Profiling European countries' resilience towards China - 2025 Update

| This analysis is part of the MERICS Europe-China Resilience Audit. For detailed country profiles and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

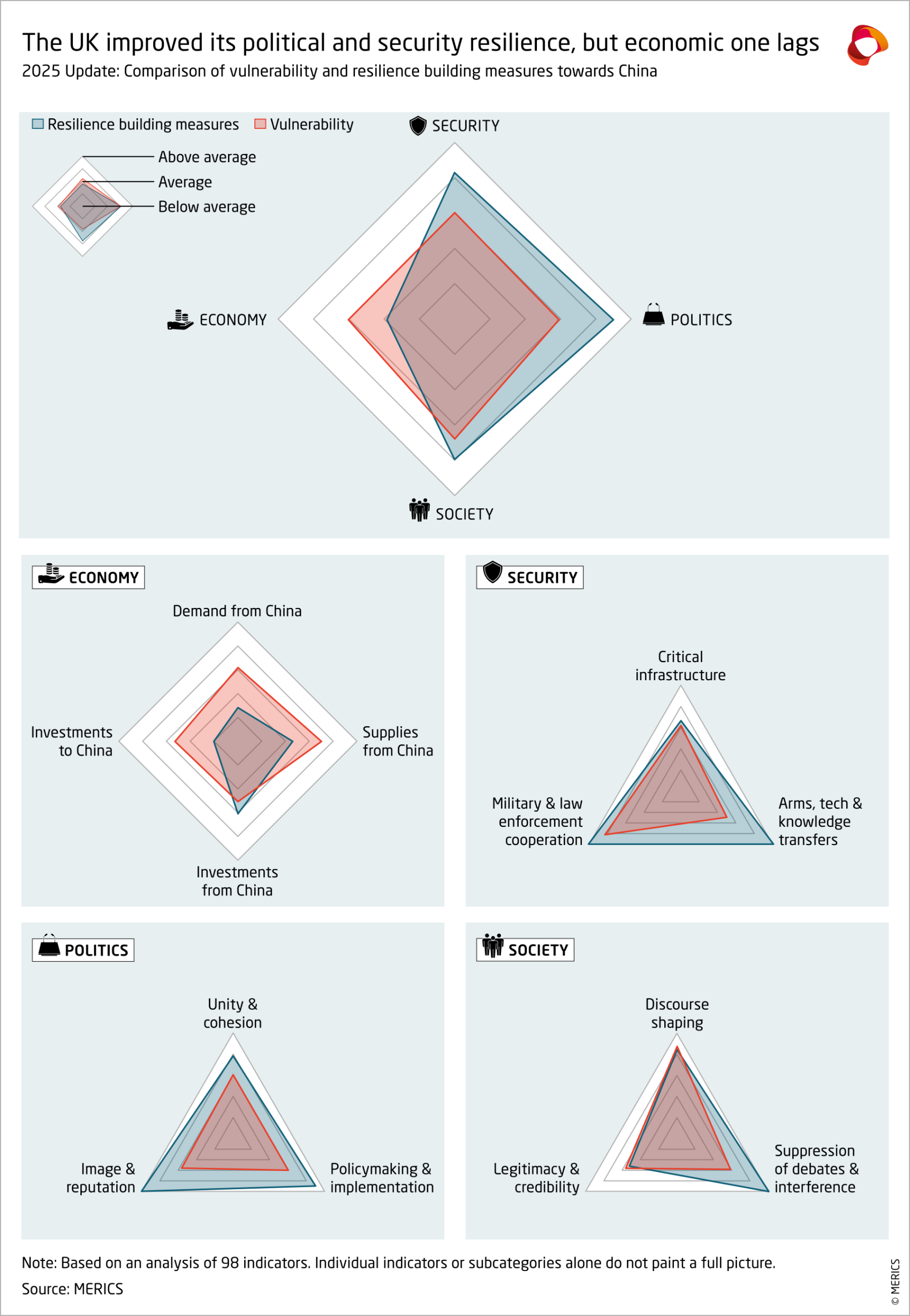

As part of the project “China Horizons – Dealing with a Resurgent China” funded through the Horizon Europe research and innovation program, MERICS has developed an assessment of eleven European countries’ vulnerabilities and resilience towards China. This Europe-China Resilience Audit is built on a database of 98 indicators covering the areas of economy, politics, security and society.

This quantitative exercise is complemented by a series of dedicated qualitative assessments of each country’s specific conditions and level of China resilience. These country profiles summarize the main trends identified in the database, and were reviewed by top China experts from each country. They include updated as well as new analyses, and they cover the following countries (in alphabetical order): Czechia, France, Germany, Italy, Hungary, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

The below profiles of the eleven European countries reflect data and developments from 2025. If you wish to compare the data with our 2024 country profiles, please click here.

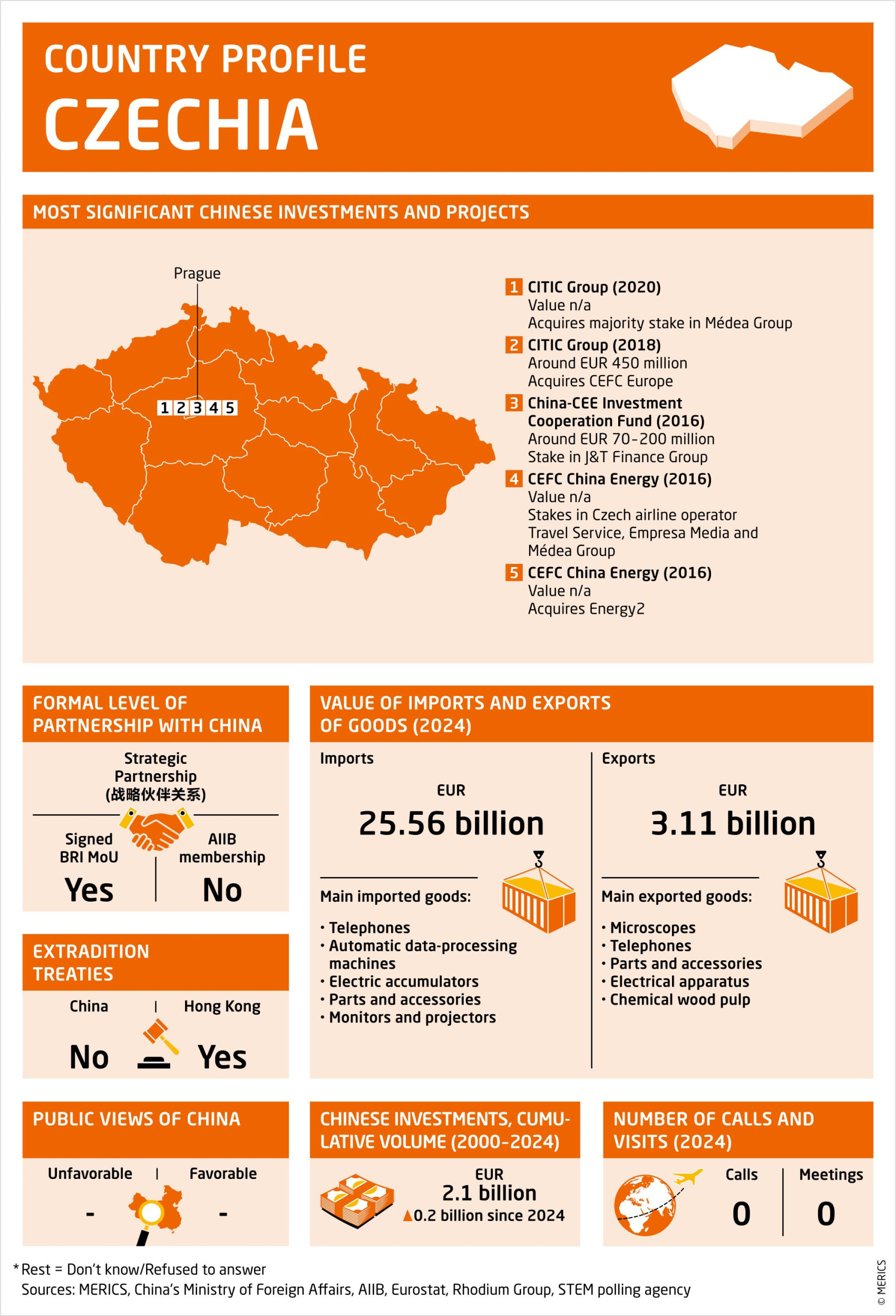

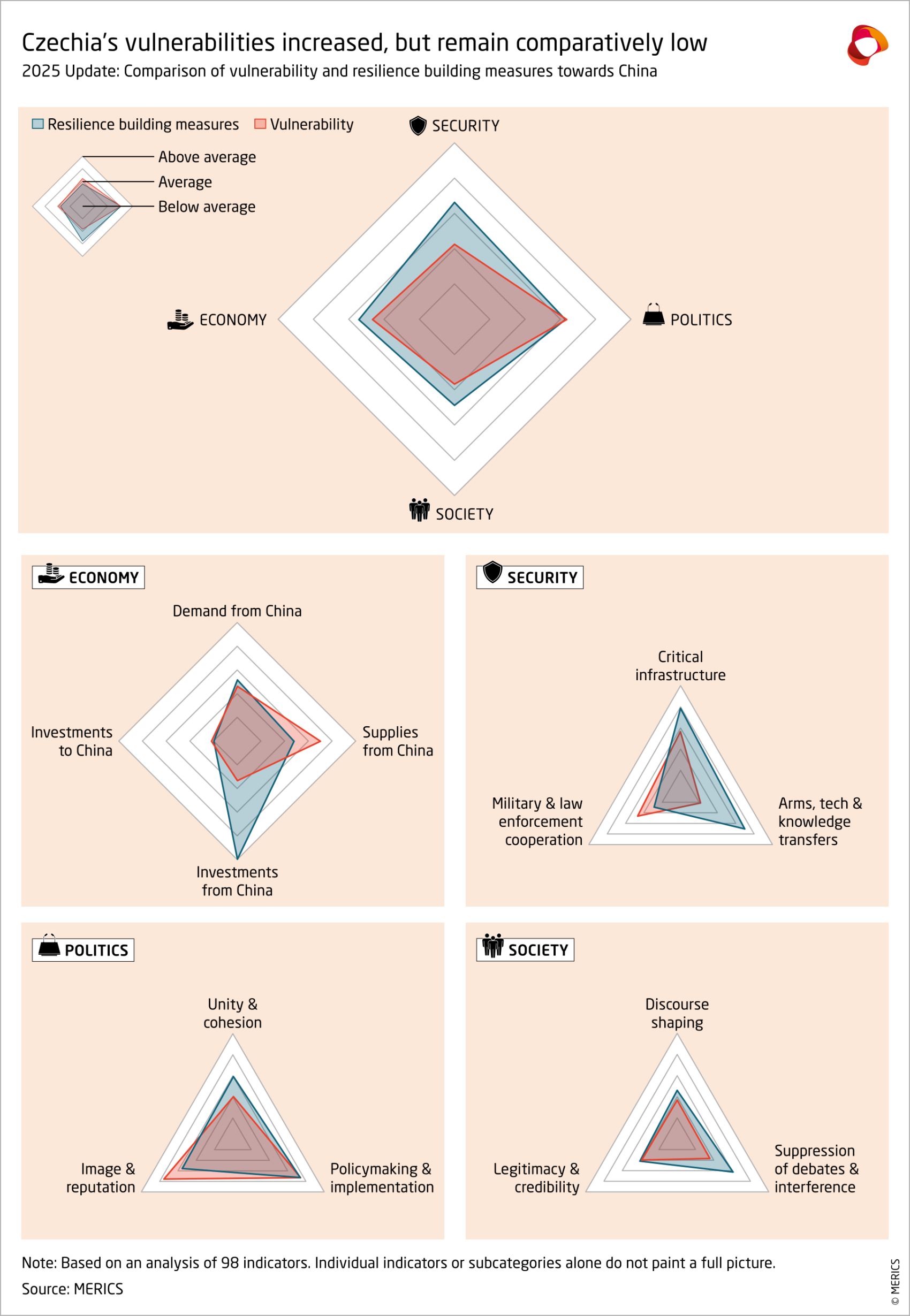

Czech Republic-China relations

The Czech Republic remains one of Europe’s most politically assertive actors in relation to China. Prague has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to test Beijing’s self-proclaimed red lines: It has had several high-level contacts with Taiwanese officials, and President Petr Pavel met with the Dalai Lama in July 2025 – the first such meeting with European head of state or government since 2016. Beijing announced it decided to “cease all engagement” with Pavel, a center-right politician who has no formal link to any party, but the President’s office pointed out that there has been no direct communication with China to begin with. Still, China maintained working relations with the government, creating a fragmented dynamic in bilateral diplomacy.

The Czech Republic has shown an uneven approach to building resilience over the past year. Prague has taken decisive action in some areas, demonstrating its willingness to publicly voice concerns about China. In March, the government of Prime Minister Petr Fiala effectively ordered a dismantling of a Chinese-operated satellite ground-station on security grounds, signaling its willingness to use its investment-screening powers. In May, the government summoned the Chinese ambassador and publicly attributed a cyber-attack against its Foreign Ministry to the APT31 hacker group affiliated with China’s Ministry of State Security. Acting on the advice of its national cybersecurity agency, Prague in July banned the use of the Chinese AI model DeepSeek in public administration.

But gaps in resilience-building remain. For example, the Czech Republic still lacks a dedicated, publicly announced China strategy to coordinate domestic agencies and outlast election cycles, continues to address knowledge security largely reactively and has no legally binding designation of high-risk 5G telecoms providers. The country is politically vocal about China, but it is only partially committed to a domestic resilience-building agenda.

The outcome of October 2025 elections that returned Andrej Babiš to position of Prime Minister may bring about a rapprochement between Czechia and China with the new governments emphasis on pragmatism.

Key challenges for the Czech Republic

- Despite progress on cybersecurity resilience, the Czech Republic has allowed Huawei’s share in national 5G networks to rise from zero in 2022 to 67 percent in 2024, the steepest rise among the countries in our survey. Improvements will hinge on parliament passing the upcoming Cybersecurity Bill, designed to implement EU directives and give the cybersecurity agency new tools to assess the reliability of critical infrastructure suppliers.

