MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker 01/2023

Focus Topic

Chinese Forecasts for 2023: A worsening geopolitical environment

by Helena Legarda

One year after Russia launched its war against Ukraine, Beijing’s view of the international environment is gloomier than ever. The United States and its coalition-building efforts in the Indo-Pacific are seen as the biggest challenge to China’s stability and global ambitions. Largely due to this worldview, Beijing remains committed to its relationship with Moscow, even as Putin’s war of aggression drags on.

In the past year, China’s “pro-Russian neutrality” has proved not so neutral. Chinese SOEs have reportedly shipped military or dual-use equipment to sanctioned Russian defense firms,1 while President Xi Jinping plans to visit Moscow in the spring. Meanwhile, Chinese rhetoric presenting NATO and the US as drivers of this crisis continues unabated.

The signals coming out of Beijing offer no comfort to some in Europe who hope that Beijing will distance itself from President Putin, and that China may still be convinced to play a more constructive role in this crisis. Xi himself noted during his virtual meeting with Putin in December 2022 that their two countries must “maintain close coordination and collaboration in international affairs”.2

Beijing is likely to continue investing in its relationship with Russia, in the face of the worsening geopolitical environment and despite the tensions created. It does so partly as a hedge against worsening tensions with the US, European nations and other countries.

Western analysts and forecasters identify the continued deterioration of China’s ties with the West as one of the main risks facing Beijing in 2023. They also warn that Xi’s governance approach will be tested by the spread of Covid-19 within China and by the feebleness of China’s economic recovery.3

Below, we examine forecasts for 2023 from three Chinese organizations to build a fuller picture of the year ahead – the Center for China and Globalization (CCG),4 the Center for International Security and Strategy (CISS) at Tsinghua University,5 and the Center for National Security Research at Renmin University6 – and a number of individual high-profile experts.7 Their analyses are essential to understand what China’s top foreign policy thinkers expect in 2023, as they will help shape Beijing’s agenda and priorities.

Competition with the US will intensify

They paint a picture of a complicated geopolitical environment for China. The main risk, they say, is US-China competition. Most Chinese forecasts expect it to continue or even intensify this year. Certainly, 2023 got off to a difficult start as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Beijing was canceled after the discovery a Chinese balloon over the US landmass. The visit was intended to seek a framework for managing tensions.

Washington’s efforts to build a coalition of like-minded countries to contain China’s rise and pursue economic and digital decoupling are cited as major areas of concern. Several forecasts also focus on US domestic crises as risky for China and the rest of the world. Two key scenarios preoccupy forecasters: a US-driven global recession and domestic political polarization, with some experts warning that Washington might try to bait China into war as its global influence diminishes.8 This view rests on Chinese analysts’ assessment that the West is no longer the main driving force of economic growth and development globally. They put this down to the impact of both Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine.

Even so, none of the forecasts analyzed here expect an open conflict between the United States and China this year. The Xi-Biden meeting on the sidelines of the November 2022 G20 Summit in Bali is credited with having injected some stability into the relationship that may carry over into 2023. However, they were all published before the February spy balloon incident. This incident highlighted how strained US-China relations have become and the lack of trust between them. Although not enough to kill their wish to stabilize the relationship, it has certainly disrupted the process.

Hard security risks are increasing

The United States is omnipresent in discussions about some of the key hard security challenges facing China this year. Most experts see a “frozen conflict” in Ukraine as one of the top issues that Beijing will have to deal with in 2023. Washington is identified as the main cause of the crisis and a major beneficiary of its continuation: one Chinese expert openly called the conflict a proxy war, using language that goes beyond official rhetoric that skirts around the accusation.9

China is seen as relatively unaffected by any direct impact from the war, but Chinese analysts point to many linked concerns – Europe’s closer alignment with NATO and the United States; a stronger NATO; renewed Western interest in the Indo-Pacific; and more costly oil and gas imports.10 Many Chinese experts call on Beijing to take a more active role in promoting peace talks, though the consensus is that China’s position on the issue will not shift. Neither will its close relationship with Russia. This will therefore reduce the likelihood that Beijing may in fact take on a more constructive role.

