China's slow path towards science and technology leadership

Scientists know their country is not yet a global leader in science and technology, says Kai von Carnap. This is the fifth in a series of short analyses that looks at China’s systemic competition and normative rivalry with the US and the EU. A look beyond the Beijing leadership shows how far debates about the features of political systems and the power to interpret events reach into Chinese society – and possibly shape the country’s actions.

To lead the next industrial revolution, China has placed what it calls “industries of the future” at the heart of its economic aspiration. It wants to leverage “the strength of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”, and Xi Jinping himself has often talked about wielding China’s “magic weapon” (法宝) to “concentrate power on great tasks.” In 2021, the 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) and a series of reforms showed what this means in practice: more money, “military order“ (军令状) for science and technology (S&T) management, 15 new major research projects, and a revamped Science and Technological Progress Law.

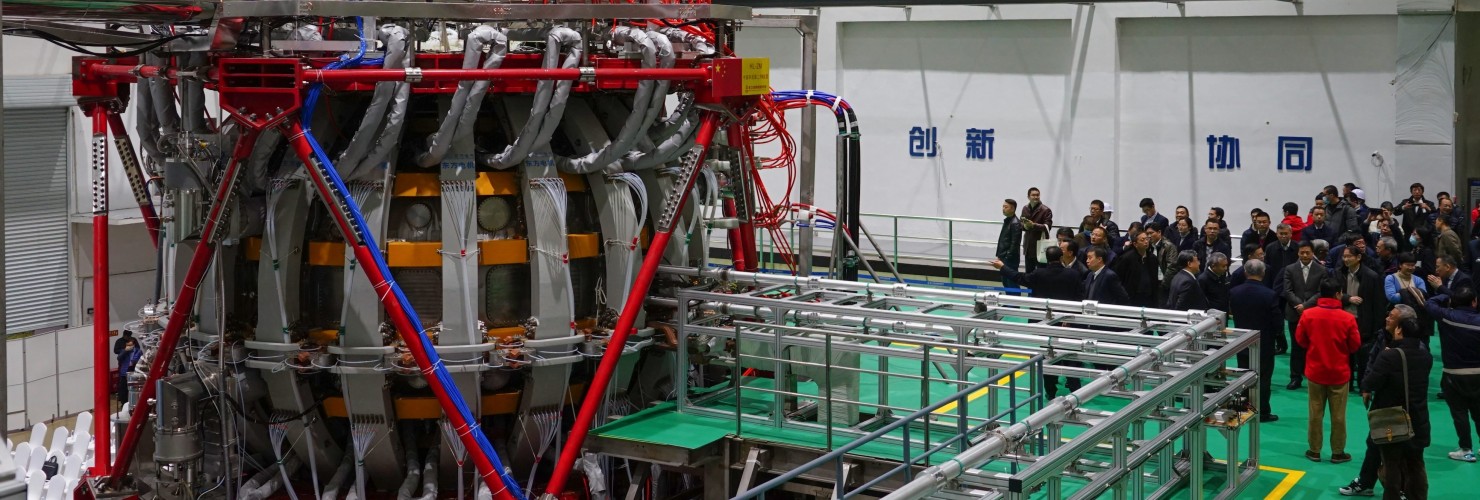

But not all scientists are convinced this is enough to meet China’s future-industry ambitions. In a popular article, renowned physicist Wang Yifan called for strong independent innovation capabilities to “win the fierce international competition.” He lamented that Chinas S&T system currently “cannot produce significant results” because research funding was lagging behind the US and EU and its allocation was inefficient. He called for the government’s funding of basic research to be raised from 5 to 10 or even 15 percent of overall R&D expenses and focus more on large research facilities and “big science” projects (大科学) – like the US’s Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb in 1945.

Enabling technologies and the industrial foundation are the main obstacles

Even China’s elite admits the country is still weak in enabling technologies and aspects of basic research. Minister of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) Xiao Yaqing recently underlined the need to tackle the long-standing issue of “technological bottlenecks” (卡脖子) around key core technologies (核心技术) and identified them the causes for Chinas “weak industrial foundation” in S&T. This is sensitive issue, as it was Xi himself who said in 2019 that global competition means “key core technologies cannot be obtained, bought, or negotiated” (要不来、买不来、讨不来) to ensure economic and defense security.

Introducing a report about Chinas S&T talent pool in August 2021, Chen Baoming, deputy director of the Talent Center of the Ministry of Science and Technology, spoke of structural deficiencies in how China develops S&T expertise and a persistent lack of personnel. He pointed out that, in 2019 there were only 27.2 researchers in R&D per 10,000 population, largely concentrated in the economically more advanced eastern regions. Developed countries, like South Korea and Denmark, Chen added, boasted more than three times that number. Overall, he admitted, "the investment intensity of R&D personnel is still low.”

Crucially, these deficiencies appear to be widely recognized and lead most experts to justifying the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) top-down approach. Wang Binglin and Sun Cunliang, scholars from a state research center, have explained that, ultimately, the Chinese system developed S&T exclusively in the interest of the people. That has been on display since “planned science”-projects, such as “two bombs and one star” (两弹一星) to develop home grown atomic and hydrogen bombs as well as a satellite, in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Scholars are beginning to see successes in S&T as the fruit of CCP leadership

Thanks to such projects, Wang and Sun pointed out, China’s income per capita since 1980 has risen from 171 yuan to 28,000 yuan, freeing 740 million people from poverty. Scholars are beginning to see successes in S&T as the fruit of CCP leadership. Projects like the Chang’e lunar rover were only possible under the CCP’s strong guidance, which creates an “organic balance” between competing interests. Qu Qingshang (曲青山), dean of the Resesarch Institute of Party History and Literature, has insisted the CCP is the best manager of society because it ensures the rule of law and equality amongst all ethnic groups.

This leads influential voices to conclude that S&T success can only continue under the CCP. Ren Ping, son of Huawei-founder Ren Zhengfei, provides a good example of the thrust of such arguments. Without the leadership of the CCP, he wrote in the People’s Daily, successes like “two bombs and one star” and the Chang’e mission would not have been possible. By this logic, having a strong party leadership is Chinas biggest advantage (最大优势) and the leadership’s authority must therefore be protected in all aspects of national governance, including science. Weaknesses in S&T justifies one-party rule.

Academic freedom is not palpable in practice

But strong leadership is seen to by some be impoverishing China’s intellectual environment. Zheng Lei, vice president of Hefei University of Technology, in 2021 demanded that scientists “should be encouraged in their freedom to conduct research even if its unpopular and based on their own personal interest.” On paper, scientists enjoy the leadership’s support – Xi has stressed the need to respect the spontaneous inspiration of scientists and to allow them freedom for their experiments and hypothesis. Yet with outspoken and critical academics – such as Zhang Qianfan or Xu Zhangrun – facing immediate judicial consequences for thinking aloud, such academic freedom is not palpable in practice.

How much S&T projects help improve the lives of normal individuals remains unclear. Big science and basic research can take years to bring any palpable economic results. Despite all its S&T successes, China is seeing income inequality rise again and still has some 600 million people earning about CNY 1000 a month (EUR 140), as Premier Li Keqiang recently pointed out. China has raised basic research funding from 6 to 8 percent of all research funding, or USD 30 billion a year, in the 14th FYP. But this is still a fraction of the USD 100 billion the US spends annually. S&T lacking personnel and rich in “military order” that undermines academic freedom will not be enough to compensate –¬ as Chinese experts appear to know.

Acknowledgements

This analysis is part of a series supported by a Ford Foundation grant and is licensed to the public subject to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.