- Of the countries we surveyed, the Czech Republic’s economy remains the most dependent on imports from China and Hong Kong, with 13 percent as share of its GDP and 16.5 percent of its total imports linked to China in 2024. This far exceeds the respective averages of 3.9 and 8.1 percent for the other countries in our survey. Although the Czech Republic’s National Security Strategy in 2023 emphasized China’s dominance in strategic supply chains and key commodities, there is no public evidence that Prague has conducted a systematic dependency assessment.

How the Czech Republic stands out

The Czech Republic has one of the most active EU partnerships with Taiwan, with several state bodies involved. Prague places more emphasis on defense and security in its interactions with Taiwan than other European countries. The Czech Republic and Taiwan cooperate closely in supporting Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees through joint projects and memoranda.

The Czech Republic has not been shy to publicly challenge Beijing. Next to it, only the Netherlands has restricted the use of the Chinese AI model DeepSeek in government networks. Prague also stands out for attributing cyberattacks to Chinese groups affiliated to Beijing. Such direct attributions remain rare in Europe – comparable cases in the UK, Finland, and Norway were handled by security agencies and framed more cautiously.

But political momentum in Prague should not be taken for granted. The shift from pro-China engagement under former President Miloš Zeman to Petr Pavel illustrates a tendency across Central and Eastern Europe: With comparatively few direct economic and cultural ties to China, political leaders exert an outsized influence over national China policy compared to their Western European counterparts. This makes the region more prone to abrupt shifts in China policy when heads of state or government change.

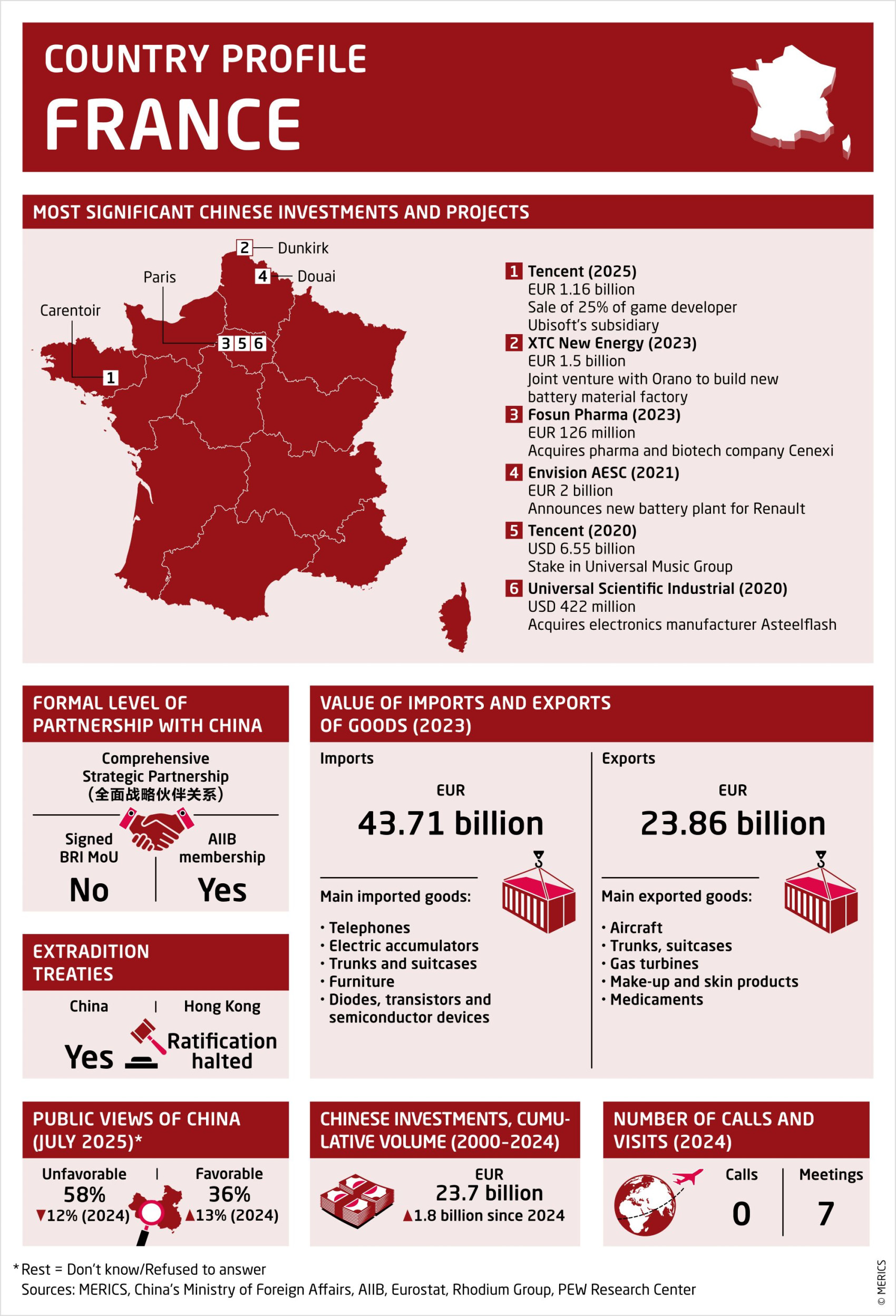

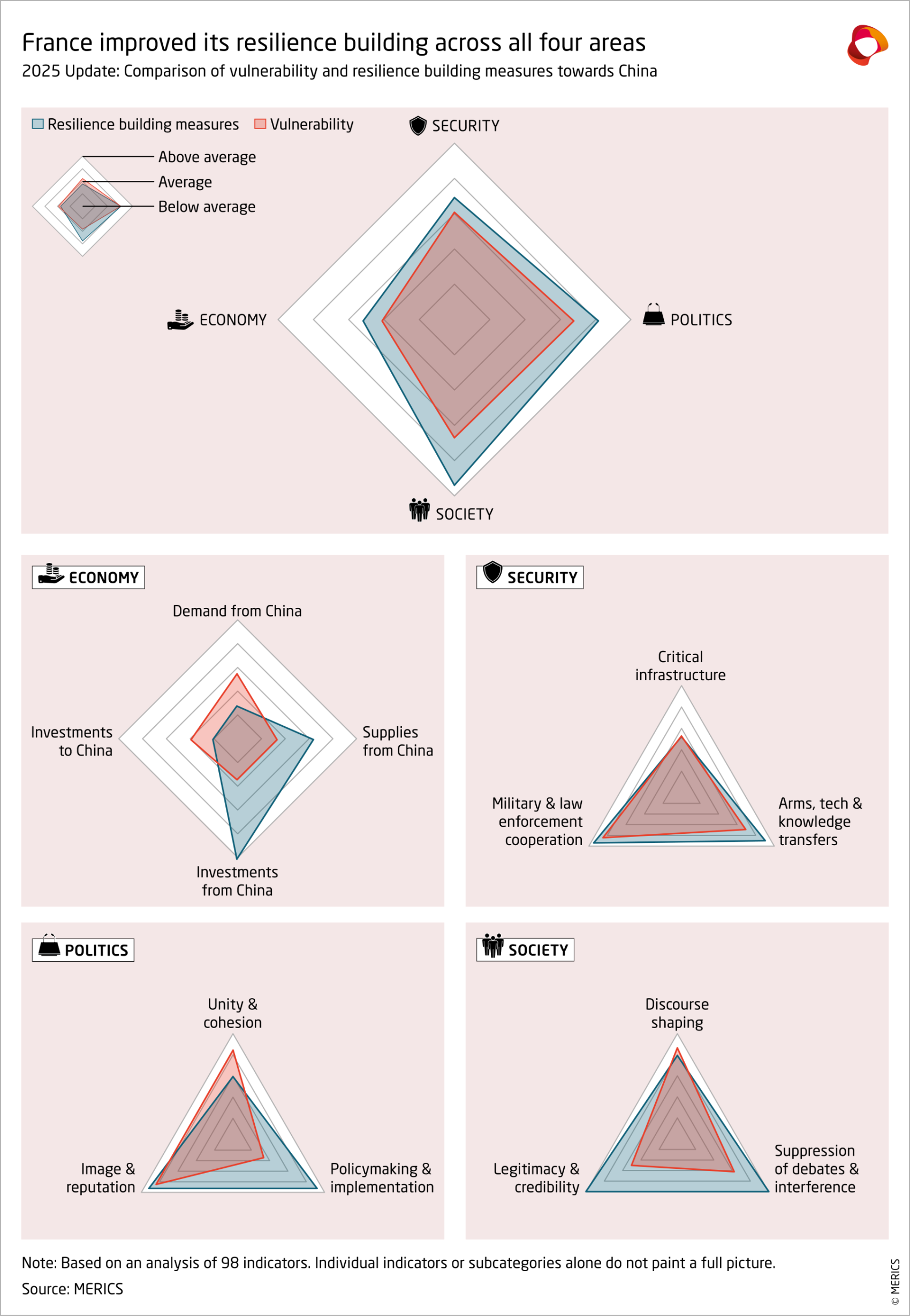

France-China relations

France has been a leading advocate at the EU level for a firmer stance towards China, in line with its ambition for greater EU strategic autonomy and reindustrialization. Paris has consistently supported the European Commission’s trade defense instruments— public procurement restrictions, anti-subsidy tools, the anti-coercion mechanism, anti-dumping investigations, and the renewal of the European Economic Security Strategy.

At the national level, France updated its export control regulations in March 2025, and revised its Indo-Pacific and National Security Strategies in July 2025. But budgetary constraints are limiting its room for maneuver. The government aims to cut overall spending by EUR 40 billion in 2026 – although President Emmanuel Macron has said that defense spending will rise to EUR 64 billion in 2027 from EUR 50.5 billion in 2025.

Political divisions further complicate policy consistency. The current distribution of seats in the National Assembly constrains the government’s ability to adopt significant measures. If the political crisis were to worsen and a new government were to include parties from the fringes of the political spectrum, France’s policy toward China could become less assertive and many of the strategies could come to a halt. For instance, MP Sophia Chikirou of the radical-left La France Insoumise party has, in a report prepared under the authority of the French National Assembly’s European Affairs Committee, called for “a strategic shift in relations between the European Union and China, in favor of cooperation that respects national sovereignty.” She has framed current EU positions as signs of “vassalization” to the United States.

Key challenges for France

- Defense spending aside, budgetary constraints mean that it remains uncertain how the government will finance measures under France’s new National Security Strategy—such as support for reindustrialization or strategic academic investment.

- Following the imposition of higher EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, Beijing has in retaliation targeted selected French exports – for example, Cognac shipments have fallen to their lowest level since the Covid pandemic. With the exception of aerospace, most French exports are non-strategic to China, making it especially vulnerable to such retaliation.

- As part of its reindustrialization push, France welcomed 56 new Chinese projects in 2024, up from 44 in 2023. While some 50 percent involved decision centers and 11 percent R&D facilities, these projects have increased foreign-investment risks like technology transfer.

- Beijing continues surveillance activities in France. The DGSI intelligence agency has identified nine Chinese “police stations,” although their activities were reportedly paused after that. Also, two journalists reported threats from Chinese police after airing their documentary “Is China Policing in France?” on France 2 public television.

How France stands out

France in 2024 and 2025 issued joint statements with China on biodiversity and climate, held a regular defense dialogue, and hosted Chinese participants at its 2024 AI Summit. It stands out for combining such selective engagement with China on global issues with an increasingly assertive stance in areas touching on geopolitics economics.

France’s overseas territories in the Indo-Pacific have led President Macron to claim a voice in the region’s multilateral formats, as highlighted by his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in May 2025). Macron is also pushing for stronger European resilience. A 2024 report by Geoffroy Roux de Bézieux, commissioned by Macron, identified China as “the country that poses the greatest threat to France” in terms of economic security.

France’s leadership at the EU level has drawn Beijing’s attention. After the EU’s investigation into Chinese electric vehicle dumping, China retaliated directly against French exporters. But despite significant pressure, Paris has not sought to soften the Commission’s stance, underscoring its commitment to a firmer European line.