Tensions in the Taiwan Strait are also listed among 2023’s challenges, though a far less important one than last year. The situation is expected to remain stable, though a potential visit to Taiwan by the new US Congressional leadership is identified as a potential trigger for another flare-up.11

Finally, some predictions warn nuclear tensions could escalate in Northeast Asia due to the current dynamics on the Korean peninsula.12 To be sure, North Korea is not seen as the responsible party behind this potential crisis. Instead, the US, Japan and South Korea are seen as the culprits, due to their failure to consider North Korea’s security concerns and their unreasonable response to China’s rise. It is an account that reflects Beijing’s persistent view of the United States as its main adversary and a driver of instability.

Global economic slowdown will fuel decoupling

Chinese experts share a negative view of the global economy this year, as inflation, the energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine, and a general economic slowdown are expected to hit all major economies. China is seen as being better placed than most to weather this crisis, but forecasters predict more protectionism, greater securitization of supply chains and a bigger push towards decoupling by Western countries, which will hurt China’s economy.13

A potential economic slowdown in China, though seen as unlikely, is cited as a potential risk to domestic stability. Like the wave of Covid-19 infections after the country reopened, a weak economy is seen as something that could shake public confidence in the party-state’s governance model, opening opportunities for “Western ideological infiltration.”14

In keeping with the official line, the Covid-19 pandemic has lost much of its weight as a challenge for China in 2023. Most forecasts appear optimistic about China’s reopening. Among the few issues of concern raised were global access to medical resources and the possibility that new mutations may enter China from abroad.15

The way forward: China’s priorities in 2023

The forecasts examined here outline how Chinese experts see Beijing’s way forward in 2023. According to them, China-US geopolitical competition will remain center-stage in shaping China’s foreign policy, though they advocate preserving stability in the relationship. US-China tensions have become a permanent feature of Chinese assessments of the external environment. Strengthening ties with developing nations is also seen as a priority, partly to foil any attempts to contain China by the United States and its allies. Ex-foreign minister Wang Yi (who is now Director of the Office of the CCP Central Foreign Affairs Commission) echoed this approach in his review of his ministry’s foreign policy priorities for 2023.16 The policy areas and issues to watch this year therefore are:

- Attempts to stabilize China-US relations: Beijing will try to smooth over tensions caused by its continued support for Russia and the spy balloon incident in February. It will seek to restart communication and prevent tensions from escalating. But a fundamental change in approach is unlikely.

- Continued support for Russia: China-Russia relations are likely to remain strong, as Beijing has committed to deepening its “mutually beneficial cooperation” with Moscow. This may extend to limited economic and material support for Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. This would help Moscow to sustain the war effort and stay away from the negotiation table.

- Outreach to developing countries: Beijing will also focus on deepening ties with developing nations by presenting China as a reliable partner that does not interfere in domestic issues. Beijing will leverage its Global Development and Global Security Initiatives (GDI and GSI) to build a China-centric network of countries to support its global governance reform ambitions.

- Defense of China’s core interests: Beijing seems likely to push back even more aggressively against any attempts to infringe on China’s “sovereignty, security and development interests”. Developments that involve either Taiwan or the US presence in the Indo-Pacific are the most likely to trigger forceful responses.

- Strengthening China’s messaging and foreign affairs legislation: Beijing will continue to strengthen its international communication capacity to “tell China’s story well”. New legislation strengthening Beijing’s extraterritorial reach and its ability to retaliate against Western sanctions, or unilaterally impose its own, can also be expected.

- Improving relations with Europe: Europe seems to have become less of a priority, though Beijing will continue efforts to pull it away from the United States and to get relations back on a positive track. China’s ongoing diplomatic charm offensive reflects these ambitions, but it would be unwise to see it as signaling a permanent policy shift.

China faces a difficult year as international challenges are compounded by domestic crises, including a decelerating economy and rising Covid cases. In 2023, the CCP will have to find a balance between preventing instability domestically, and projecting strength internationally to support goals set out at the 20th Party Congress last October. However, with geopolitical competition front and center, tensions between China and the United States, or with Western countries more broadly, are unlikely to diminish.

