Germany-China + Strategic Autonomy + Climate cooperation

TOP STORY: Germany is attempting to de-escalate EU-China tensions – why and at what cost?

Five weeks have passed since the EU sanctioned China because of human rights issues in Xinjiang. The Chinese reaction was harsh and asymmetric. But the only official statement from the German government was: “We have taken note of China’s reaction”.

Apart from that, nothing – not in the press release following German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the beginning of April, nor in the press release following the trilateral video call between Macron, Merkel and Xi. There has been no mention in Merkel’s speeches before the German Bundestag or any other occasion.

Now, at the end of April, it is time for inter-governmental consultations – a privileged format Germany only uses for very few nations. So far, the only mention of human rights since the sanctions has been from Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, and all he said was that the European Union has made its position clear on this matter and the topic will be – as always – discussed at the inter-governmental consultations. It appears to be business as usual.

This business-as-usual approach by the German side is notable also because European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and the EU’s High Representative Josep Borrell supposedly have just pointed out in a letter to the EU leaders that China is undergoing an “authoritarian shift”. The EU and China have “fundamental divergences” and “differences must not be brushed under the carpet” they argued.

De-escalation strategy – the German position

The very low-key strategy of Merkel’s government is a counterpoint against the European Union’s efforts to pursue a balanced but assertive approach. It could give China the impression that Germany does not take the EU sanctions as seriously as other European countries, and this might tempt China to apply its “divide et impera” strategy.

There are several possible reasons why Germany has opted for de-escalation. First, it could be hoping to use its existing communication channels to discuss possible concessions. One goal could be China’s ratification of the International Labour Organization’s forced labor convention.

Second, certain sectors of the German economy, such as the automotive industry, are highly dependent of the Chinese market. In 2020, Germany exported goods to the value of almost 96 billion EUR to China. There might be fears on the German side that tough words could harm the economic relationship. The fear is not unfounded – China targeted the Swedish fashion company Hennes & Mauritz with a boycott after it announced it would no longer use cotton from Xinjiang.

Third, Germany might want to send a signal to Beijing that the EU needs to balance assertiveness and cooperation with China – Europe votes for sanctions but continues to engage in a constructive dialogue. If China does not concede, Europe would move closer to the US position.

A less benign interpretation could be that Germany’s top leadership does not really support the European sanctions and is seeking further benefits for its privileged bilateral relationship.

A unanimous European Union?

For years European politicians and diplomats have called for a united approach towards China. German de-escalation and the trilateral video call between Macron, Merkel and Xi point in another direction. It is unclear why Macron and Merkel decided to use the trilateral format instead of including the EU Commission to discuss climate issues with Xi. They might hope that a Franco-German alliance produces quicker results. While Eastern European countries are calling for stronger alignment with the United States, Berlin and Paris are marching in a different direction – a dangerous divergence, because it risks the united approach.

Read more

- The Federal Chancellor [DE]: Chancellor Merkel exchanged a phone call with Chinese President Xi

- The Federal Chancellor [DE]: Chancellor Merkel speaks with the Presidents of France and China, Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC: Xi Jinping Talks with German Chancellor Angela Merkel on the Phone

- Federal Foreign Office’s Twitter [DE]: Video statement by German Foreign Affairs Minister Heiko Maas

- Politico: EU slams China’s ‘authoritarian shift’ and broken economic promises

“Correct choice” on strategic autonomy: What China wants from the EU

Strategic autonomy is a loosely defined policy concept, whose precise meaning the EU struggles to communicate clearly. Broadly, it revolves around the bloc increasing its strategic capabilities. Beijing has, in a number of diplomatic exchanges over the past few months, voiced its support for the EU’s strategic autonomy (战略自主). According to Chinese readouts, this was the message also delivered by President Xi Jinping in post-sanctions exchanges with European leaders.

In his call with German Chancellor Angela Merkel on April 7, Xi expressed hopes that “the EU will make the right judgment independently and truly achieve strategic autonomy” (希望欧盟独立作出正确判断,真正实现战略自主). During the video conference with Chancellor Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron on April 16, Xi spoke of the need to “firmly grasp the general orientation in the development of EU-China relations from a strategic heights” (要从战略高度牢牢把握中欧关系发展大方向).