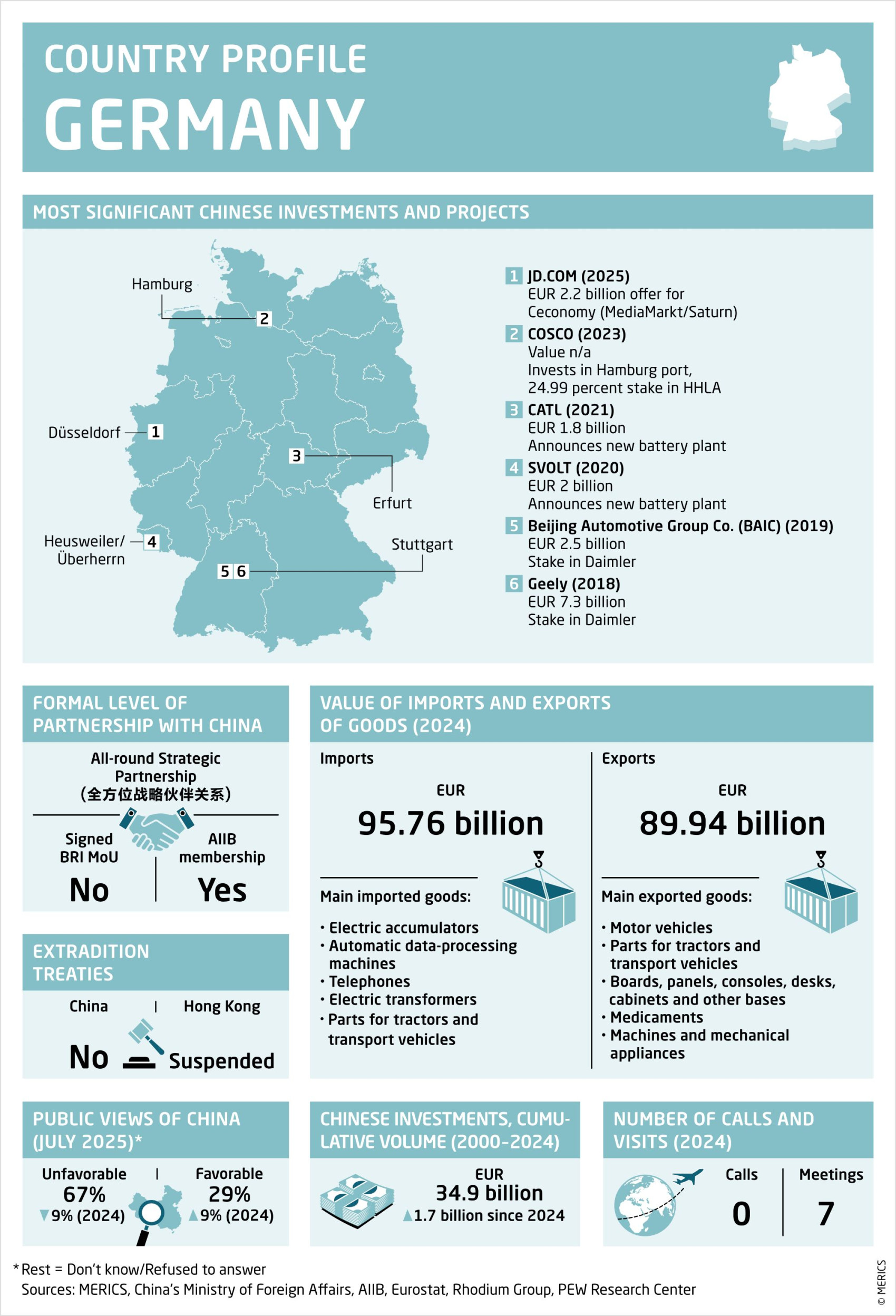

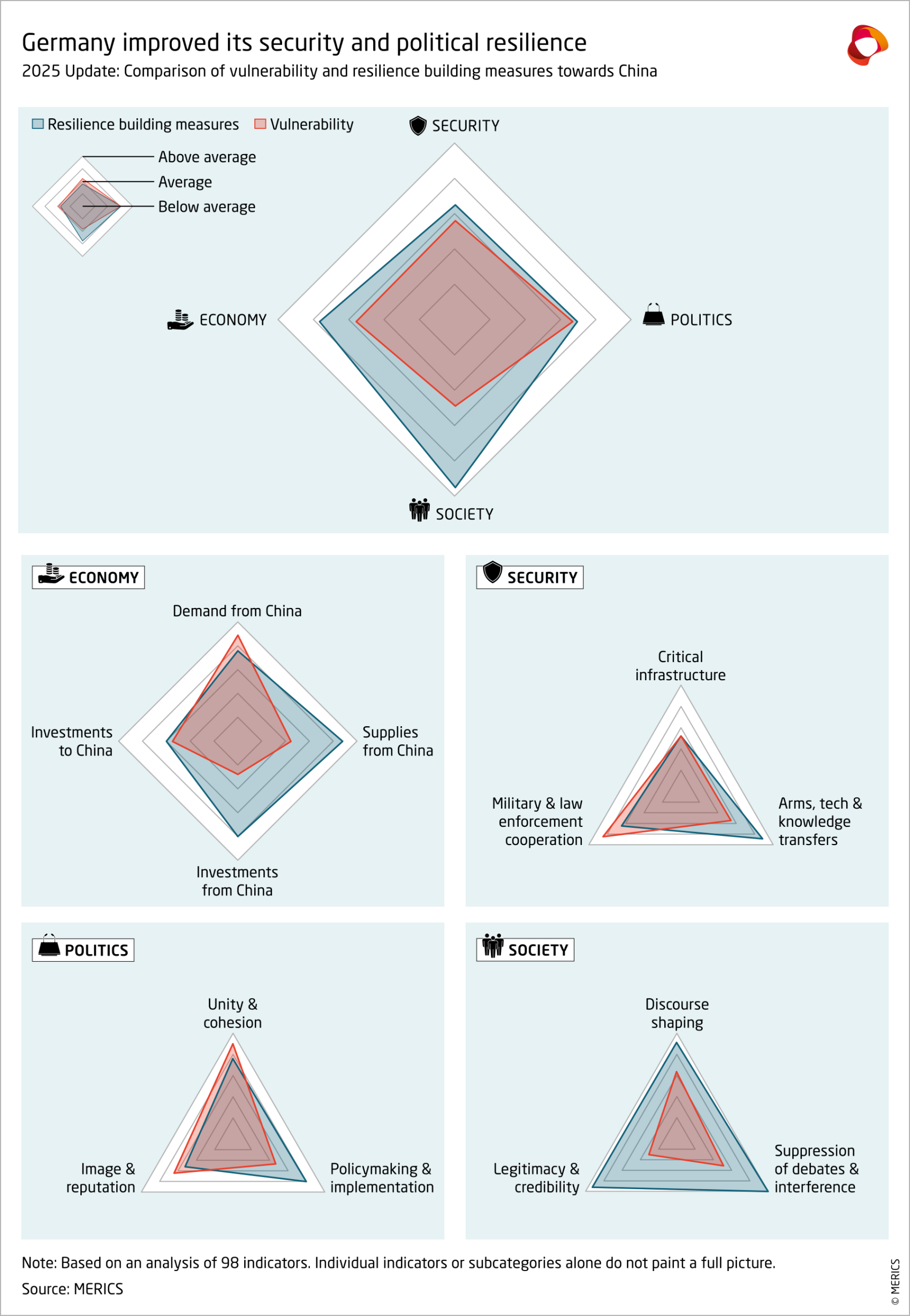

Germany-China relations

Conservative Chancellor Friedrich Merz, in office since May 2025, will have to clarify his position towards China before his planned visit to Beijing later this year. Merz’s CDU-SPD coalition appears likely to pursue a more pragmatic and at the same time risk-conscious approach than the previous SPD-Green government. The coalition agreement pledges that Germany will rework the previous government’s 2023 China strategy in line with "the principle of de-risking”.

Germany’s core industries – notably the automotive or chemical sectors – are under increasing pressure from Beijing’s industrial policy – but are also concerned about ongoing political tensions for fear of retaliation. They are facing direct competition from Chinese firms in the EU and a decline of their exports to China. These trends pose grave risks to Germany’s economy, which was in recession for the second consecutive year in 2024.

But any effort to advance the de-risking of economic relations with China could resonate with public opinion: Two-thirds of Germans surveyed by the Pew Research Center have an unfavorable view of the country. This is the case even after German public perceptions of China improved after the late 2024 US election.

Key challenges for Germany

- Germany’s decline in competitiveness vis-à-vis China is concentrated in the country’s core industries: automotive, machinery, chemicals. Major companies in these sectors have shifted or are in the process of shifting production to China.

- Germany’s exports to the country have dropped by 25 percent since 2019. Companies want to secure access to a market of over one billion consumers in case geopolitical tensions strangle imports – or use China as a “fitness center” to drive innovation. This development is already affecting employment in Germany.

- Germany ranks among the countries that are most dependent on shipments from China. Some 33.4 percent of Chinese imports are concentrated in sectors where alternative sourcing is limited – for example, machinery, textiles, and certain food products.

- Germany’s populist right-wing politicians are receptive to Chinese narratives. The far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has gained in popularity: It secured 20,8 percent of the vote in the 2025 election, doubling its 2021 result. Its co-leader Alice Weidel has significant expertise on China, and the party’s program calls for seizing “any opportunity offered by the New Silk Roads”, while acknowledging China “aims to strengthen China's influence in the world”. Not surprisingly, Beijing appears interested in the AfD: An aide (German citizen of Chinese origin) to MEP Maximilian Krah was sentenced to almost five years in prison for espionage in September 25.

How Germany stands out

Although Germany’s share of exports to China have decreased, its industries still rely heavily on China. German foreign direct investment accounted for 57 percent of total EU investments in China in the first half of 2024, some 2.3 percent of German GDP. Germany remains not only one of the biggest foreign investors in China, but one of the few countries whose investment is still growing. The automotive sector is still betting on China, which could be risky: Companies that are the backbone of Germany’s economy are doubling down on a car market shifting rapidly to the disadvantage of foreign players.

Those same companies have raised alarms over Beijing’s recent decisions to increase restrictions on rare earth exports. Since China accounts for 60 percent of global rare earth production and controls nearly 90 percent of global refining capacity, German companies are warning of a serious threat to their business, if ensuing rare-earth shortages persist.

The Merz administration is investing considerable political capital in driving de-risking. But like other German governments, it has, so far, been reluctant to hurt the short-term interests of its core industries at the EU level (the government of Olaf Scholz notoriously opposed anti-dumping duties on imports of illegally subsidized electric vehicles from China).

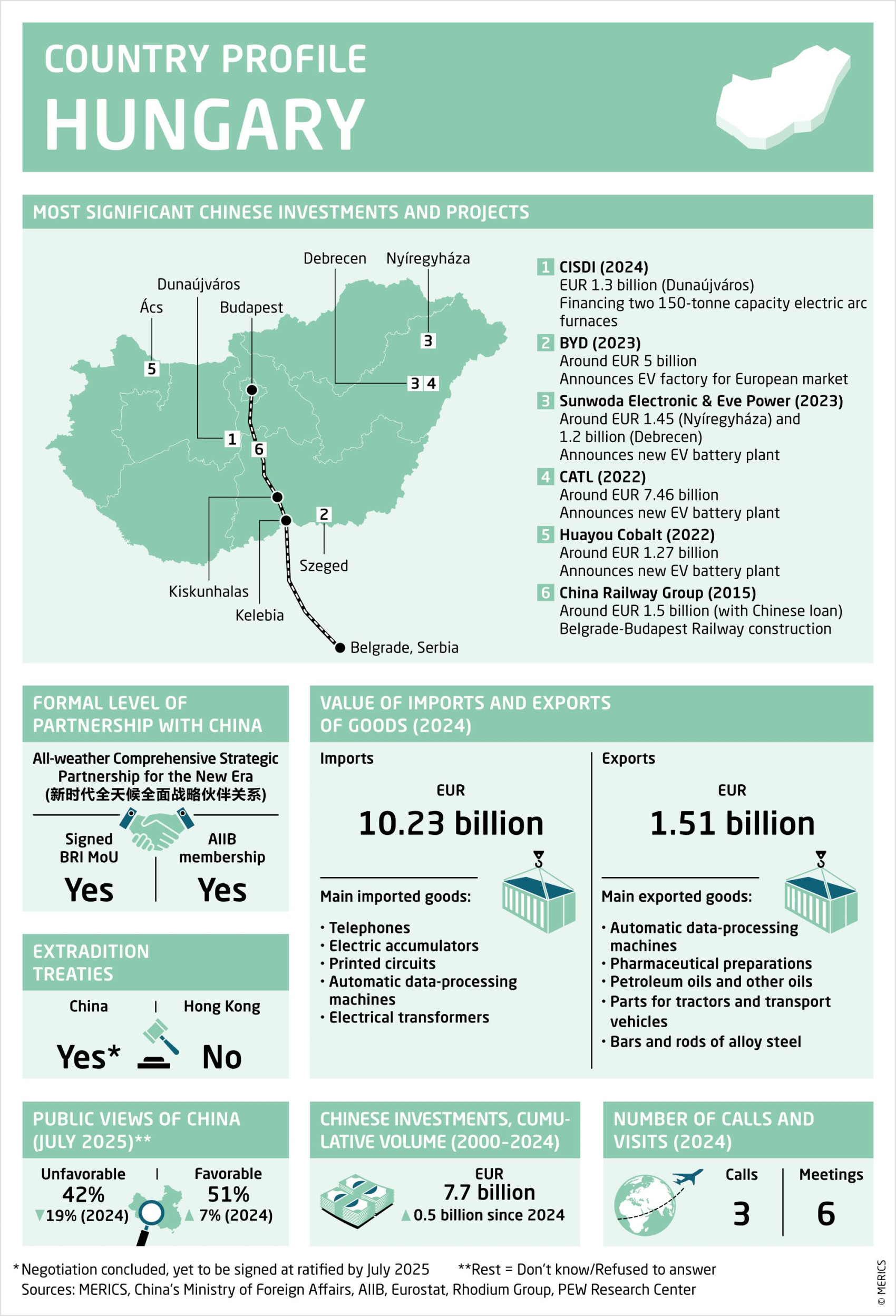

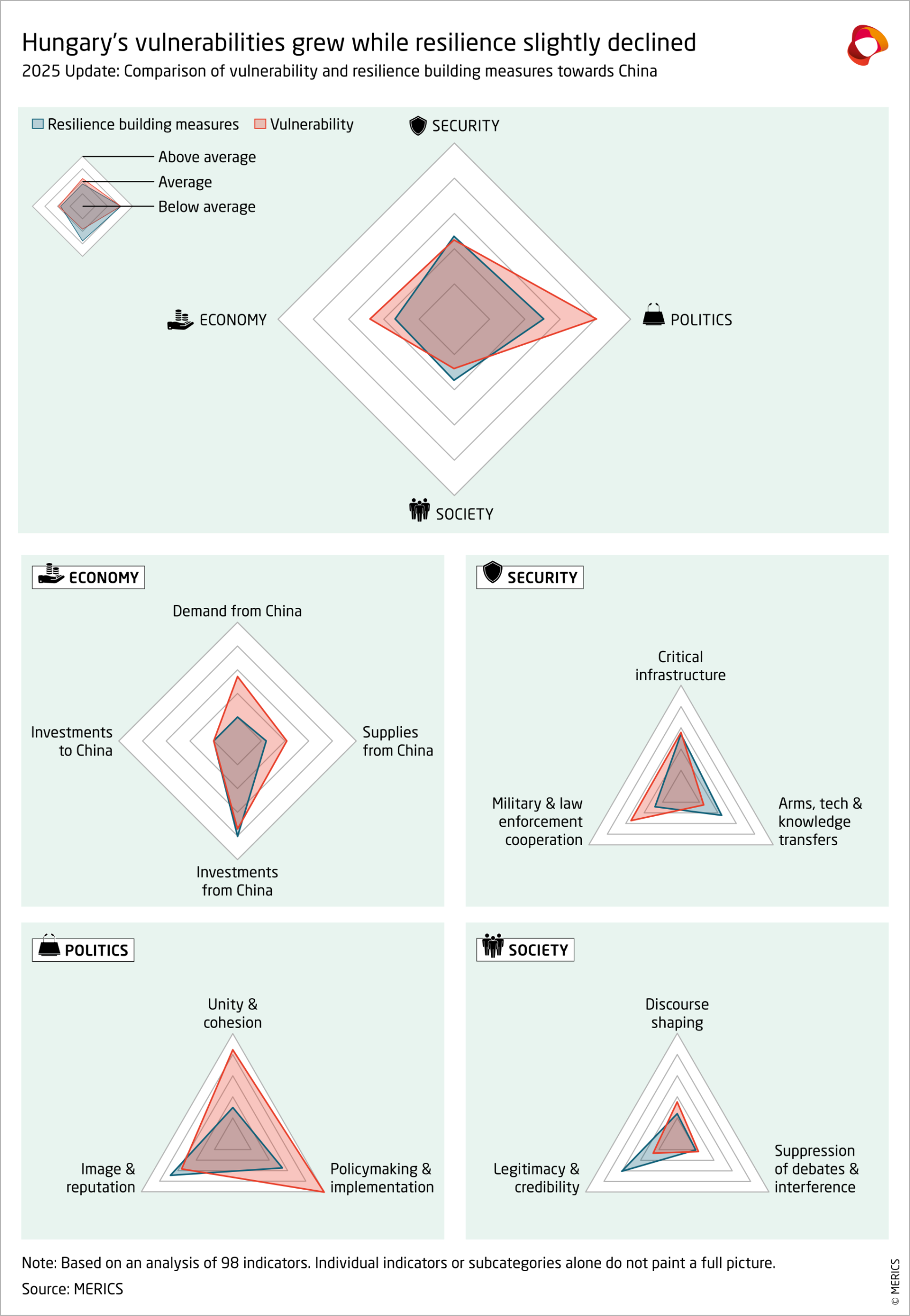

Hungary-China relations

Hungary has strengthened political and economic ties with China through the “All-Weather Comprehensive Strategic Partnership for the New Era”, which the two countries signed in 2024. Although Budapest has not published a specific China strategy, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has consistently positioned himself as the EU’s most vocal supporter of cooperation with Beijing – a position that has paid off economically.