Key Developments of the quarter

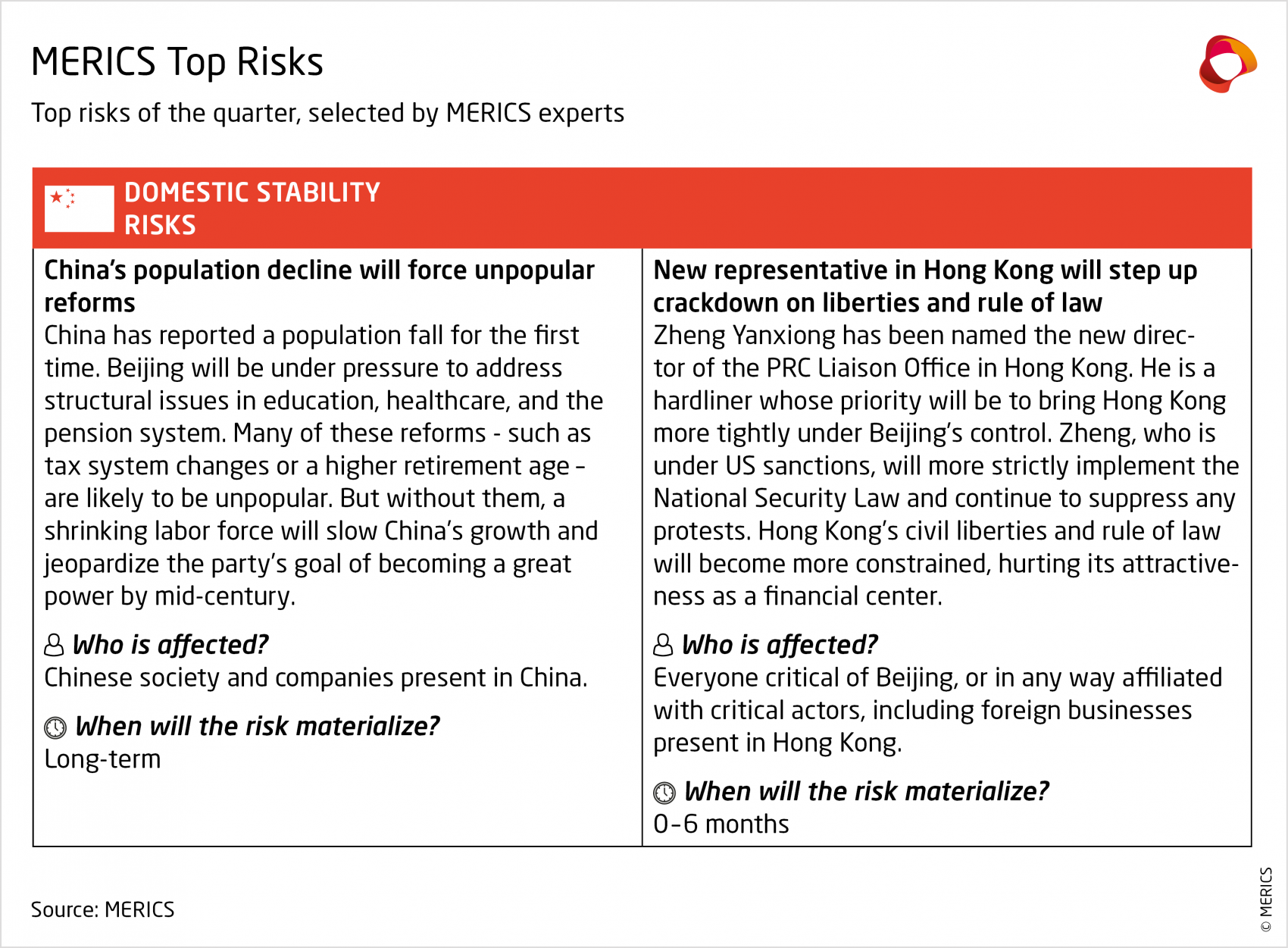

Domestic Stability

China’s snap turn on zero-Covid highlights cracks in the healthcare system

Public finances in China, especially local healthcare, are under pressure. Drastic, and expensive, lockdown measures have already drained the coffers of less affluent localities. Now, a surge in Covid patients is straining the health care system further. Clinics, especially in poorer area, are struggling with the lack of ICU beds, shortages of antiviral drugs and poorly coordinated procurement of foreign supplies.

Hospitals have been working at capacity – or above – since early December. Experts predict mass travel for Chinese New Year holidays may lead to rolling Covid waves for weeks to come. It is becoming clear how much Beijing has neglected healthcare reforms and underfinanced local healthcare infrastructure over the last few years.

