China's domestic debates under the shadow of geopolitics

How views about the economy, commercial culture, and trending topics reveal self-perceptions

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

This analysis is part of “China Spektrum,” a joint research project with the China Institute of the University of Trier (CIUT) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. As part of this project, we analyze expert and public debates in China. Learn more about the project and find previous publications here.

Key findings

This year’s China Spektrum report consists of two debate analyses and one quantitative media analysis. One debate follows an internal economic issue that has external consequences, known as economic “involution”. The other debate looks at why some of China’s commercial cultural exports are gaining global traction now. Finally, an analysis of trending news headlines from China’s largest online news aggregator reveals which foreign countries most prominently feature in the headlines of Chinese media and how that has changed since last year. Together, they show that even though censorship of Chinese netizens is pervasive on its domestic internet, especially around sensitive political events, online debates endure, nevertheless. The persistence and richness of these debates highlight the importance of paying close attention to them.

On economic “involution”:

- “Involution”, the disruptive impact of overproduction and relentless price cuts, has been taking place amid ongoing US-China trade tensions. Experts offer differing views on this phenomenon: some call for stricter regulation of business practices and/or local government interference, while others warn that corporate overregulation could hinder autonomy. While current policies focus on administrative and regulatory improvements, some argue that deeper structural issues must also be tackled.

- For the party, “involution” is no longer seen as merely a domestic economic challenge. If left unresolved, it risks weakening China’s economy and, by extension, its global competitiveness in an increasingly uncertain international environment – a cause for concern for the party leadership.

On China’s commercial cultural exports:

- The growing global appeal of Chinese mainstream cultural products, together with Beijing’s recent measures such as 30-day visa-free access for tourists from more countries and the new “K visa” for foreign science and technology professionals, is strengthening China’s international image and helping its cultural and creative industries reach new audiences abroad.

- The success of China’s commercial cultural exports hinges more on market-driven creativity than on state-led promotion. Despite censorship and strict party oversight, some Chinese creatives skillfully navigate regulatory constraints – such as Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cells within businesses, content moderation in gaming and social media, and tightening export controls on technology – while leveraging government support to achieve success both domestically and internationally.

On how news trends reflect China’s external focus:

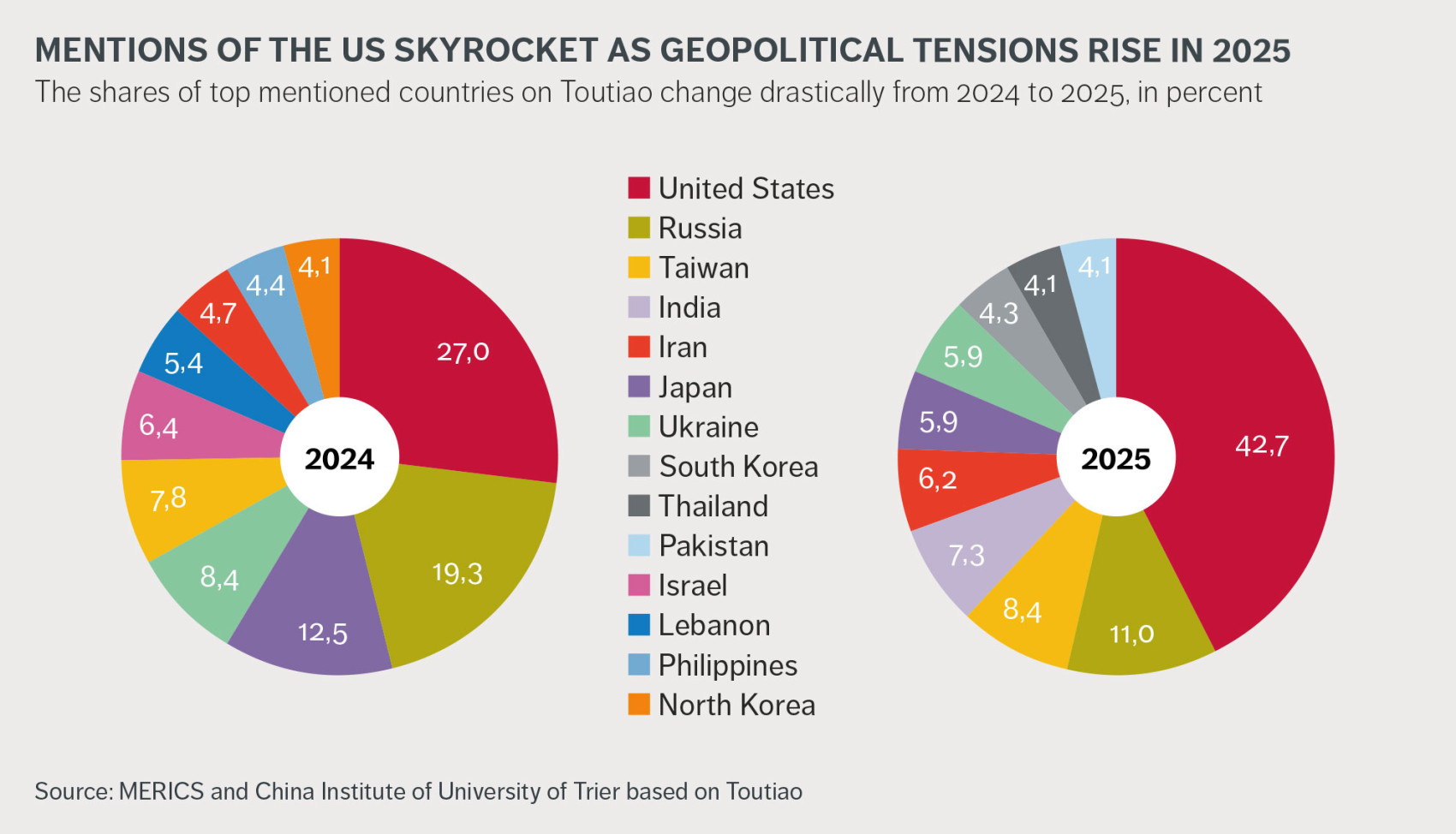

- The popular Chinese news app Toutiao has made the United States (US) a central reference point in its geopolitical coverage, dramatically increasing the proportion of US-related stories to 42.7% in 2025 from 27% in 2024. The platform consistently frames the US within an intentional narrative of a great power in terminal decline, shaping how millions of Chinese users perceive the global hierarchy.