Hungary has deepened economic ties, particularly by attracting Chinese investment in the EV and battery sectors. Hungary in 2024 accounted for 31 percent of FDI inflows into the EU, the highest share in the region. In May 2025, Chinese EV-carmaker BYD announced plans to make Hungary its European hub, with the goal of producing e-buses in addition to passenger cars. But mass production has since been delayed until 2026 – and the European Commission has opened a probe into BYD’s investments to assess potential distortions of the EU’s single market through subsidies from the Chinese state.

Budapest has taken steps to increase resilience, notably by adopting the Act on the Resilience of Critical Entities in 2024, which implements EU requirements to boost critical-infrastructure defenses. But it is unlikely that Orbán’s administration would use these tools towards China’s activity. Indeed, the administration continues to prioritize closer ties with Beijing and has been one of the most outspoken critics of EU de-risking. In 2024, for example, it very vocally opposed the introduction of EU tariffs on EVs made in China.

Key challenges for Hungary

- Hungary remains most exposed to incoming Chinese capital of all the surveyed states. Chinese FDI in the country amounted to at least 2.36 percent of Hungarian GDP in 2023, compared to 0.41 percent average among the other 10 mapped countries. This figure is likely to significantly increase as large Chinese EV and battery projects move from the drawing board to realization. But how many this will be remains to be seen, as some domestic experts are questioning the viability of the projects.

- Following the signing of a law-enforcement cooperation and joint-patrols agreement with China in February 2024, Budapest is reportedly negotiating an extradition agreement. This increases the risk of Beijing using Hungary to intensify its cross-border repression of dissenting members of the Chinese diaspora across the whole Schengen area.

- Hungary’s critical infrastructure remains open to Chinese suppliers. Huawei’s equipment in 2024 made up 62 percent of Hungarian national 5G telecom networks. Despite the new legislative framework on critical infrastructure, Budapest continues to pursue major projects with Chinese participation across a number of sectors, including nuclear energy.

How Hungary stands out

Hungary has several measures in place to strengthen national resilience, including low-threshold FDI screening, due diligence requirements, and a ban on foreign funding of political parties. But while the government’s priority remains the expansion of ties with Beijing, their impact on China will be limited. The example of Hungary shows how resilience-building measures are fail to have an impact if there is no political will to put them to use.

This poses challenges beyond Hungary. Its stance not only blunts EU de-risking and trade-defense instruments but also raises the risk of China circumventing them altogether.

With BYD expected to scale up production in Hungary from 2026, European carmakers will face a new competitive challenge. While attracting Chinese investment is a legitimate goal pursued by several EU member states, there is a risk that Chines manufacturers will exploit Hungary’s direct grants, tax breaks and infrastructure support for competitive advantage and use the plants as final assembly only, allowing vehicles to bypass EU tariffs without meaningful technology transfer. Given the tense relationship between Brussels and Budapest, monitoring and preventing such practices could prove very challenging.

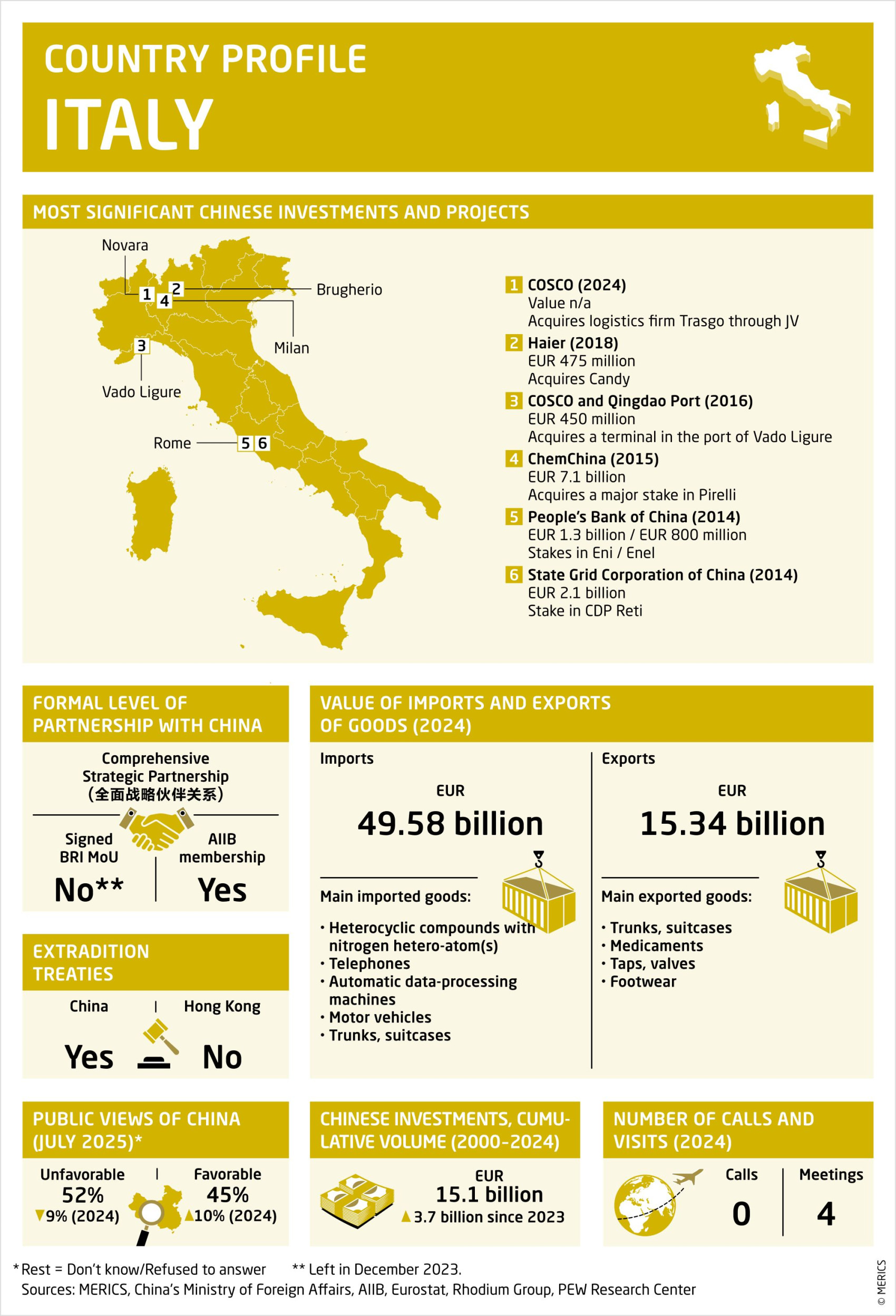

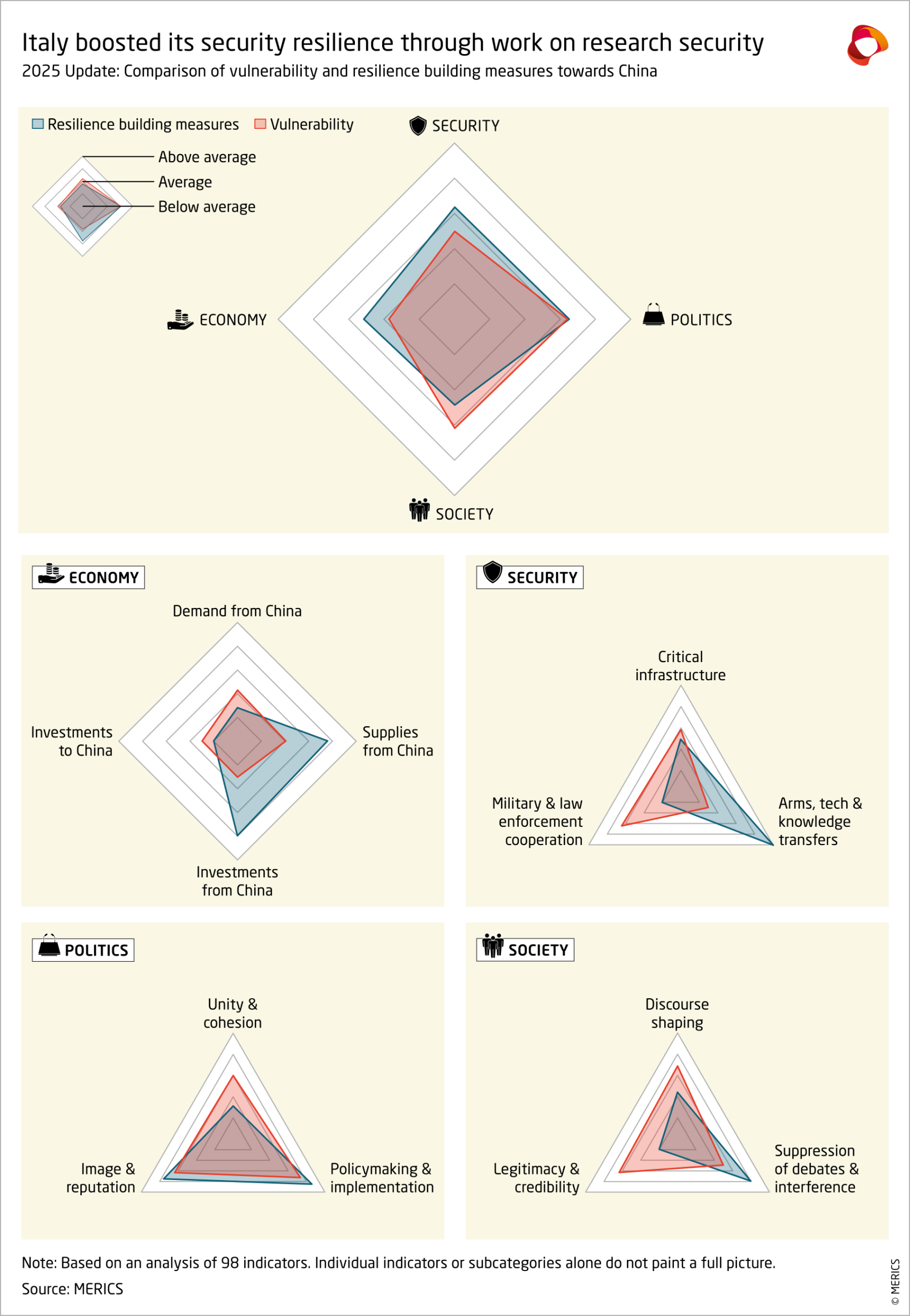

Italy-China relations

Italy is beset by conflicting interests and has yet to articulate a clear China strategy. On the one hand, Rome became the first country to exit the Belt and Road Initiative in December 2023. It also supported EU tariffs on Chinese EVs and has repeatedly used its legal authority, known as “golden powers,” to curb sensitive takeovers by Chinese actors. Lastly, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni cultivates a close relationship with the Trump administration in the United States.

But Rome continues to seek more trade and investment with Beijing. During Meloni’s 2024 visit to China, the two sides signed the Action Plan for Strengthening the Italy-China Global Strategic Partnership. Rome has also encouraged Chinese EV makers such as Chery, Dongfeng, and BYD to invest in Italy or work with Italian suppliers.

Italy’s ambivalence is illustrated by Sinochem’s 37 percent stake in Pirelli: Rome in 2023 restricted the Chinese influence over the tyre manufacturer’s governance. Yet concerns remain, particularly as Pirelli is expanding in the US. Pressure for Sinochem to sell some or all of its stake is mounting, even as Italy continues to court Chinese investments in other areas.

Key challenges for Italy

- While Italy now has an efficient investment screening mechanism, its critical infrastructures remain weakened by past Chinese acquisitions. For example, in 2014 the State Grid Corporation of China purchased 35 percent of the company which operates a third of Italy’s power and gas networks. Italy also still lacks rules on the use of Chinese technology in government IT and on officials’ devices. In addition, it remains the only country in this study without a formal National Security Strategy.

- Although the government withdrew from the BRI with disappointed expectations, regional and local actors continue engaging with China. In Brescia, for example, local authorities are reportedly involved in the Belt and Road Local Cooperation (BRLC) Committee, underscoring the decentralized nature of Italy’s policymaking.

- Legislative oversight remains limited: the Italian parliament raised the fewest motions or questions relating to China, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, or Taiwan among the countries compared (though Czech and Lithuanian parliaments don’t provide comparable trackers of MPs activity).

How Italy stands out

Despite China’s presence in strategic industrial sectors, Italy has taken steps to strengthen national protections. In July 2024, the government expanded dual-use export controls to cover new areas such as semiconductors and quantum technologies. In August 2025, it launched a National Plan to safeguard academia and research, and in June 2025, the Ministry of Defense presented the outlines of a first National Security Strategy – though the announcement attracted limited public or media attention and the process of creating the strategy remains to be completed.