Among the population, bewilderment followed relief after the sudden turn on zero-Covid. Beijing’s Covid strategy is again drawing strong criticism as the death toll mounts. Officially-recorded Covid deaths have exceeded 70,000 since December, and the figures are likely an underestimate. Lack of preparation for unlocking means people face scalper prices for coffins and cremation, and black-market prices for essentials such as ibuprofen are sky high, leading to public outcry. Beijing’s rapid switch from warning of the severe danger of the virus to encouraging people to work even while sick has many people calling out poor governance.

China’s government is under systemic stress, laid bare by a weak healthcare sector, poor public finances in already cash-strapped, low-income areas, and scant public trust in its handling of the outbreak. Keeping the under-financed healthcare system afloat will be priority in the coming months, not least to keep public protests in check.

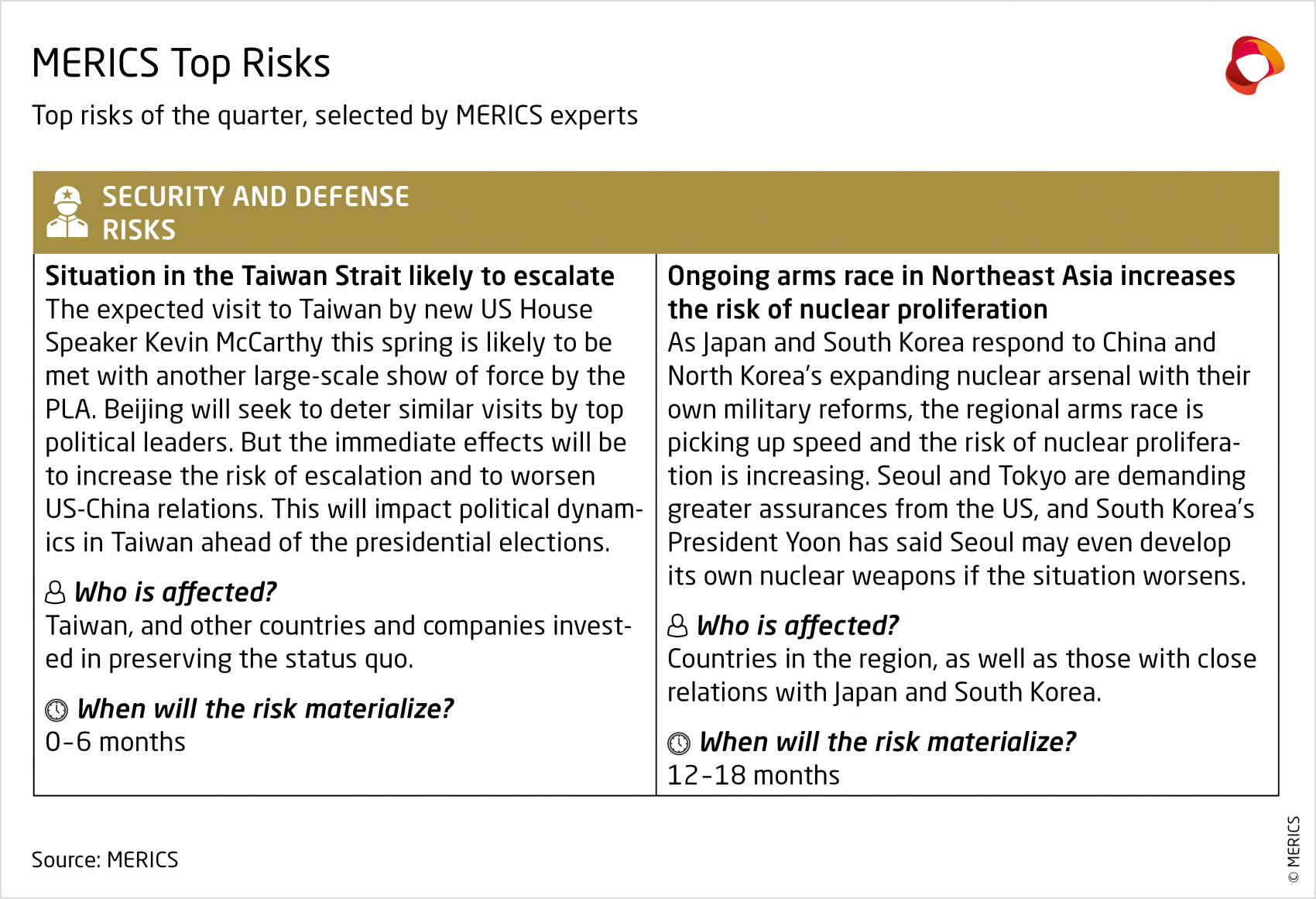

Security and Defense

Instability in South Asia hits China’s interests and investments

Chinese citizens and companies face growing security threats in South Asia as the country reopens after almost three years of Covid-induced isolation. Border clashes between China and India continue and the situation is also deteriorating in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The volatility is likely to impact the development of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2023, its tenth anniversary.