- Toutiao constructs its narrative of American decline through a consistent set of themes designed to undermine US legitimacy. By painting a persuasive picture of American chaos and decay, Toutiao shores up the perception of China as a stable, rational, and competent alternative. This persistent digital messaging frames China not just as a competitor, but as the calm and ready successor on a shifting global stage.

Introduction: The divide between China’s geopolitical and internal affairs is weakening

Geopolitics penetrated domestic online discussions more than ever in 2025, propelled by US-China and South/East China seas frictions and by the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East. Experts and citizens alike have posted views on international tensions and geoeconomic issues, connecting them to domestic problems and experiences.

A China Spektrum analysis of the US-China trade war published in August 20251 found some Chinese citizens calling for patriotic consumption while others were criticizing the party state over the poor economic and labor market situation: “Even though things look like tit-for-tat – you ban chips, we ban rare earths” – the actual damage hits us harder,” wrote one commentator on the Zhihu Q&A platform which is similar to Reddit.

Chinese online commenters have also noted another aspect of the current geopolitical moment, namely the rise in positive perceptions of China relative to the United States. This trend was also highlighted in a Pew Research Survey published in July 20252. The release of DeepSeek’s large-language model (LLM) in January 2025 produced global admiration. Domestic netizens took pride in a Chinese private company’s success in innovative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Some were even surprised by the global praise.

China’s recent technological breakthroughs have boosted its global reputation, but the same system that drives these achievements also relies on heavy censorship at home, a tendency that can constrain open debate and stifle creativity. A leaked censorship directive ahead of Beijing’s military parade marking the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II urged cyber-regulators to stay alert to a long list of “ideological risks.”

Authorities swiftly enforced these guidelines, scrubbing even lighthearted or awkward content. On Weibo, a user who joked, “How come women in the People’s Liberation Army wear makeup, but men don’t?” was suspended for seven days for “spreading hatred.”3

Three areas of domestic debates are highlighted in this 2025 China Spektrum Report illustrating the increasingly interconnected nature between domestic and international issues:

First, economically, the new round of trade frictions with the US has increased the urgency to act on tackling domestic economic problems. China’s deep-rooted overcapacity issue4 has now become not only a problem for international markets but for China’s domestic economy as well. Against this background, economic debates on how to solve economic “involution” – i.e. “cut-throat competition” and unsustainable “price wars” between Chinese companies – have gained momentum. If not addressed effectively, it could weaken China’s economy and, in turn, its global competitiveness – a cause for concern for the party.

Second, culturally, in a moment when global public opinion about the US becomes increasingly negative, Chinese brands have gained international attractiveness. Online debates are focusing on factors for success of global commercial cultural exports and the role of private companies versus state-led initiatives.

Third, our analysis of China’s tightly curated international news headlines shows a shift in tone: while the United States remains the most frequently referenced foreign country – just as last year – it is referenced even more often than in 2024 and now increasingly portrayed as a declining power. This framing serves to legitimize the party’s narrative of China as a more stable alternative system and is used to bolster domestic confidence.

As past Spektrum analyses have shown, the level of nuance, detailed arguments and recognition of policy complexity in these online debates is astonishing. This is all the more remarkable given they occur amid patriotic official propaganda, rigid censorship and an algorithmic logic that emotionalizes, popularizes or polarizes debate.5 At the same time, online and expert debate analysis remains a key tool for assessing the accuracy of party-state narratives in official statements and policy decisions, evaluating their effectiveness, and analyzing the domestic perceptions of geopolitics from within China.

Cut-throat competition is risky in a volatile external environment

Perspectives on solutions to overproduction and the race to the bottom on price

In US President Donald Trump’s second term, US tariff rounds have been targeting all major countries, destabilizing the external environment and threatening China’s export-reliant growth model. This has prompted Beijing to look even more inward and put more focus on addressing the long-standing issues innate to its economic model as it seeks to build a more resilient domestic economy. Since mid-2024, a campaign against “involution-style competition” – or the disruptive impact of overproduction and relentless price cuts – has become a key economic governance issue for the central government as it looks to curb structural overcapacity and the stark imbalance between supply and demand that is causing downward pressure on prices.

Overcapacity is not a new phenomenon in China’s economic development. It has long been a structural feature of the system. The CCP has launched several campaigns in the past to address the issue, achieving short-term results. However, the underlying structural imbalances remained unresolved. Today, overcapacity is also affecting emerging industries. Intensifying competition with the United States and ongoing trade frictions are accelerating the problem and adding urgency to the need for action.

What is “involution”?

Widely adopted in 2020, “involution” was a self-ridiculing term used by China’s youth to voice their grievances around the lack of social mobility and feelings of being forced into excessive work and competition for meager outcomes. But it has become a buzzword among policy makers and economists, ever since the July 2024 CCP Politburo meeting used the word to describe irrational industrial competition.

