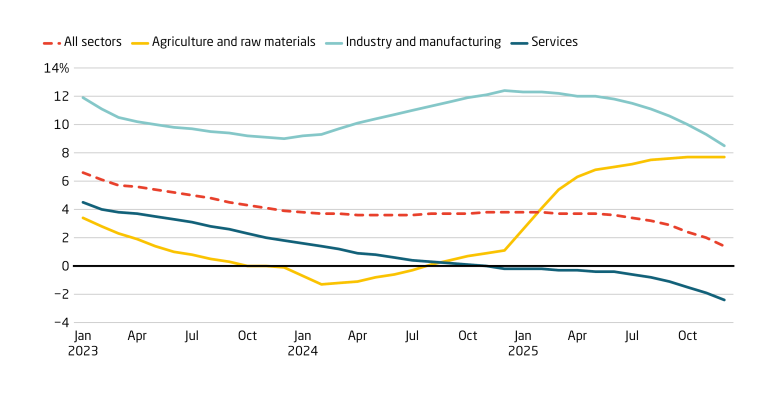

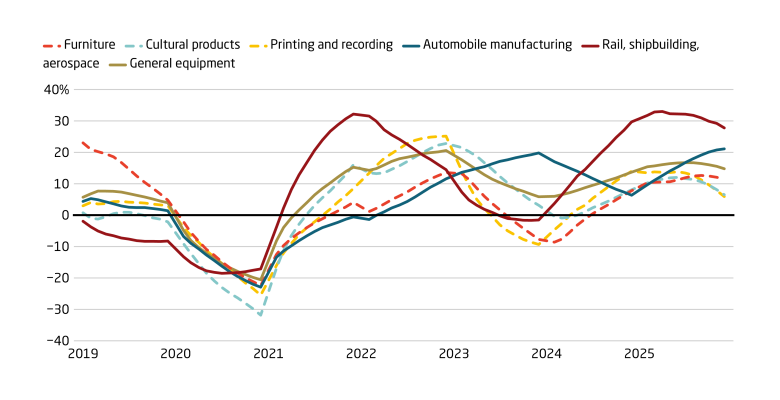

Evolution of investments

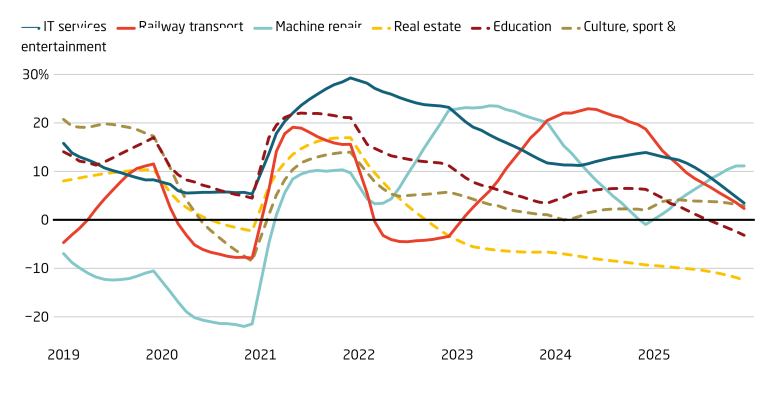

Capacity growth and consumption

Impact on companies’ profits and losses

Export of overcapacities

Authors