China’s public diplomacy is particularly active in Italy: the Chinese ambassador published more than 20 op-eds and interviews in major outlets, double the activity recorded in any other country MERICS surveyed. Italy also stands out for the strong presence within universities of Confucius Institutes offering China-focused studies. Positive public opinion adds another distinctive element: A July 2025 survey found that 45 percent of Italians viewed China favorably—second only to Hungary among the countries analyzed.

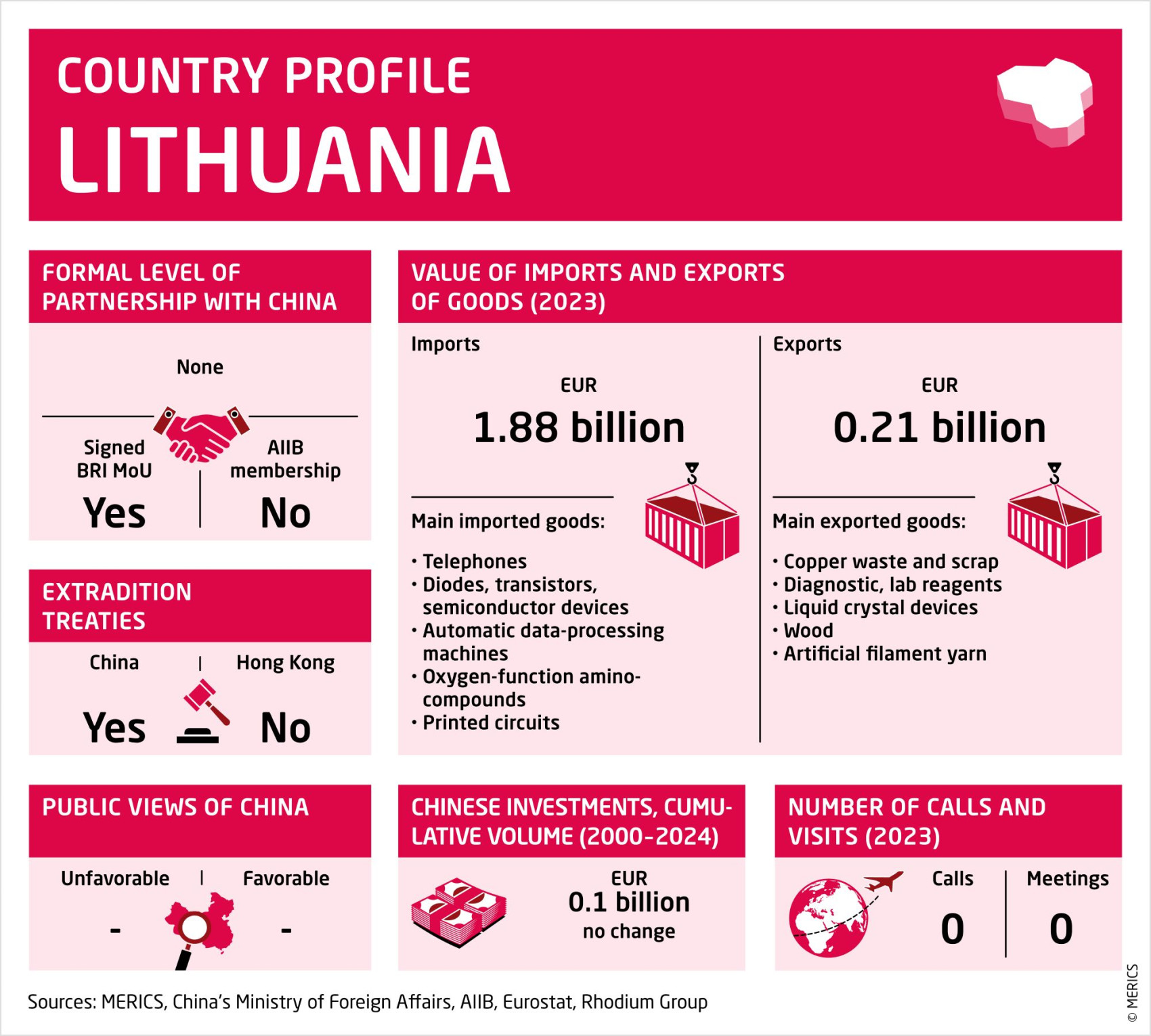

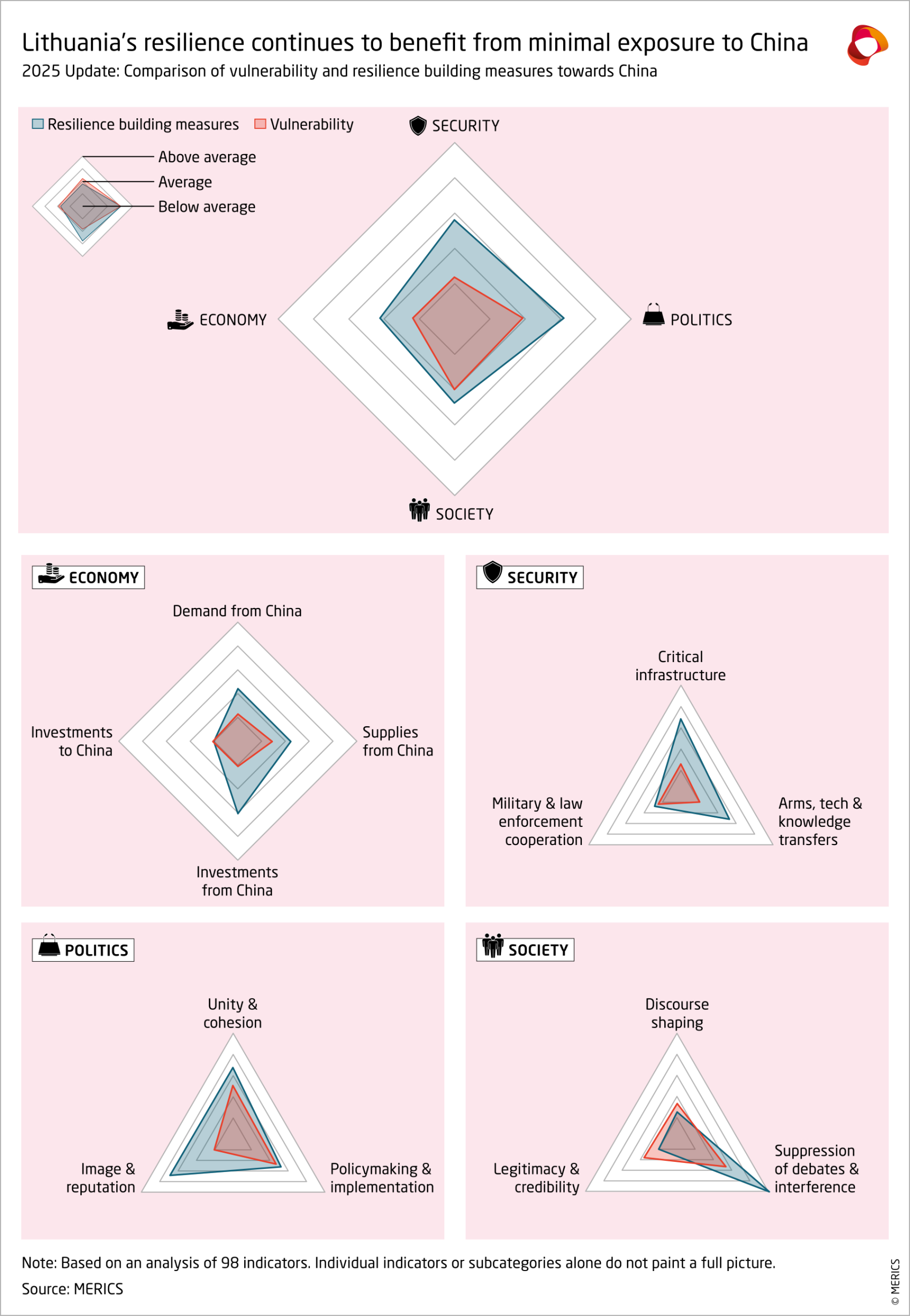

Lithuania-China Relations

Lithuania is one of the countries most resilient to Chinese geopolitical pressure, given severely limited diplomatic and economic exchanges since Beijing retaliated against the opening of a Taiwanese “representative office” in Vilnius in 2021. There are currently no Chinese diplomats and no Chinese companies operating in Lithuania. People-to-people exchanges have also sharply declined since Beijing imposed its de facto embargo.

But Lithuania is struggling to find the direction of its future China policy: Its political parties are divided on the course and costs of normalizing relations. Prime Minister Inga Ruginienė’s Social Democratic Party, which won the 2024 election, has pushed for reestablishing diplomatic relations, proposing to Beijing the accreditation of an envoy in each country. Its Christian Democrat coalition partner has opposed this suggestion.

Vilnius and Beijing remain far apart in exchanges about any normalization of relations. While Vilnius’ has proposed both countries reestablish diplomatic presences, Beijing is adamant that the name of Taiwan’s representative office must change. It will also not have forgotten Lithuania’s expulsion of three Chinese embassy staff in November 2024 and its refusal to allow a last diplomatic representative to re-enter the country in June 2025.

Key challenges for Lithuania

- In view of the possible normalisation of relations with China, Lithuania’s key challenge is to continue building resilience. The country currently has few-China related vulnerabilities, but this could change quickly should relations be resumed.

- Lithuania’s China policy lacks coherence and coordination due to the acute politicization of public debates about China, the small number of China-related institutions, knowledge networks, or experts, and the absence of an official China strategy to set guideposts.

- Several countries including Sweden, Canada and Norway have endured diplomatic crises with China, followed by years of frozen relations. Their experience of eventually normalizing relations with China could help Lithuania develop a resilient pathway.

How Lithuania stands out

While China is not a key topic of public debate in many European countries, Lithuania has the most vibrant political discussions about the country. Both ruling and opposition parties have adopted strong stances towards China, including issues relating to Taiwan.

Lithuania can deal with economic and political coercion from China due to its unique position. In retaliation for European sanctions against Chinese banks supporting Russia’s war efforts, China in August 2025 sanctioned Lithuanian banks UAB Urbo Bankas and AB Mano Bankas, banning them from carrying out transactions with Chinese individuals. These sanctions had no impact on the banks’ operations and did not add to political pressure, given the country’s limited exposure to China.