Economic “involution” describes zero-sum competition for market share, where increased investments produce only stagnant or even shrinking profits. The dynamic plays out in different sectors when a) companies engage in spiraling subsidy-driven price wars and tolerate losses to win customers from competitors, a trend evident, for example, among the e-commerce platform giants and their food delivery services; b) local governments race to subsidize the same key industries trumpeted by the central government, e.g. electric vehicles (EV), solar panels or batteries.7

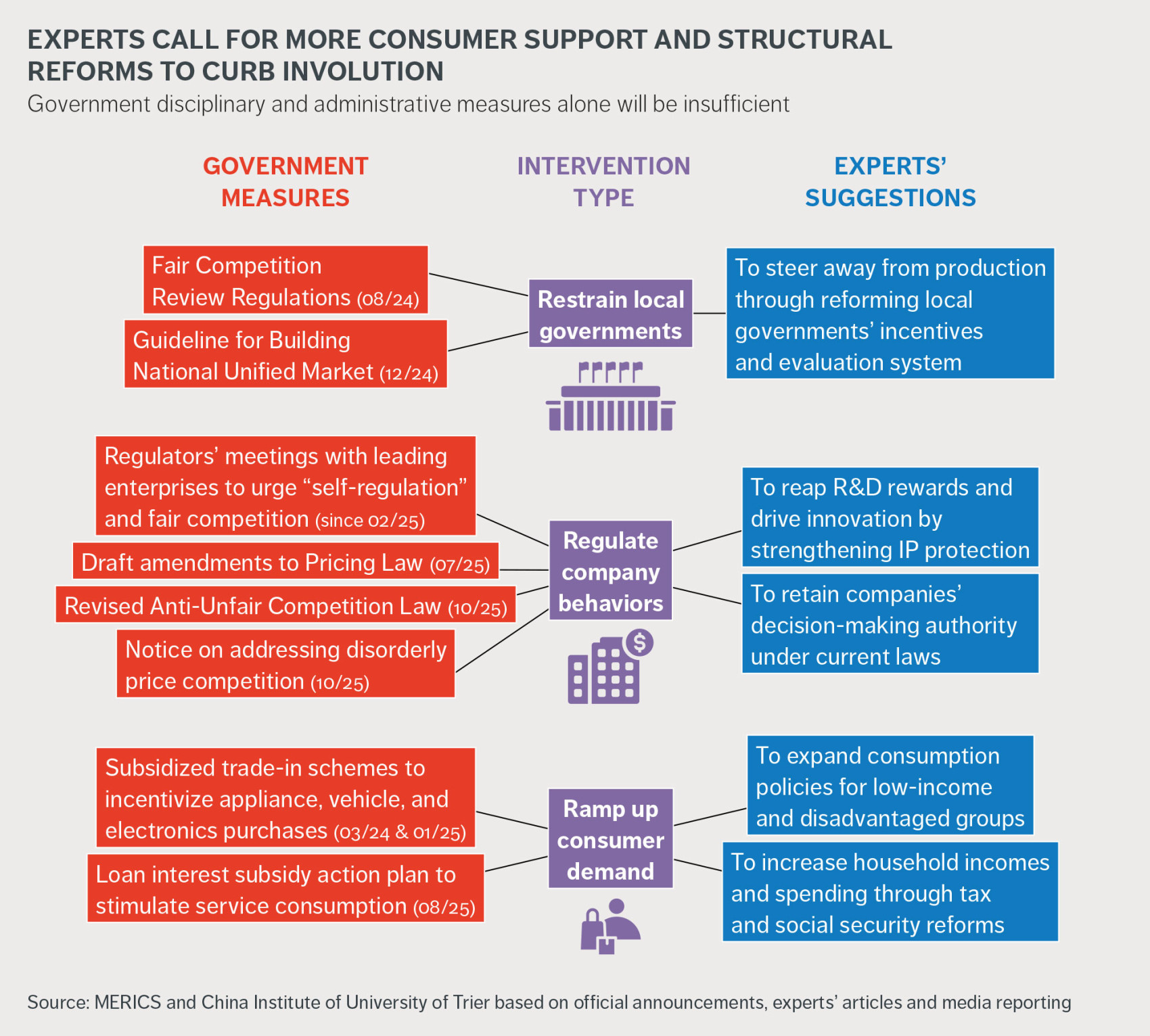

China’s 2025 Government Work Report8 spoke of “tackling ‘involution-style’ competition.” The Chinese state seems to be adopting a multi-pronged approach (see Exhibit 1). Since the launch of the “anti-involution campaign,” experts seem to have more space for debate and are broadly discussing root causes and how to tackle the problem. Many emphasize the need to boost domestic demand, calls that are hardly new. As the argument is well established, this analysis focuses on newer proposals.

“Rein in the enterprises”

Commentary in the party-run Economic Daily9 newspaper represents those calling for tougher party-state action against companies: “Every single case of disorderly low-price competition behavior spotted needs to be investigated and punished, to create a deterrent effect.”10 The opinion piece calls for intensified implementation of newly introduced and revised laws and guidelines on competition, to bring companies back from market-disrupting “involution” onto the correct track of “fair competition.” The article was by-lined “Jin Guanping,” a collective pen name used by the paper’s editorial staff, thereby indicating an institutional stance on the issue, likely reviewed and approved by party officials.11

Liu Yuanchun12, Dean of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, looks to the lessons of the US National Industrial Recovery Act enacted by the Roosevelt administration in the 1930s. It fixed “codes of fair competition” for prices and wages to address deflationary pressures and stimulate economic recovery. Liu advocated for a full-on micro-governance strategy, prioritizing competition policy to foster a shift from the previous self-discipline model to a new model “spearheaded by the government, coordinated by industry and implemented by enterprises.”

Zooming in on the platform economy, researchers from Shanghai Jiaotong University led by Lu Ming13 have proposed specific regulatory measures. They recommend the involvement of law enforcement, with rules to define the acceptable limits of advertising and halt “unreasonable, excessive subsidies or promotional activities.” They called for an intensification of Operation “Clear and Bright” (“清朗” a comprehensive cyberspace campaign to regulate the internet) to rectify platform behaviors such as false advertising and commercial defamation. However, such an approach, reminiscent of Beijing’s anti-trust crackdown on internet giants back in 2020, raises concerns about the possible blow to business confidence.