Over the last two months, Chinese nationals have been the target of at least two terrorist attacks in Afghanistan claimed the by Islamic State Khurasan Province (ISKP) terrorist group. ISKP has long been critical of Beijing’s crackdown on the Uighurs in Xinjiang and its support for the Taliban. But the bombings mark a new step in ISKP’s attempts to target Chinese interests in Afghanistan and damage the Taliban regime’s attempts to secure international recognition and investment.

Meanwhile, protests against the expansion of the Gwadar Port in Pakistan – a key node on the BRI – escalated again in January. Protesters staged a sit-in, blocking the port and demanding the departure of the roughly 500 Chinese nationals who work there. The protests are not exclusively about China’s development of the port, but preferential treatment of Chinese citizens and the excessive number of security checkpoints are among the main causes of anger.

Protecting China’s overseas interests is gaining in importance for the government and the public in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This uptick in instability in the region is sure to be stoking fears in Beijing. First, the BRI and other investments could be disrupted and, second, there is a greater risk of instability or terrorism spilling over into Chinese territory. For now, Beijing is unlikely to abandon the region, especially Pakistan, due to its strategic location along the BRI. Instead, it will try to pressure local governments to guarantee the security of Chinese citizens and assets. But the CCP remains a risk-averse actor that will do its utmost to avoid becoming too involved in regional conflicts. If local governments fail to provide the promised security, Beijing will look for alternative investment destinations and sources of natural resources. Such moves could increase competition with Europe in Africa, Latin America and other regions.