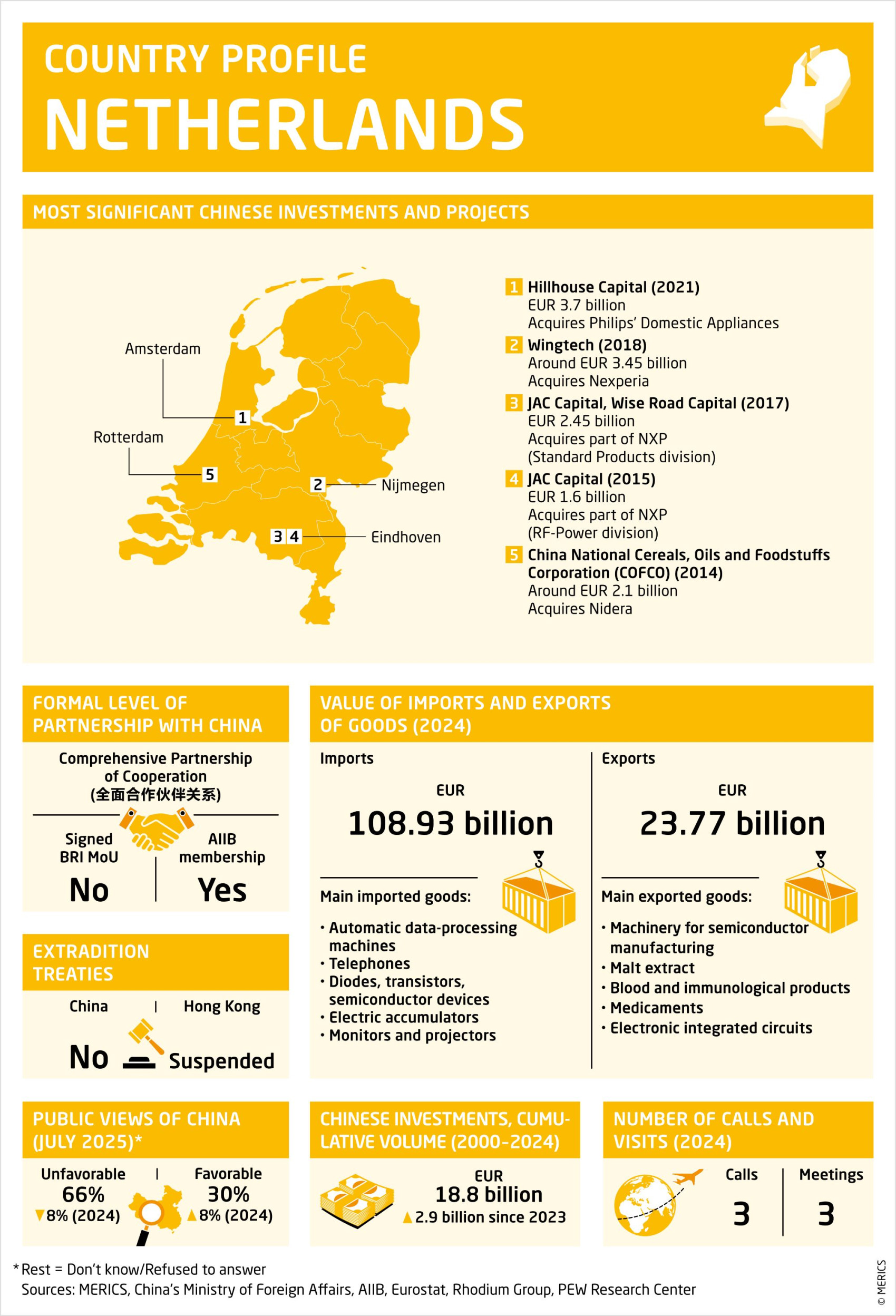

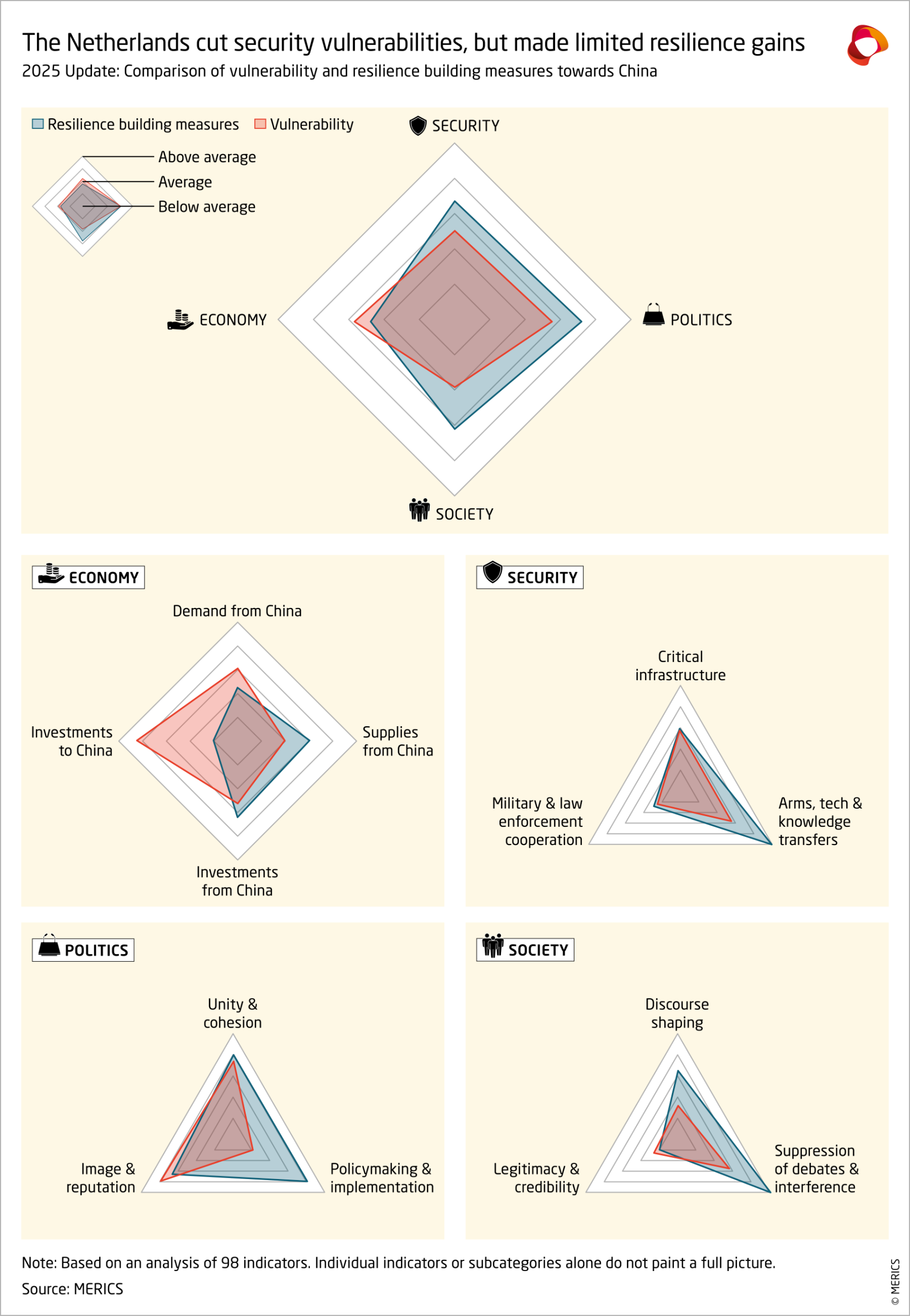

Netherlands-China relations

Dutch awareness of Chinese threats has grown significantly in recent years. Resilience-building has over the past year been marked by an intensified focus on cybersecurity and counterespionage. After discovering malware in 2023, the Ministry of Defense and the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) for the first time publicly attributed a cyberattack on a Dutch defense network to the Chinese state a year later.

The Dutch government also responded with several measures, including a proposal to update the investment screening mechanism (Vifo Act, implemented in 2023) by adding six new critical technologies; the approval of a new law criminalizing digital and diaspora espionage (announced in March 2025); the banning of sensitive apps (such as DeepSeek) from civil servants’ phones; and a reduction in the Dutch market share of Chinese 5G equipment suppliers from 72 percent in 2022 to 37 percent in 2024. Notably, by the end of September, The Hague also took control of chipmaker Nexperia and removed its Chinese CEO over concerns of potential tech transfer to Nexperia's Chinese parent company.

This security-driven approach could be hampered by politics. Prime Minister Dick Schoof’s right-wing coalition collapsed in June 2025, triggering a general election on 29 October 2025. However, given growing parliamentary pressure for a more assertive China policy, it will be difficult for any future government to reverse this trend.

Key challenges for the Netherlands

- The Netherlands was the world’s fourth-largest exporter in 2024 and remains heavily dependent on trade and investment with China. In 2024, trade with China and Hong Kong accounted for 2.4 percent of Dutch GDP, largely driven by semiconductor-manufacturing equipment. Dutch foreign direct investment in China was also the highest among the countries analyzed, representing 4 percent of GDP. While this trade exposure is concentrated on sectors in which China still depends on Dutch technology, Beijing is actively working to reduce its reliance. This leaves the Netherlands vulnerable to potential Chinese retaliation as it pursues a tougher economic de-risking strategy.

- The country is frequently a target of cyber threats, espionage and foreign interference. Intelligence reports highlight that China is “interested in acquiring Dutch high-end knowledge,” whether through cyberespionage, academic cooperation, company acquisitions, or funding students and academics who may access sensitive information. A 2024 report commissioned by the Ministry of Education noted that progress remains patchy, even though universities and research institutes hosting PhD students sponsored by the China Scholarship Council are developing knowledge security policies.

- There is also a need for the Netherlands to strengthen societal resilience. A March 2025 report pointed to Beijing’s interference in Chinese diaspora and attempts to influence Dutch journalists, stressing the urgency of further countermeasures. Moreover, since the government does not publish readouts of bilateral meetings, Chinese statements often shape the international narrative unchallenged.

How the Netherlands stand out

The strategic importance of ASML, the Dutch manufacturer of lithography systems, and of chipmaker Nexperia makes the Netherlands a critical node in the global and European semiconductor supply chains, placing it in the heart of the US-China trade war. Under US pressure, the Dutch government banned ASML from selling its most advanced equipment to China, preventing Beijing from producing cutting-edge chips of the highest order. Export controls have gradually expanded since, even as ASML has warned of negative consequences for the computer-chip industry. The company reported significant financial losses in early 2025. The case of the Dutch government seizing control of Nexperia also presented a clear case of protection against tech transfer, a likely harbinger of increasing geopolitical impact on European companies.

China policy has also become part of the broader public and governmental debate in the Netherlands. The government has commissioned numerous studies to deepen its understanding of China, both in response to parliamentary recommendations and through the MFA-coordinated Dutch China Knowledge Network that connects Dutch think tanks and universities in support of building up the government’s China capabilities.

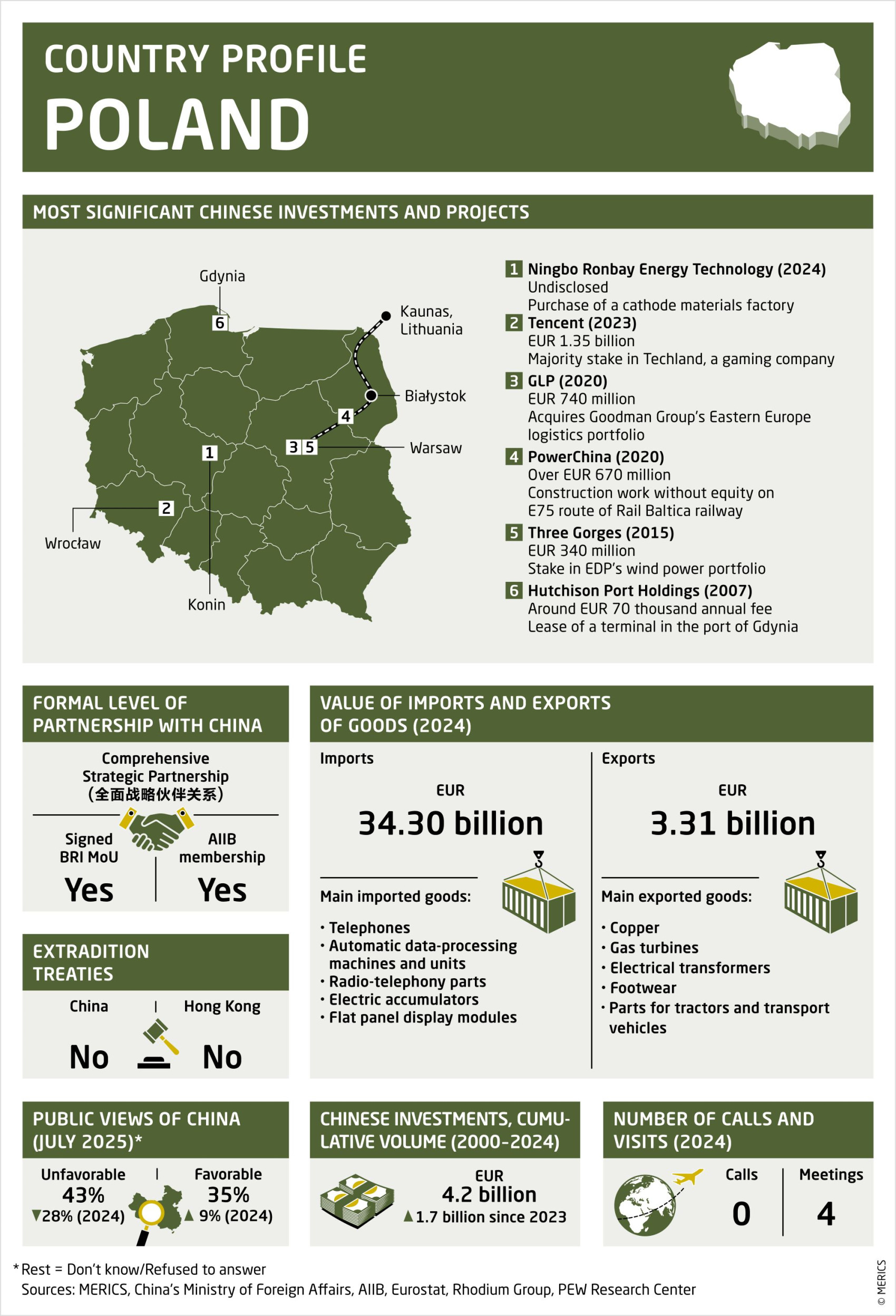

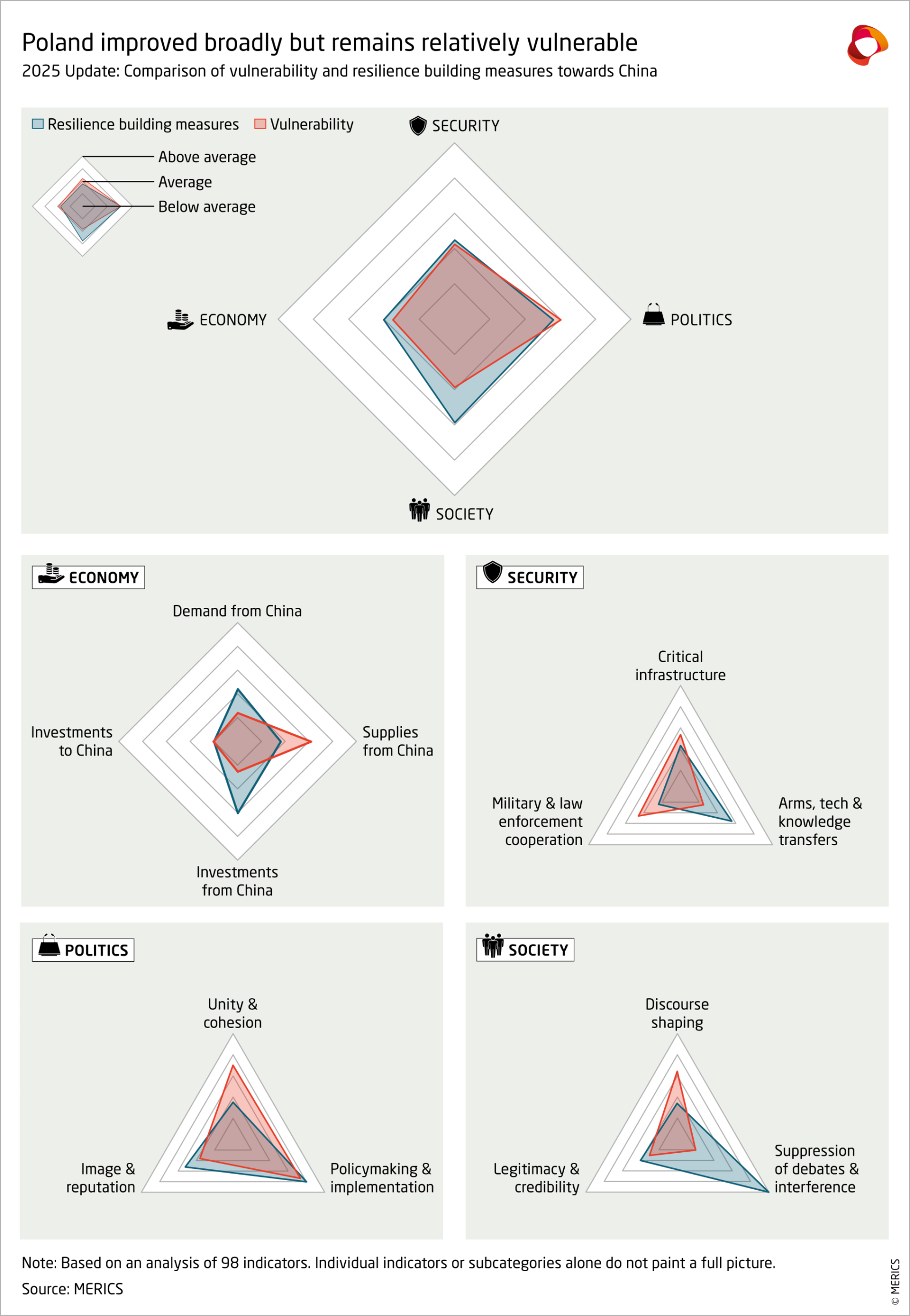

Poland-China relations

Poland maintains a low-profile China policy, balancing economic engagement with concerns over China’s support for Russia and its security dependence on the US. Warsaw’s interest in economic engagement intersects with such geopolitical considerations as shown by two Poland-Belarus border blockades in June 2024 and September 2025 that led to the suspension of the Europe-China rail services. Yet, by signing the bilateral new Action Plan on Strengthening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (2024-2027), Poland and China established joint working groups on trade and investment, whose agendas clearly signal Poland interest in bolstering agrifood exports and attracting green-tech investments (in particular in EVs).