These perspectives on “involution-style competition” argue that disorderly market behaviors – those that create a race to the bottom on prices – warrant greater government oversight to guide businesses back towards healthier competition.

“Rein in the local governments”

On the other side of the debate, a chorus of voices has urged for a more limited role for the government.

Xue Jun14, an e-commerce law expert from Peking University, believes the fundamental solution to “involution” is continuous market-oriented reform. While Xue supports the regulation of illegal conduct, such as forcing online merchants to participate in subsidizing prices, he is also wary of the abuse of the term. Xue cautioned against labeling all similar practices as “involution.” He argues that enterprises’ operational autonomy on pricing ought to be respected, as long as it doesn’t violate the law. “The real ‘involution’,” he says, “happens in local governments’ conduct”. They should stay within their scope and not meddle in market competition.

Renmin University’s Yang Ruilong15 sees “involution” stemming from local governments interfering in the market-entry and market-clearing mechanisms. “Price competition is a market mechanism driven by enterprises themselves, representing progress compared to the previous approach of government intervention [in tackling overcapacity],” Yang wrote. His proposal urges the recalibration of industrial policies to be innovation-oriented, such as improving property rights incentives.

Huang Shaoqin16, who also prefers to leave competition solely to the market, called for changes to how local governments are incentivized. He sees the root of “involution” not in enterprises but in improper intervention by local authorities. Their policies flooded certain industries (such as photovoltaic and EVs), setting up too many enterprises, squeezing out normal market processes of trial and error and limiting the pressure to innovate. Huang advocates that, in future, local governments’ fiscal revenue sources should be based on property tax to redirect them towards improving the business environment. To stamp out local governments’ “self-assigned authority” in economic decision-making, he advocates a top-down mechanism so “all administrative approval matters need to be reviewed by the central government.” But Huang’s call for such a centralizing measure raises questions over whether it would align with his market-oriented approach to solving “involution”.

Beijing fights “involution” for international gain

The discussion on how to deal with China’s systemic industrial overcapacity (the supply-side of “involution”) is effectively a part of a longstanding debate about the balance of state versus market forces in China’s “socialist market economy,” but has recently acquired a new framing around the issue of “involution”. For the party state it is not only a domestic issue of making its economic growth model more sustainable. In an increasingly uncertain external environment, it needs a more resilient domestic economy to have an edge over its major competitors in global markets.17

To simply “export” its overcapacity to other countries has become more difficult, with looming US tariffs and protectionist measures in other countries as well, fearing their own markets disrupted.

So far, the party has started implementing administrative measures, trying to improve the regulatory framework by revising competition and price laws, for example.

More effective and sector-specific solutions are likely to involve a period of consolidation, disrupting labor markets as some companies and roles vanish while others expand. Once companies exit the market, unemployment will rise, and local government finances will be further strained. How to manage the social impacts of putting a stop to “economic involution” is the topic upon which the debate is likely to continue.

China's cultural competitiveness

China expands its presence in global commercial culture at a time when US soft power ebbs

US President Trump’s return to the White House with his renewed “America First” agenda – marked by transactional, zero-sum trade negotiations – has reoriented US foreign policy toward a more inward-looking, less globally cooperative posture that has been met with pushback. At the same time, China is opening its doors with visa-free travel policies, and the rising cultural appeal of some mainstream commercial products – supported by the production capacity of China’s industrial policy – has created a moment of cultural opportunity. While Washington appears less concerned with sustaining its soft-power image, Beijing has an opportunity to expand its global presence – politically by seeming more outward-looking, and culturally through the visibility and accessibility of its consumer products.