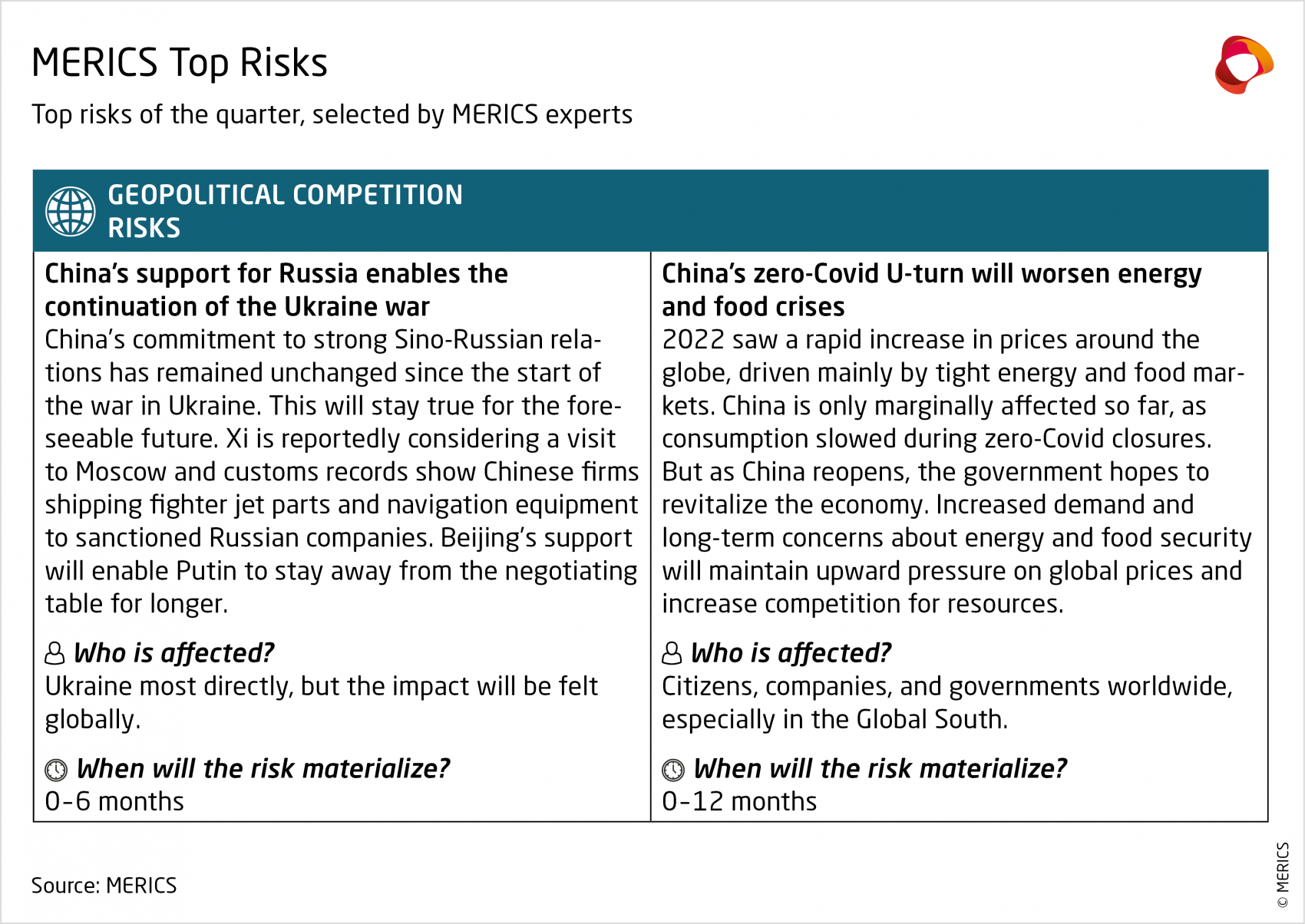

Geopolitical Competition

China’s reopening will increase competition for energy resources

China’s leadership has emerged from the 20th Party Congress quick to offer a conciliatory diplomatic tone. Xi kicked off the charm offensive at the G20 Summit in November, seeking to stabilize relations with the West. However, Beijing’s gestures do not herald a fundamental change in policy as its core interests have not changed. Competition with the United States and Europe will continue.

This holds true for energy security, which is one of Beijing’s key concerns due to the global energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine. Over the last two months, Xi and newly appointed foreign minister Qin Gang have stepped up their engagement with the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia to secure natural resources for China’s growing energy needs. This engagement has netted Beijing a USD 60 billion, 27-year deal with Qatar for liquefied natural gas (LNG), as well as an oil extraction deal with Afghanistan’s Taliban government.

All this took place against the backdrop of Beijing’s scrapping of zero-Covid policies and the ongoing war in Ukraine, which has caused a far greater energy crisis in Europe. So far, European countries have held up well this winter, with energy prices easing and gas storage at comfortable levels. But tougher times could lie ahead.

Prior to its Covid turn-around, China had subdued demand for oil and gas and was able to meet increasing portions of it with Russian imports. China even re-exported excess supplies to Europe. But as China reopens, consumption is likely to pick up, driving up factory activity and economic growth more broadly. China, a net energy importer, will therefore see increased demand for natural resources. China’s demand cannot be satisfied by Russia alone, so a scramble for energy supplies and rising prices in international markets may follow.

Beijing’s determination to make sure energy shortages do not obstruct economic growth means European countries must increasingly factor China into their energy security policies. This applies both to competition for oil and gas contracts, and to Europe’s green transition. China’s growing energy needs and its strong position in green supply chains highlight Beijing’s dual roles as a competitor and an unavoidable partner for the EU.

Economic and Tech Security

Economic downturn is putting a strain on people’s trust in the CCP

China’s gross domestic product (GDP) increased by a mere 2.9 percent in 2022, far below its own 5.5 percent target, and one of its worst results in nearly half a century. Unemployment increased overall, with young people hard hit by unemployment rates among 16-24 year olds of 16.7 percent in 2022. The downturn was fueled by severe Covid-19 restrictions, rolling lockdowns, anemic consumption, and a slumping housing market.

The property market accounts for roughly 30 percent of China’s annual GDP and is in a deepening crisis. For many Chinese, owning property is one of the only ways to invest and grow their capital. Investors who viewed property as a reliable investment a few years ago are now uncertain about the future of their assets.

The strength of China’s economic recovery in 2023 is uncertain. It will benefit from a lower base from 2022 and pent-up demand may support growth. Yet, the external environment could complicate things if the United States further restricts technology flows, or a global downturn impacts China’s export demand.