Warsaw’s desire to build resilience against security risks originating from China appears to have receded as the impact of China’s industrial policy on Poland and the rest of the EU has become more pronounced. Prime Minister Donald Tusk supports measures by the EU to boost economic security and trade-defense measures, such as tariffs on Chinese EVs. Tusk and his government are happy to avoid any leadership role regarding China.

The end of Andrzej Duda’s term as president in August 2025 may shift relations towards the prime minister and his government. New president, Karol Nawrocki, has yet to indicate his China stance. Duda, who like Nawrocki is linked to the right-wing Law and Justice Party, led diplomatic engagement with Beijing during his decade in office. He made an extended visit to China in2024, which culminated in the signing the Action Plan.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is expanding its China-focused diplomatic network, creating a working group to monitor China–Russia ties, and upgrading interagency coordination from information-sharing to policy alignment. Those expansions may offer a point of reference to other member states, especially those that have traditionally not invested as many resources into China capacity as Warsaw does.

Key challenges for Poland

- The Ministry of Digital Affairs indicated in March 2025 it has no plans to ban or restrict Huawei equipment, even amid renewed appeals from Brussels. The company’s share in Poland’s 5G networks rose from 38percent in 2022 to 45 percent in 2025, making the country one of only three states covered in our research so see a notable increase – the others being the Czech Republic and Hungary. Yet, the draft amendment to Poland’s Cybersecurity Act presented in October 2025 could, if passed, change Warsaw’s approach to Chinese telecom suppliers.

- Poland’s foreign direct investment screening still omits several EU-recommended critical sectors, like media, and has high thresholds before kicking in. A recent update of the FDI screening shifted oversight from the apolitical Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK) to the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology. This should give the government a key role in coordinating action on blocking sensitive foreign investments.

- The Polish government still lacks official China or Indo-Pacific guidelines or strategies, but these are said to be under consideration for the latter region. Polish politicians’ interest in China remains relatively low, although the number of questions posed by parliamentarians on China more than tripled in 2024 compared to the average of the three preceding years. Then again, this burst of could well have been a result of China visit of President Duda.

How Poland stands out

National security considerations remain an important factor in Poland’s assessment of its interests and vulnerabilities regarding China. Amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, Warsaw relies on NATO, meaning any shift in the alliance’s position on China could also change Warsaw’s stance. Furthermore, Poland leads Europe in defense spending, earmarking 4.7 percent of GDP for outlays in 2025, and more thereafter. This heightens the need for Poland to consider the impact of potential Chinese coercive supply-chain disruptions. For example, rare-earth export restrictions could affect European defense procurements.

In addition, Poland has been lagging in building cybersecurity resilience vis-à-vis China – evident in the delays in introducing regulation on 5G high-risk vendors and the continued lack of published guidelines on the usage of Chinese equipment by Polish authorities.

Poland is one of the EU member states most dependent on imports from China. Almost 12.5 percent of Polish imports come from China or Hong Kong – even if only 1.1 percent of Polish exports go to China, the second lowest score after Lithuania. Indirect economic vulnerability is also a challenge – for example, when German automotive producers suffer, so do their Polish suppliers. Warsaw is looking to lower this risk by attracting Chinese EV investments to diversify into new supply chains. But the process remains challenging.

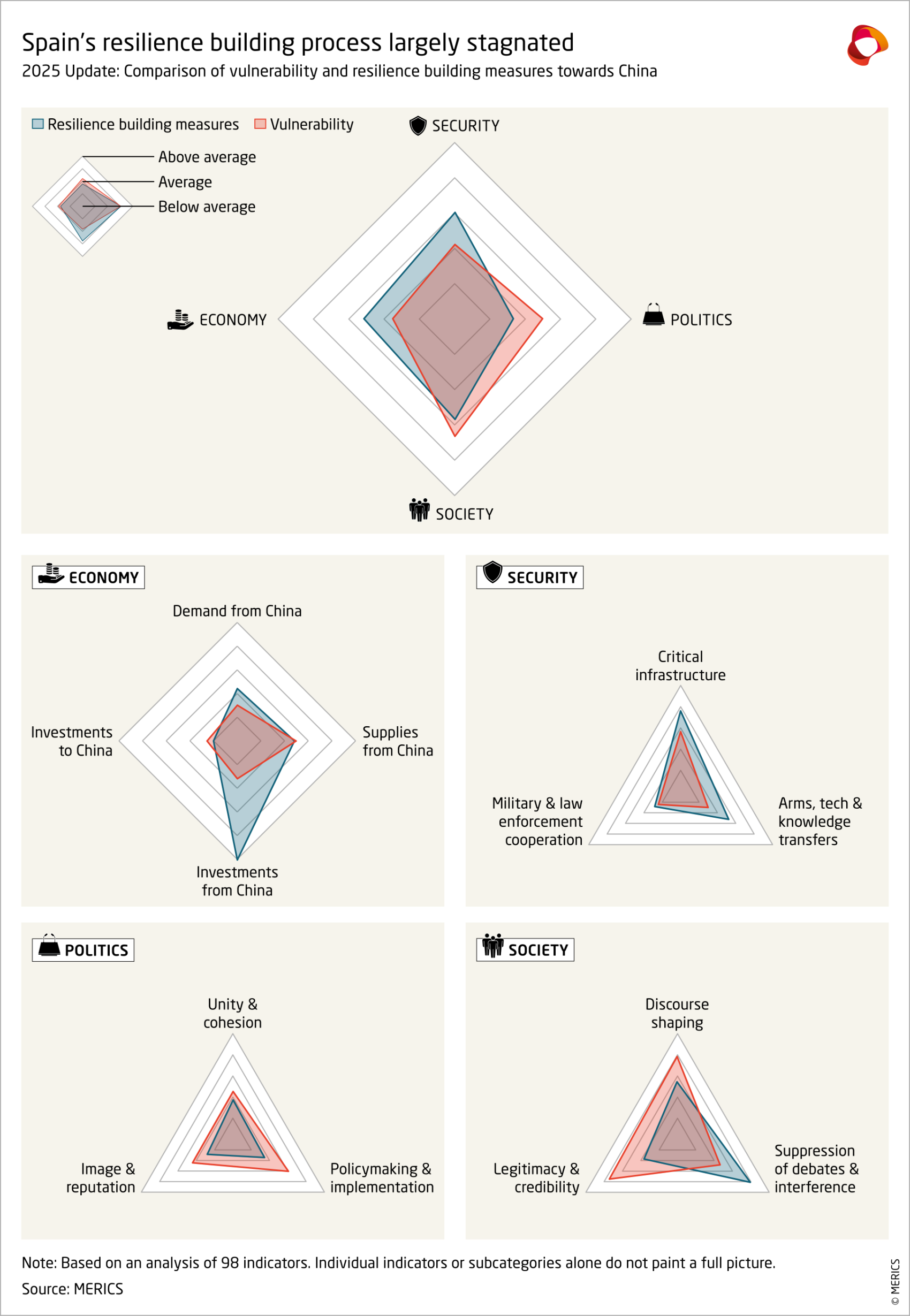

Spain–China Relations

The Spanish government has intensified engagement with China, primarily on economic issues. Spain’s External Action Strategy highlights center-left Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s three visits to China since 2023, emphasizing ambitions to build closer partnerships with Asia-Pacific powers. During his last China visit in April 2025, a new draft Plan of Action was adopted to reinforce the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, with trade, investment, agriculture, and science and technology as priority areas.

This shift towards reengagement is driven in part by Madrid’s efforts to attract Chinese greenfield investment. It marks a departure from Spain’s traditionally EU-centric China policy. Notably, Spain abstained in the EU vote on tariffs against China-made electric vehicles in 2024, despite having been an early supporter of the EU investigation. Similarly, Spain’s Ministry of Interior renewed a contract with Huawei to store recordings of court-approved wiretaps. It argued no security risks were involved, even though the EU Commission flagged potential interference concerns and the US expressed strong opposition.

Despite these efforts, Spain was targeted when China retaliated for EV tariffs. In June 2024, Beijing launched an anti-dumping investigation into European pork, hitting at Spain, the EU’s largest pork exporter to China. In September 2025, China imposed provisional tariffs of up to 62.4 percent, a measure that disproportionately affects Spain.

Key challenges for Spain

- Chinese companies are expanding in Spanish critical infrastructure, telecommunications, and technology. Spain has yet to publish a list of high-risk vendors under the EU’s 5G toolbox, enabling Vodafone Spain to renew its Huawei 5G contract, and the Ministry of Defense to recontract with Huawei for fiber-optic equipment although this move was later canceled under EU and US pressure. In addition, Origin Quantum (China) signed a cooperation agreement with ChinaLink ESGt to build a quantum computing power center, further adding to Spain’s critical infrastructure and tech exposure.

- Spain continues extraditions of Taiwanese nationals to China. Since the European Court of Human Rights’ 2023 ruling prohibiting Poland from extraditing a Taiwanese citizen, Spain has extradited at least one person, raising questions about its extradition practices.

- At EUR 4.2 billion, Spain recorded the highest level of prospective Chinese FDI in the EU in 2024. While Madrid has sought to stem economic vulnerabilities, deepening ties with China are heightening Madrid’s exposure to potential economic coercion.

How Spain stands out

Spain’s economy is outperforming many others in Europe, with the OECD forecasting national economic growth of 2.64 percent in 2025. Chinese companies have recently announced a number of large-scale investments—although Envision’s planned EUR 900 million electrolyzer plant has stalled since spring 2025. But Spain remains less exposed to China than most EU peers: Its exports to China account for only 0.6 percent of gross domestic product and Chinese direct investment made up just 0.9 percent of Spain’s total stock in 2023.

Spain is consolidating its leadership role in clean technologies – renewables have already reduced its energy dependence and stabilized prices. The Foreign Action Strategy 2025–2028 is meant to position Spain to benefit from the global shift toward renewables. But Madrid risks substituting one dependency for another if makes its clean-tech supply chains overly reliant on Chinese manufacturers that dominate the sector globally.