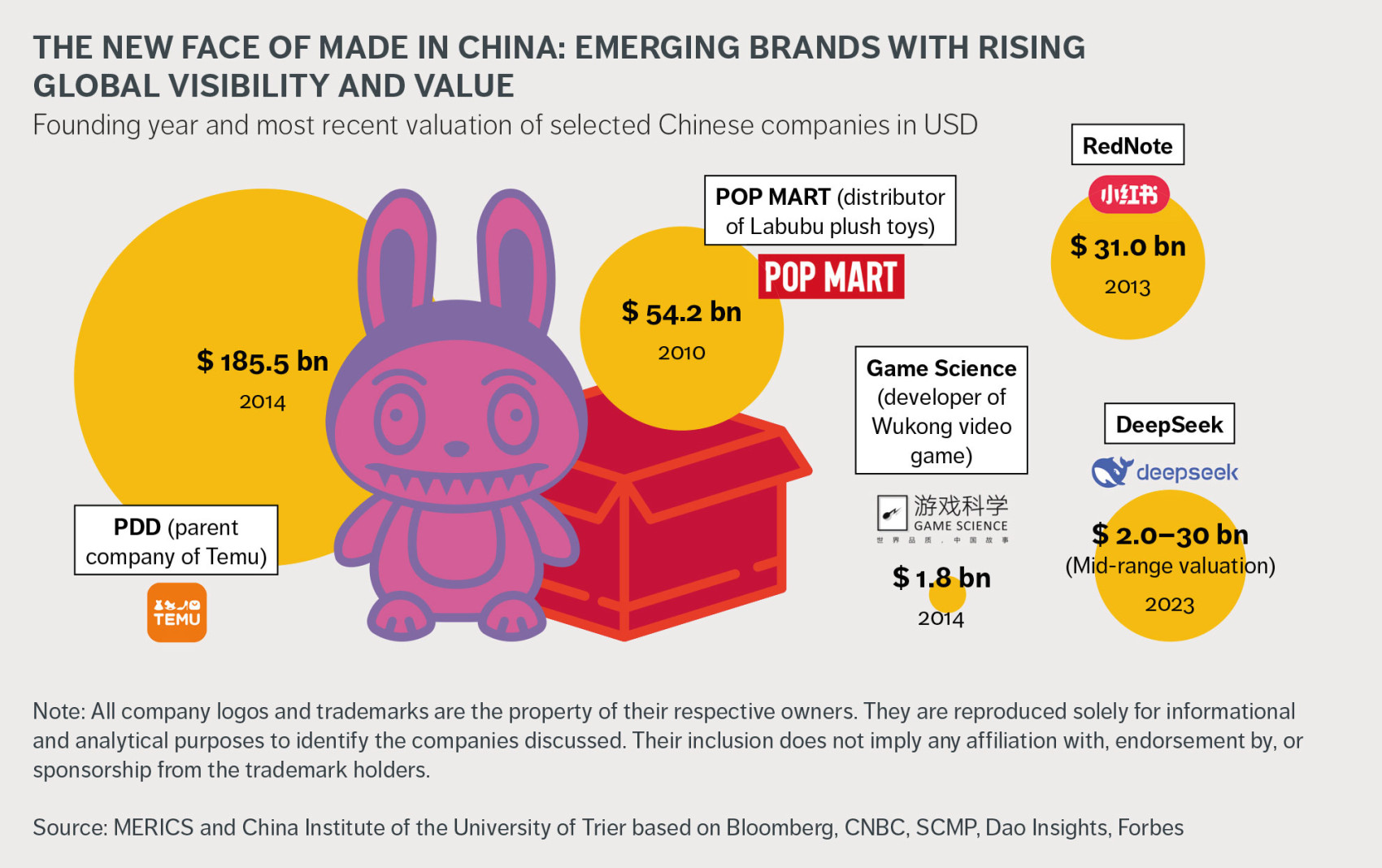

This dynamic is playing out not only in diplomacy and trade, but also in the realm of mainstream, mass culture. Long known as the world’s factory, China is not just exporting products, but also brands, ideas, and cultural touchstones. Pinduoduo’s international platform Temu sells clothing, household items and gadgets that have hooked bargain hunters from São Paulo to Sydney; “TikTok refugees” were delighted to discover Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu (known as Red Note internationally); DeepSeek’s technological leap in AI garnered international respect; and the video game Black Myth: Wukong, with its roots in Chinese mythology and acclaimed for its high production values, has achieved global blockbuster status.18 Even in the fashion industry, the toothy, bug-eyed Labubu toy doll has become an unlikely style icon, dangling from the handbags of celebrities and fashion editors at events in Paris, New York and Milan.

Labubu – A case study in China’s cultural competitiveness

The plush toy character, Labubu, a global cultural phenomenon and Chinese export, has become the driving force behind its parent company Pop Mart’s explosive growth. The "Monsters" line of toys, from which the Labubu character comes, became the brand's top-selling IP with over USD 669 million in revenue in the first half of 2025. Revenue from the Americas grew more than twelvefold compared to the first half of 2024, while sales in Europe and other non-Asia-Pacific regions jumped more than eightfold. The brand has achieved success without state involvement. CEO Wang Ning aims for Labubu to become an everlasting IP, like Hello Kitty or Mickey Mouse. Pop Mart expanded its footprint to 128 overseas stores by June 2025, up from 58 a year earlier, with a focus on the Middle East and Europe. Its overseas momentum is boosted by TikTok livestreaming and celebrity endorsements from stars like Rihanna and Dua Lipa. Labubu’s success shows China’s growing ability to create globally appealing cultural products and highlights the increasing competitiveness of China’s cultural industries in the global market.19

Beijing’s recent decision to grant 30-day visa-free access to tourists from a growing list of countries has produced viral images and videos of foreign influencers exploring tourist sites and engaging with locals.20 In a further attempt to signal openness, China introduced a new “K visa” in October 2025 to attract foreign science and technology professionals – just weeks after US President Donald Trump announced a steep increase in the cost of skilled-worker permits, raising the H-1B visa fee to USD 100,000. While Washington tightens access, Beijing is actively lowering barriers, a contrast that not only bolsters China’s international image but also helps its commercial and creative products find new audiences abroad.

Global public opinion about China is increasingly positive

These trends are unfolding against a backdrop of shifting global opinion. According to the 2025 Democracy Perception Index21, which surveyed more than 110,000 people in 100 countries, a greater number of nations now view China more favorably than the United States – a first in the poll’s history. This shift in sentiment may not only be about geopolitics; it may also reflect the growing appeal of Chinese commercial cultural exports, from social media platforms to consumer trends, which are finding eager audiences abroad.

China’s expanding cultural footprint is filling a space left open by the United States’ partial withdrawal from global leadership under Trump’s more isolationist and confrontational policies.

Debates on why mass cultural exports have gained traction abroad

Online debates on Chinese social media platforms, WeChat and Weibo, contain several perspectives on why China’s cultural exports are gaining traction. On WeChat, one view ascribed success to market competition, insisting that cultural exports should be treated as a business rather than a state mission as profit incentives stimulate creativity better than costly government projects like Confucius Institutes.22 On Weibo, another view was that external recognition follows from strong national development: as China prospers, people – domestic and foreign – will promote it spontaneously, making official campaigns redundant.23

A different Weibo perspective criticized propaganda aimed at foreign recipients overseas as “in essence internal propaganda,” more effective with domestic audiences than abroad, and argued China’s story is best told through cultural products that feel natural and authentic rather than bureaucratic. A similar framing on Weibo sharpened this critique, suggesting that “the day our official external propaganda can also have this kind of ease, instead of always being stiff and self-important, it will truly be unbeatable.” Despite different emphases, these voices agree that China’s cultural influence abroad will not be secured through planned state-led packaging, but through people-driven creativity.24

In the context of these recent commercial successes in mainstream culture around brands and the attention economy, these views signify something has shifted. Despite restrictions such as censorship and strict party oversight, some creatives have learned to navigate the system effectively. They manage challenges like CCP cells in businesses, content moderation in video games and on social media, and tightening export controls on tech products, while also leveraging government support to succeed both domestically and globally.25