These economic developments will increase the socio-economic pressure on the government in 2023. They corrode the unspoken social contract between the party-state and the people that promises increasing prosperity in exchange for political passivity. While a widespread movement against the current leadership is highly unlikely, the CCP will have to rack up some major successes to shore up the confidence of Chinese citizens. This will be tricky in an increasingly uncertain external environment. The additional pressures on the party-state and on society at large could lead to miscalculation. Internationally, a weak Chinese recovery would likely drag down global growth at an already economically bearish time, and might even contribute to a major downturn.

Europe is caught in the crossfire of the ongoing US-China tech war

US export restrictions have disrupted global semiconductor supply chains. Targeted bans on high-end semiconductor chips have affected chipmakers across the world, as well as makers of chip manufacturing equipment and technologies. The Dutch firm ASML is an example of the impact on European companies. Sales of lithography machines to China will tumble, given the January agreement between the Netherlands, the US and Japan to curb the export of chipmaking equipment.

Similar restrictions may arrive in sectors such as quantum information science, biotechnology and AI algorithms, indicated Alan F. Estevez, the US Under Secretary of Commerce for Industry and Security. If so, it will likely accelerate trends towards high-tech decoupling, as companies adapt to US restrictions. Europe can ill afford to continue without a concerted strategy.

Quantum may well be the US’ next target, given its broad applications and China’s recent advancements. Baidu announced its first quantum computer in October 2022, and a team of Chinese researchers recently made the startling announcement of a new method that could break RSA, a widely used web encryption scheme.

There are few signs that US-China tech competition will cool off any time soon, regardless of the positive Xi-Biden meeting on the sidelines of the November G20 summit or other signals that the US and China are looking to stabilize their relationship.

Looking forward

What to watch in the months ahead

- 5 March 2023: Beijing will host the annual Two Sessions meetings – a gathering of the National People's Congress (NPC) and the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). Major government reshuffles will take place in line with the decisions of the 20th Party Congress, and the 2023 government budget will be announced.

- April 2023: French President Emmanuel Macron is due to visit Beijing in early April. He is expected to try to encourage Xi to play a more constructive role in the Ukraine war and distance himself from Russia’s President Vladimir Putin.

- Spring 2023: Germany’s China strategy was scheduled for release before April, in the wake of the new national security strategy unveiled at the Munich Security Conference in February. However, it has been delayed, amid internal disagreements over what direction to take.

- 19-21 May 2023: The G7 Summit will take place in Hiroshima, Japan. The summit is likely to focus on the war in Ukraine, and on the global energy and food security crises that have been worsened by the war. But given the host’s priorities, leaders are also expected to discuss the regional security situation in the Indo-Pacific, including China’s military buildup and North Korea’s nuclear program.

- Endnotes

-

1 https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-aids-russias-war-in-ukraine-trade-data-shows-11675466360

2 https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202212/t20221230_10999132.html

3 https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/china-forecasts-2023-dont-expect-too-much-chinas-re-engagement

4 http://www.ccg.org.cn/archives/73192

5 https://ciss.tsinghua.edu.cn/info/yjbg/5755

6 https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_21611597 ; https://www.163.com/dy/article/HRMD87PM055361IA.html

7 Chen Xiangyang, Director of the Institute of World Political Studies at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), http://www.cicir.ac.cn/NEW/opinion.html?id=09a085b9-cfc7-4c65-876c-4a9c08994220; Jin Canrong, Professor and Associate Dean of the School of International Studies at Renmin University, http://www.cssn.cn/gjgc/gjgc_gcld/202301/t20230102_5577302.shtml; Chen Wenling, Chief Economist of the China Center for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), http://www.cciee.org.cn/Detail.aspx?newsId=20376&TId=683; Zheng Yongnian, Director of the Institute for International Affairs at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), https://www.aisixiang.com/data/140018.html; Wang Wen, Executive Dean of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University, http://comment.cfisnet.com/2023/0112/1327195.html; Xu Bu, President of the China Institute of International Studies (CIIS) and Secretary General of the Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy Studies Centre, http://cn.chinadiplomacy.org.cn/2023-01/11/content_85054337.shtml

8 Wang Wen, Zheng Yongnian

9 Zheng Yongnian

10 CISS, Xu Bu

11 CISS, CCG

12 CISS, CCG, Zheng Yongnian

13 Center for National Security Research at Renmin University, Chen Wenling

14 Wang Wen

15 CISS

16 https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202212/t20221225_10994828.html ; https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/zyxw/202301/t20230101_10999543.shtml ; https://www.mfa.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202212/t20221225_10994818.shtml