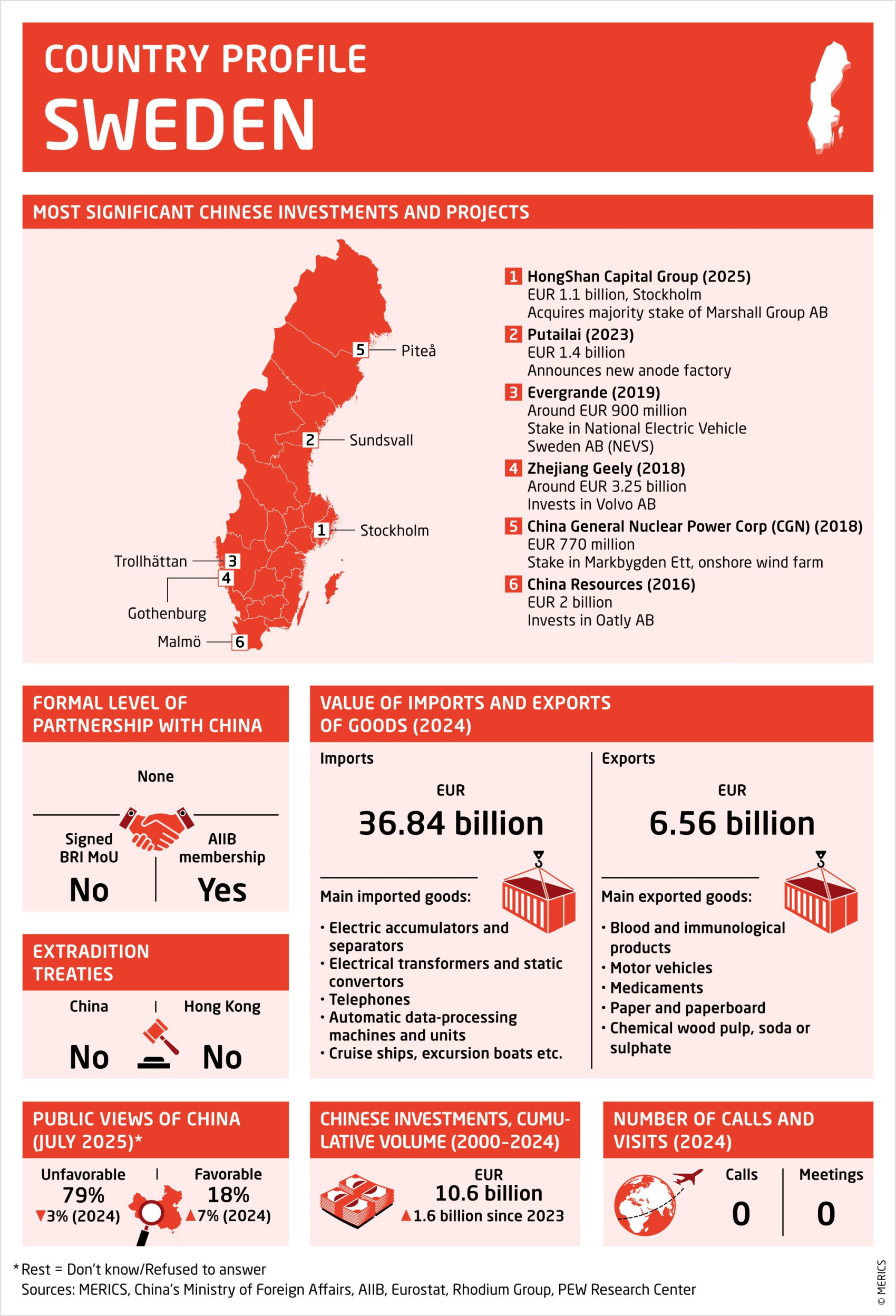

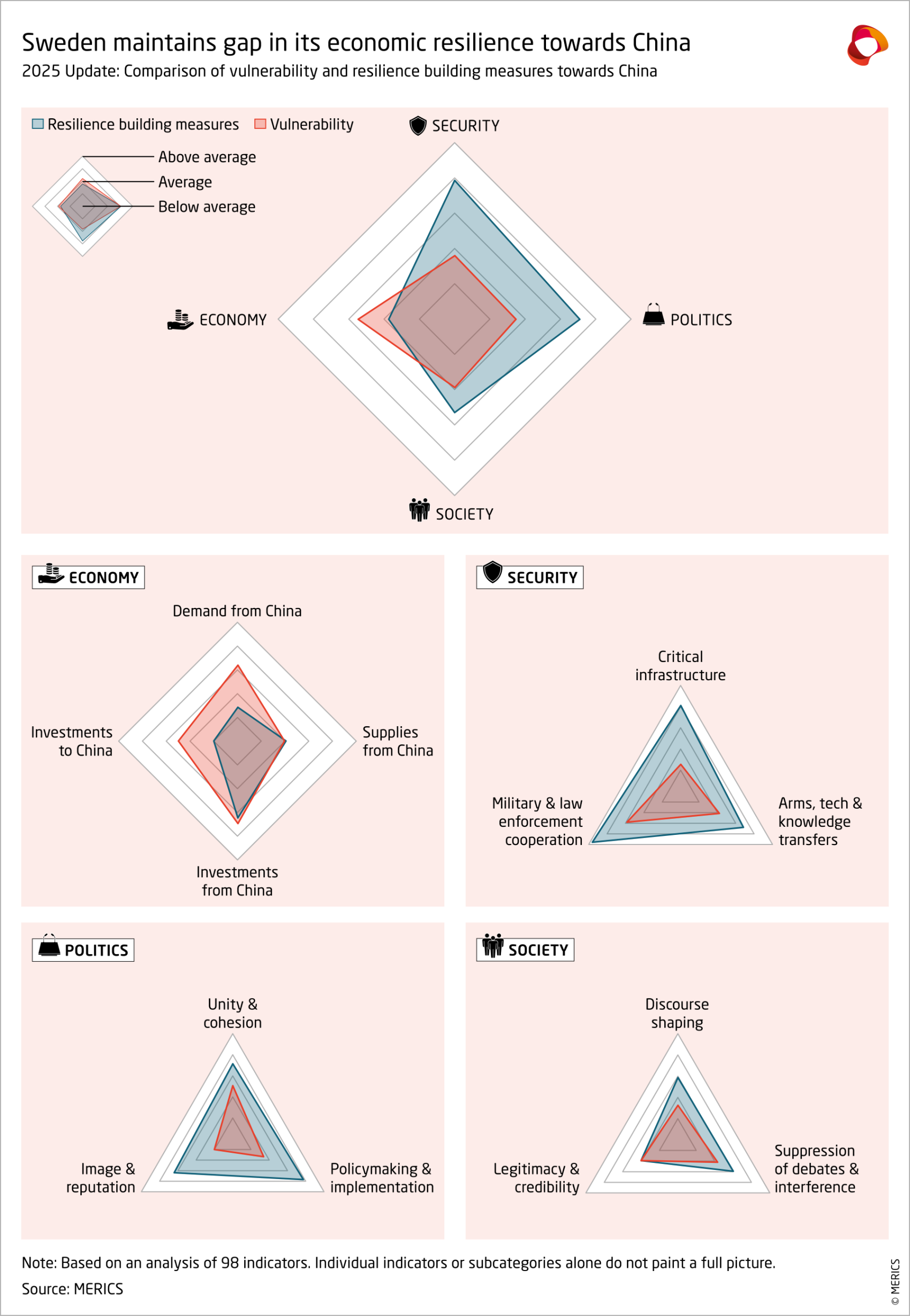

Sweden-China relations

Sweden has adopted a nuanced approach towards China. Following the release of its National Security Strategy in July 2024, Stockholm is seeking trade and investment ties with Beijing while also strengthening economic security and resilience.

But Swedish public opinion remains strongly negative. Distrust has grown since the 2015 abduction of Swedish citizen Gui Minhai and the ensuing deterioration of relations. According to a 2025 Pew Research Center survey, Sweden ranked among the top three countries globally—and first in Europe—for unfavorable views of China.

At the EU level, Sweden generally aligns with Brussels’ approach but sometimes pursues a different line. The EU decision in October 2024 to impose countervailing measures against Chinese electric vehicles was highly divisive. Sweden abstained, publicly voicing opposition – even as its foreign investment screening mechanism blocked a sensitive investment of battery materials producer Putailai (PTL) in March 2025. This reflects Stockholm’s gradual shift toward reducing dependencies and protecting national security – while still preserving elements of its long-standing commitment to liberal free trade.

After six years without top-level exchanges and repeated cases of Chinese economic and political coercion, Trade Minister Benjamin Dousa’s visit to Beijing in November 2024 marked a cautious resumption of high-level dialogue. The visit was followed up by trips of EU minister Jessica Rosencrantz and Foreign Minister Maria Malmer Stenergård to China in October 2025. This re-engagement trend was highlighted by the fact that the visits coincided with Swedish truck maker Scania opening a major manufacturing hub in China.

Key Challenges for Sweden

- Sweden is one of Europe’s strongest free trade advocates, sometimes bringing it into conflict with its support for the principle of economic security. Stockholm views EU tariffs—such as those imposed on Chinese EVs—as trade barriers, explaining its abstention from supporting the European Commission in October 2024.

- Chinese owned Volvo Cars is one of Sweden’s largest private employers, making it a major corporate vulnerability. The case of Ericsson, which lost market share in China after Sweden banned Huawei and ZTE from 5G networks in 2020, further illustrates the risks.

- The bankruptcy of Northvolt, Sweden’s flagship battery company and a key EU industrial project, highlighted Sweden’s lack of resilience through its dependence on Chinese machinery, materials, and critical raw inputs. Northvolt’s end raised questions about European clean-tech strategy and the challenges for national champions to scale up.

How Sweden stands out

Sweden‘s 2019 China Strategy continues to guide government policy, despite being prepared by a previous administration. Stockholm is committed to building up analytical capacity on China as shown by comparatively large number of China specialists think tanks and government bodies, and by creation of a dedicated, government funded Swedish National China Center.

Sweden resumed Prime Minister-level dialogue in July 2025 with a meeting between Kristersson and Chinese Vice-Premier He Lifeng. Its hosting of US–China trade talks in July 2025 signaled its credibility as a stabilizing actor in an increasingly tense world.

Despite negative public opinion and a history of Chinese political and economic pressure, Sweden is pursuing a nuanced approach, for example, allowing Chinese investment in non-critical sectors. This balancing act sometimes leads Stockholm to diverge from Brussels’ stance; it also highlights its policy’s pragmatism.

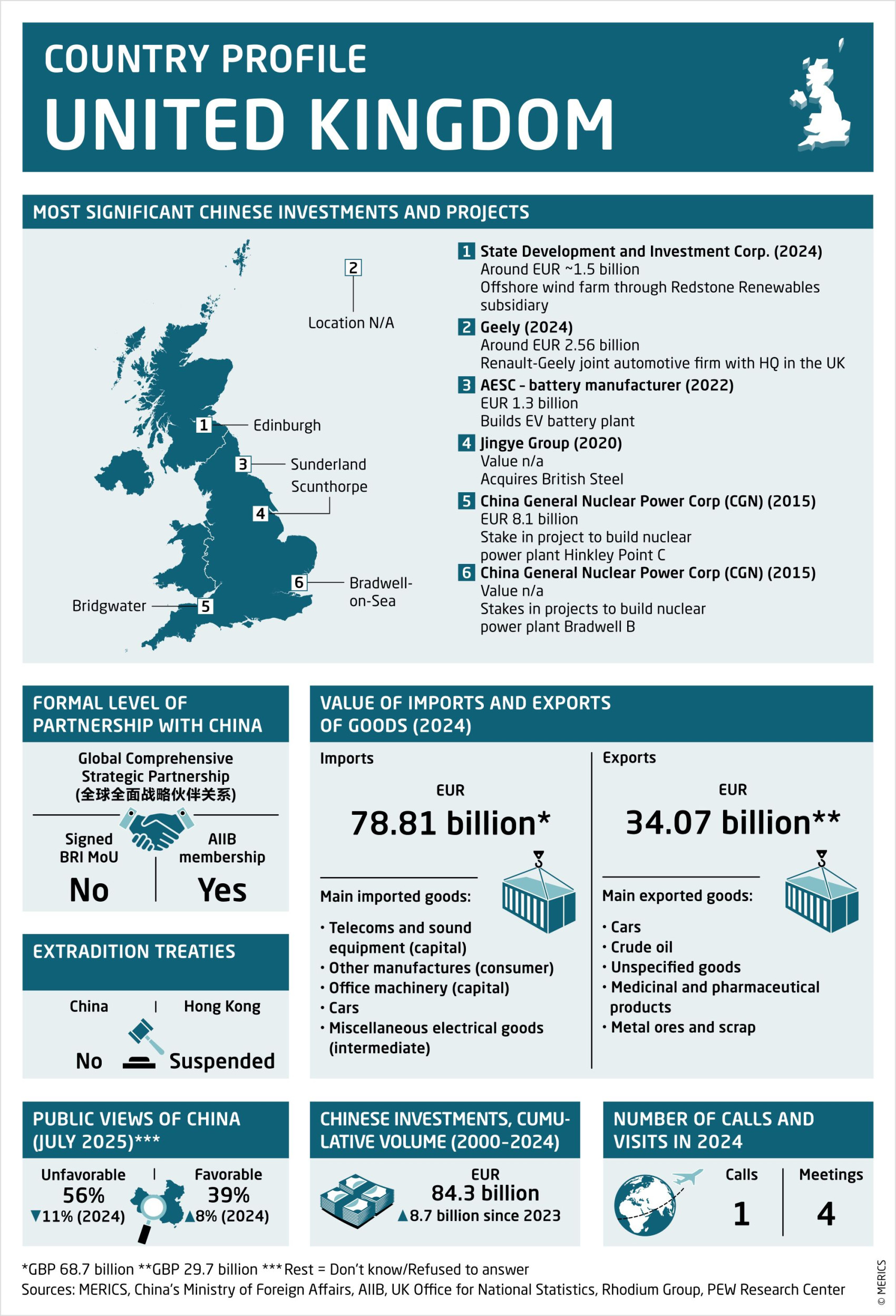

UK-China relations

The election of the Labour government in July 2024 marked a shift in UK-China relations after strains under the Conservative Party. Prime Minister Keir Starmer has revitalized engagement, reactivating the High-Level Economic and Financial Dialogue and Joint Commission on Trade and Economy, dormant since 2019 and 2018 respectively, and preparing to relaunch the Joint Commission on Science, Technology and Innovation, for the first time since 2021.

London undertook an audit of UK-China relations to assess their state and identify areas of potential cooperation and strategic vulnerabilities – also covering the latter in the new strategic defence review. The audit was concluded in July 2025 after several delays but was never published. It reportedly adopts what the government calls an approach of “progressive realism”, balancing investment needs with mounting concerns about national security and economic resilience vis-à-vis China.

The tension between the two objectives is already apparent. While still seeking to deepen economic ties, the Labour government over the past year has been considering the renationalization of British Steel from its Chinese owner, the expansion of UK intelligence capacity on China, and reviewing permission for China to build a huge new embassy in London, set to be its largest in Europe, amid growing concerns about espionage.

The situation is further complicated by international dynamics and relations with Washington. The April 2025 UK-US trade deal committed the Starmer administration to tighten scrutiny of supply chains and ownership structures, a move Beijing perceived as targeting Chinese companies.

Key challenges for the UK

- The UK’s screening of foreign investment remains among Europe’s least stringent, with high notification thresholds and narrow sectoral coverage. London has taken some steps to better protect its critical infrastructure by limiting Chinese involvement in nuclear power and steelmaking and aiming to phase out Huawei components in its 5G networks by 2027. But the comparatively lax system makes solutions more partial than systemic.

- UK economy is particularly exposed given trade and investment ties not only with Mainland China, but also with Hong Kong. British investment in both regions amounted to 4.2 percent of UK GDP in 2024 (0.5 percent with China and 3.7 percent with Hong Kong, compared to Germany’s 2.5 percent and 0.3 percent, respectively), while UK exports to China and Hong Kong made up 6.4 percent of all UK exports, close to 7 percent of overall exports value for Germany.

- While the UK has issued knowledge-security guidelines, its research is most exposed to misuse among countries tracking the problem. UK and Chinese institutions jointly published over 86,000 articles on critical technologies from 2010 to 2024.

- Hosting Europe’s largest Hong Kong diaspora, the UK is also highly exposed to Beijing’s repression of citizens living abroad. Dissidents living in the UK have been alarmed that the Starmer administration is thinking about reinstating its extradition treaty with Hong Kong, even if on a “case-by-case” basis. London suspended the treaty five years ago after Beijing passed its Hong Kong National Security Law, criminalizing acts of subversion or collusion.

- The UK has no tariffs on China-made electric vehicles (EVs) in place, despite being a major market for Chinese EV companies. For instance, it is the top European market for BYD, a key Chinese actor in this sector.

How the UK stands out

The UK stands out in its systematically structured commitment to building governmental capacity to deal with China, especially compared to its European peers.

Despite criticism over limited transparency and delays, its China audit offers lessons for other European states on monitoring the China-related activity of their government agencies. The Starmer administration also intends the audit to inform its upcoming industrial strategy – for example, by updating definitions of vulnerable sectors, expanding intelligence capabilities, and creating mechanisms to counter transnational repression.

The UK also stands out through its cross-governmental training and dedicated capacity-building programs regarding China. Institutions like the Great Britain China Centre have reportedly trained over a thousand civil servants recently. Plans outlined in the China Audit, disclosed to the UK Parliament, include launching a China Fast Stream for UK diplomats and expanding its global China network, which already operates through British embassies around the world.

UK lawmakers also keep the government on its toes. In 2024 they logged more than three times as many questions and interventions about China as their French colleagues, the second most active group of parliamentarians among the mapped countries.

| You were reading a chapter of the MERICS Europe China Resilience Audit. For a detailed report and further analyses, visit the project's landing page. |

This MERICS analysis is part of the project “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.