When domestic woes harm the Made in China brand

On Chinese social media, Temu’s global rise has sparked a backlash, contrasting sharply with the pride many feel about cultural exports like DeepSeek or Black Myth: Wukong. On Zhihu, one commenter lamented that “the products sold on Temu are all low-quality, low-priced junk, completely ruining the quality that Chinese products have worked so hard to build over the years,” adding accusations of privacy abuses, spam ads, and manipulated reviews that “make the brand feel dishonest from the start.”26

A widely circulated WeChat article framed Temu’s expansion less as a story of Chinese brands “going global” and more as a scramble to find markets after domestic saturation, arguing that “behind Temu’s rapid growth, the future of Chinese brands going global has been quietly stifled.” The author criticized the “involutionary” model that values extreme cost-cutting over innovation: “On Temu, design, research and development, product updates, and brand identity are all irrelevant – only low prices matter.”27

On Xiaohongshu, the critique was more emotional and nationalistic, with users worrying that Temu’s flood of cheap, poor-quality goods “makes Chinese products and people seem tasteless and uninterested in quality,”28 undermining years of progress to improve the global image of “Made in China.” While China seeks to climb the value chain to become known for high-tech, high-quality breakthroughs, Temu’s bargain-basement strategy threatens to undo those efforts.

Commercial achievements abroad do not easily translate into cultural influence

To sum up the Chinese social media debates, commentators agree that success for China’s commercial cultural exports depends more on market-driven creativity than rigid, state-run campaigns. As China’s commercial creative industries gain global reach, some of them have begun to encounter economic and media resistance overseas. The United States has ended its de minimis rule to curb the influx of low-cost Chinese e-commerce goods, and the European Union is considering similar measures.

In international media, the rise of Chinese commercial cultural products is often framed as an expansion of China’s soft power, with such portrayals frequently evolving into narratives of strategic competition, reinforcing perceptions of China as a hard-power challenger29. Consequently, questions remain over how effectively the popularity and attractiveness of these cultural products can offset such reactions – whether justified or not.

The United States as a central reference point in China's geopolitical hierarchy

Geopolitics features strongly in headlines on China’s dominant news feed app

In modern geopolitics, the fault lines are no longer drawn only by diplomats and generals; they penetrate daily life, shaping what Chinese netizens buy and the news they read. This is powerfully illustrated by the massively popular personalized news app Toutiao, with around 410 million monthly active users and 120 million daily users.30 Toutiao plays a huge role in shaping how Chinese people see themselves and the world.

Toutiao’s 2025 news feed consistently presents the United States as a failing empire on the verge of collapse. It is an unambiguous and intentional narrative, crafted using relentlessly negative headlines, a curated story selection, and recurring motifs of American decline.

Recent analysis of Toutiao's headlines31 shows its geopolitical focus has shifted in 2025, with an increase in proportion of US coverage over stories on countries of the Global South. The proportion of US mentions, relative to the other top ten most-covered countries, has grown substantially, from 27 percent in 2024 to 42.7 percent in 2025.

Alongside this heightened focus on the United States, there has been a shift in the level of attention paid to key regional actors. The rankings show a pivot to the Asia-Pacific region, with Taiwan (now #3) and India (now #4) becoming more prominent. Other new entrants like Iran (#5), South Korea (#8), and Pakistan (#10) have replaced previous high-ranked countries such as Israel and Lebanon.

The United States is being positioned as the central reference point within this reframed geopolitical hierarchy.

The United States is presented as a failing power losing control

A review of Toutiao’s top ten headlines from January to August 2025 reveals six dominant narrative frames that combine to make a consistent narrative.

- The US as a failing state: A significant proportion of the coverage is dedicated to cultivating an image of the United States as a country in crisis, a failing state besieged by domestic disorder, natural disasters, and systemic governance failures. Dramatic, absolutist phrasing is used in headlines such as “California fires completely out of control” (美国洛杉矶山火完全失控). This is augmented by portrayals of social collapse, such as “US turmoil labeled ‘rebellion’ by White House” (美国突发内乱 白宫定性‘造反). Collectively, these reports depict a nation teetering on the brink of institutional and social collapse.

- Mockery and delegitimization of leaders: This narrative of systemic failure is personalized through mockery and delegitimization of political figures. The US leadership, particularly presidents Trump and Biden, is frequently represented in terms of ridicule or incompetence. Headlines fixate on personal gaffes, physical exhaustion, or bizarre public behavior that diminish their stature. For example, leaders are depicted as senile or absent through headlines like "Biden was suspected to be asleep at Carter’s funeral and was pushed by his wife" (卡特葬礼拜登疑似睡着还被夫人推搡) or painted as ineffective, with claims such as "California governor said he made five calls to Biden but failed" (加州州长说给拜登打了5个电话没打通).

- Politics as emotional drama and chaos: Political matters are framed as emotional drama, such as in the headline "Treasury Secretary can't stand it and wants to resign" (美国财长受不了要辞职), which suggests chaos and fragility at the highest levels. Even systemic problems are reduced to childish taunts, like "Trump criticizes California Governor: Why is there no water in the fire hydrants?" (特朗普批加州州长:消防栓怎么没水). The news titles serve to undermine not just the leaders themselves, but by extension, the legitimacy and seriousness of US power.

- Waning global influence: Themes of internal weakness are mirrored in the international arena, with coverage emphasizing the erosion of US global influence. The image conveyed is of a superpower losing control, with headlines questioning its authority, as in “Why Zelensky dares to say ‘no’ to the US” (泽连斯基为何敢对美国说‘不), or encircled by the consequences of its own actions, as with “Trump attacked by four major allies over tariffs” (特朗普因关税令被四大盟友围攻).

- Technological hypocrisy and economic self-harm: This portrayal of waning authority is deepened by a dual narrative of technological hypocrisy and economic self-destruction. The United States is depicted as both an aggressor and a victim, engaging in the very behavior it condemns, such as launching cyberattacks on the Asian Winter Games (美国对亚冬会发动网络攻击). Similarly, its trade strategy is portrayed as self-harming, with headlines like “Why unilateral tariffs are a self-entrapment” (为什么美国单边关税是‘作茧自缚), suggesting its economic assertiveness has become a liability devastating its own small businesses.

- China as the rational counterpart: Amid this overwhelmingly negative drumbeat, rare moments of softening do occur. A handful of headlines present the United States in a neutral or cooperative light, often tied to diplomacy, scientific recognition, or cultural exchange, such as “Tu Youyou elected foreign academician of US National Academy of Sciences” (屠呦呦当选美国科学院外籍院士) or reports that “China-US high-level trade talks begin” (中美经贸高层会谈开始举行”). However, these moments are not intended to praise the United States; rather, they serve to position China as a rational and willing partner, prepared to engage constructively even with a deeply problematic global actor.

The narrative spun on Toutiao is more than a simple aggregation of negative news; it is a meticulously constructed worldview. By consistently weaving together threads on US domestic chaos, leadership ridicule, and waning international prestige, the platform presents its millions of users with a cohesive and persuasive portrait of a superpower in terminal decline.

The image shores up domestic confidence in China’s own system as a stable alternative, while simultaneously framing it as the calm, rational successor on a shifting global stage. In the digital arena, great power competition is waged through daily, persistent shaping of perceptions.

Conclusion: Internal contradictions and growing enthusiasm mark China's online debates

The debates around “involution” reveal internal contradictions within China's development model. It is framed either as a symptom of the limits of China’s growth model or as a sign of resilience in the face of economic pressure, particularly amid the US-China trade war. It also highlights how external pressures (e.g., sanctions, tariffs) interact with internal developmental stress. For EU actors, it offers an insight into how China’s domestic economic issues might impact its global competitiveness.

Domestic discourse around Chinese mass cultural products such as Labubu and commercial brands such as Temu shows the growing cultural reach of private enterprises. The debates reveal enthusiasm for China's growing capacity for soft power projection and criticism of limitations imposed by rigid governance. EU decision-makers can use these insights to differentiate between China’s commercial and cultural achievements – realized despite government intervention – and identify instances where Beijing’s repeated interference undermines its own economic objectives, creating openings for Europe to advance.

Internationally, it remains to be seen how Beijing will balance seizing global opportunities – particularly those emerging from the United States's retreat or growing animosity – while managing its relationship with Washington and strategically invoking nationalism when necessary to deflect attention or consolidate domestic support.

Crucially, domestic Chinese debates reveal a spectrum of perspectives, often critiquing how the state tackles key challenges – ranging from managing overproduction and supporting the internationalization of private enterprises to assessing their global appeal and ability to leverage China’s improving image at a time of waning sentiment toward the United States.

Monitoring these debates allows European actors to gain a more nuanced understanding of China's internal discourse, identify credible experts, and better assess the arguments and actors shaping China’s evolving global role.

- Endnotes

1 | Drinhausen, Katja and Sadeler, Christina (2025). “The end of globalization as we know it: How Chinese experts and netizens debate the US-China trade war.” MERICS. https://merics.org/en/comment/end-globalization-we-know-it-how-chinese-experts-and-netizens-debate-us-china-trade-war . Accessed: October 26, 2025.

2 | Pew Research Center (2025). “International views of China turn slightly more positive.” Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2025/07/15/international-views-of-china-turn-slightly-more-positive/. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

3 | China Digital Times (2025). “Censorship Smothers Criticism of Military Parade.” China Digital Times. https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2025/09/censorship-smothers-criticism-of-military-parade/. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

4 | Overcapacity occurs when company production capacity exceeds market demand.

5 | Shen Yang 沈阳 (2025). “新华每日电讯刊文:算法推荐放大‘共振’激化情绪,如何治理 [Xinhua Daily Telegraph: Algorithmic recommendations amplify 'resonance' and intensify sentiment: how to address it].” The Paper 澎湃新闻. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_31576672. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

6 | Xinhua News (2024). “中共中央政治局召开会议 分析研究当前经济形势和经济工作 审议《整治形式主义为基层减负若干规定》 中共中央总书记习近平主持会议 [The Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee held a meeting to analyze and study the current economic situation and economic work and to review the ‘Regulations on Rectifying Formalism to Ease the Burden on Grassroots Levels.’ Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee, presided over the meeting].” Xinhua News. https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202407/content_6965236.htm. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

7 | Hall, Casey (2025). “What is "involution", China's race-to-the-bottom competition trend?”. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/what-is-involution-chinas-race-to-the-bottom-competition-trend-2025-09-14/. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

8 | Xinhua News (2025). “China releases full text of government work report.” Xinhua News. https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202503/12/content_WS67d17f57c6d0868f4e8f0c0d.html. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

9 | Jin Guanping 金观平 (2025). “让市场回归公平竞争的本源 [Let the market return to its origin of fair competition].” Economic Daily. Archived at https://archive.is/LFxe6. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

10 |《关于完善价格治理机制的意见》,《公平竞争审查条例》,反不正当竞争法

11 | China Media Project (2025). “Pen names, stern warnings.” China Media Project. https://chinamediaproject.org/2025/03/25/pen-names-for-stern-warnings/. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

12 | Liu Yuanchun 刘元春 (2025). “破解‘内卷’必须全面启动微观治理,让竞争政策走到C位 [To solve the problem of 'involution', we must fully launch micro-governance and let competition policy take the center stage].” Yicai. Archived at https://archive.is/deUvc. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

13 | Lu Ming 陆铭, Li Pengfei 李鹏飞, Zhong Huiyong 钟辉勇 (2025). “综合整治平台经济‘内卷式’竞争 [Comprehensively addressing the 'involutionary' competition in the platform economy].” 21st Century Business Herald (republished on Aisixiang). Archived at https://archive.is/8OhEb. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

14 | Southern Metropolis (2025). “对话北大薛军:治理平台内卷式竞争,应注重平衡多方主体利益 [Dialogue with Peking University's Xue Jun: Governing platform involutionary competition should focus on balancing the interests of multiple parties].” Southern Metropolis. Archived at https://archive.is/Xiy1A. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

15 | Yang Ruilong 杨瑞龙 (2025). “‘内卷式’竞争并非市场调节过度,而是市场调节不足 [‘Involutionary’ competition is not due to excessive market regulation, but insufficient market regulation].” Beijing Daily. Archived at https://archive.is/UagXb. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

16 | The Economic Observer (2025). “对话黄少卿:‘反内卷’首先要规范地方政府行为 [Dialogue with Huang Shaoqing: To fight against internal circulation, we must first regulate the behavior of local governments].” The Economic Observer. Archived at https://archive.is/WTM4j. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

17 | Xi Jinping 习近平 (2025). “纵深推进全国统一大市场建设 [Deepening the Construction of a Unified National Market].” Qiushi. https://www.qstheory.cn/20250914/e5d3fb14f33c4771ba73977af642e99e/c.html. Accessed: October 16, 2025.

18 | Rina Chandran (2025). “U.S. Tariffs on China Can’t Slow the Impact of Chinese Imports Worldwide.” Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2025/us-tariffs-on-china-imports-explained. Accessed: August 14, 2025; Khadija Alam (2025). “'TikTok Refugees' Drove a Global Xiaohongshu Boom.” Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2025/xiaohongshu-rednote-app-store-downloads. Accessed: August 14, 2025; Gregory C. Allen (2025). “DeepSeek: A Deep Dive.” CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/deepseek-deep-dive. Accessed: August 14, 2025; Tingting Liu and Yuting Yang (2024). “China’s Gaming Industry Comes of Age.” East Asia Forum. https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/11/16/chinas-gaming-industry-comes-of-age. Accessed: October 8, 2025.

19 | Simin Wen and Xintong Wang (2025). ‘Labubu Carries Pop Mart Stock to All-Time High.’ Caixin Global. https://www.caixinglobal.com/2025-08-21/labubu-carries-pop-mart-stock-to-all-time-high-102354054.html. Accessed: August 22 2025.

20 | Kaufman, Arthur (2025). ‘Tour by YouTube Star IShowSpeed Hailed as Soft Power Win for China.’ China Digital Times (CDT). https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2025/04/tour-by-youtube-star-ishowspeed-hailed-as-soft-power-win-for-china/. Accessed: August 14, 2025.

21 | Alliance for Democracies (2025). Democracy Perception Index 2025. https://www.niradata.com/download-report . Accessed: October 26, 2025.

22 | 花猫哥哥 (2024). ‘中国文化输出,为何能走出逆袭之路? [Why Can Chinese Cultural Export Come out of the Road of Counterattack?]’ (Archive.is) Archived at https://archive.is/kN2Tw. Accessed: August 18, 2025.

23 | 埼玉去买菜 (2024). ‘不说人话 [Regarded as a task instead of spontaneous publicity by the people]’ [Weibo]. Archived at https://archive.is/oOKvu. Accessed: August 18, 2025.

24 | 与任何人任何机构都无关的智慧树 (2025). ‘官方对外宣传太僵化 [Official external propaganda too rigid]’ (Archive.is). Archived at https://archive.is/3KMIg. Accessed: August 18, 2025.

25 | China Law Translate (2023). “Measures for the Management of Online Games (Draft for Solicitation of Comments).” China Law Translate. https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/19889-2/. Accessed: October 9, 2025; Nis Grünberg, Katja Drinhausen, and Alexander Davey (2025). “Serving the People by Controlling Them: How the Party Is Reinserting Itself into Daily Life.” MERICS. https://merics.org/en/report/serving-people-controlling-them-how-party-reinserting-itself-daily-life. Accessed: October 8, 2025; State Council (2024). “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Export Control of Dual-Use Items.” DCCXCII. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/202410/content_6981399.htm. Accessed: October 9, 2025.

26 | ‘How to evaluate Pinduoduo cross-border e-commerce temu?’ (2024). Zhihu. Archived at https://archive.is/s1TvV. Accessed: August 22, 2025.

27 | Moss的精神家园 (2024). ‘中国品牌出海被Temu完全打压! [Chinese Brands Are Going Overseas and Are Being Completely Stifled by Temu!]’ (Archive.is). Archived at https://archive.is/LoiPS. Accessed: August 22, 2025.

28 | 德漂小姐姐Mico (2024). ‘我老公在Temu下了两单,我惊呆了 [My Husband Placed Two Orders on Temu and I Was Stunned]’ [小红书 Xiaohongshu]. https://www.xiaohongshu.com/explore/65e0635e0000000004001404. Accessed: August 22, 2025.

29 | Lucenti, Flavia (2025). ‘The “China Threat”: Stereotypical Representations in the US Competition with China.’ International Politics, 62.3, pp. 615–33, doi:10.1057/s41311-024-00555-y. Accessed: 10 September 2025.

30 | ‘Toutiao Advertising in China: Maximizing Your Impact (2025 Update)’ (2025). China Trading Desk. https://www.chinatradingdesk.com/toutiao-marketing . Accessed: August 15, 2025.

31 | We collected the daily top ten headlines from Toutiao‘s hot ranking (头条热榜) between 1 January and 15 August 2025. Each headline was coded by the country mentioned and by tonality. We also did a narrative analysis of the framing of US-linked stories across recurring themes and storylines.

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to thank former MERICS intern Hailey Law for her research support, insights and input during the whole writing process.