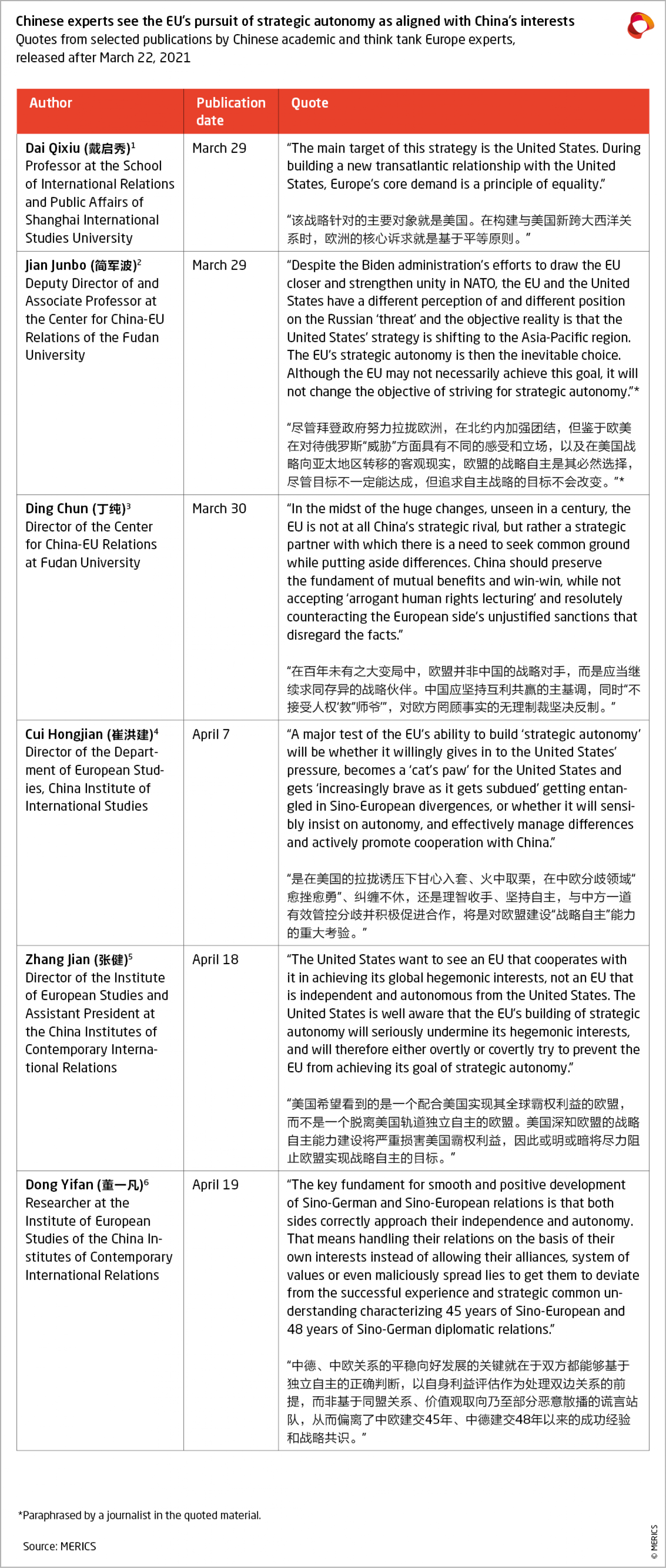

In the aftermath of the exchange of sanctions on March 22, a number of prominent Chinese Europe experts commented on Europe’s strategic autonomy. Their perspective sheds light on the mainstream Chinese vision for the EU-China relationship and its future

EU strategic autonomy as seen from the Chinese perspective

Chinese experts tend to characterize Europe’s goal of strategic autonomy as preventing the “state of total dependence on the United States” (对美国的全面依赖状态). The United States, in turn, is seen as “overtly and covertly trying to prevent the EU from achieving the goal of strategic autonomy” (或明或暗将尽力阻止欧盟实现战略自主的目标). Merkel’s and Macron’s comments about the absence of full alignment between European and US interests are frequently cited as proof that the EU is pursuing “the third way” (第三条道路) amid US-China tensions.

According to this logic, maintaining cooperation with China as a counterbalance to the United States is a necessity for the EU. Its internal challenges, exacerbated by the pandemic, increase the importance of maintaining strong economic relations with China. Sanctions and the EU’s tensions with Beijing are, therefore, “repeatedly emerging deviations from policy towards China” (在对华政策上屡屡出现偏差), which, China hopes, will not disturb strategic considerations. De-escalation and maintaining the status-quo in EU-China relations appears to be achievable, according to this view, as long as the EU remains committed to increasing its autonomy.

Trajectory and directions

Given that such an assessment appears to be shared by the top Chinese leadership, China is likely to remain confident about its position of strength vis-à-vis Europe, seen by Beijing as a geopolitically dependent actor. It will also continue to attempt to leverage ambiguities in the EU’s concept of strategic autonomy to prevent alignment on China between transatlantic partners.

Seen in this light, it is easier to interpret China’s harsh retaliation to EU sanctions and the increased intimidation attempts on the part of Chinese diplomats in Europe. Beijing’s calculus is that, if individuals and institutions that Beijing views as “stumbling blocks” to EU-China relations maintaining their “correct” direction are silenced or alienated, the strategic trajectory favorable to China will have a better chance of prevailing despite growing calls for a reevaluation of China policy across Europe.

Read more

- Sina Finance [CN]: Biden participated in the EU summit and the EU reaffirmed its strategic independence. Can US-EU relations go back to the past? (Quotes 1,2)

- Xinmin Evening News [CN]: Ding Chun: At war, is the EU still our strategic partner? (Quote 3)

- CIIS [CN]: The EU's "strategic autonomy" must not find the wrong direction (Quote 4)

- Sohu [CN]: Zhang Jian: EU's Strategic Independence and China-EU Relations in the Post-epidemic Era (Quote 5)

- CASS [CN]: "Independent cooperation" is the way for China-Germany and China-EU relations to be stable and far-reaching (Quote 6)

EU-China cooperation on climate is tested by economic competition and different commitment levels

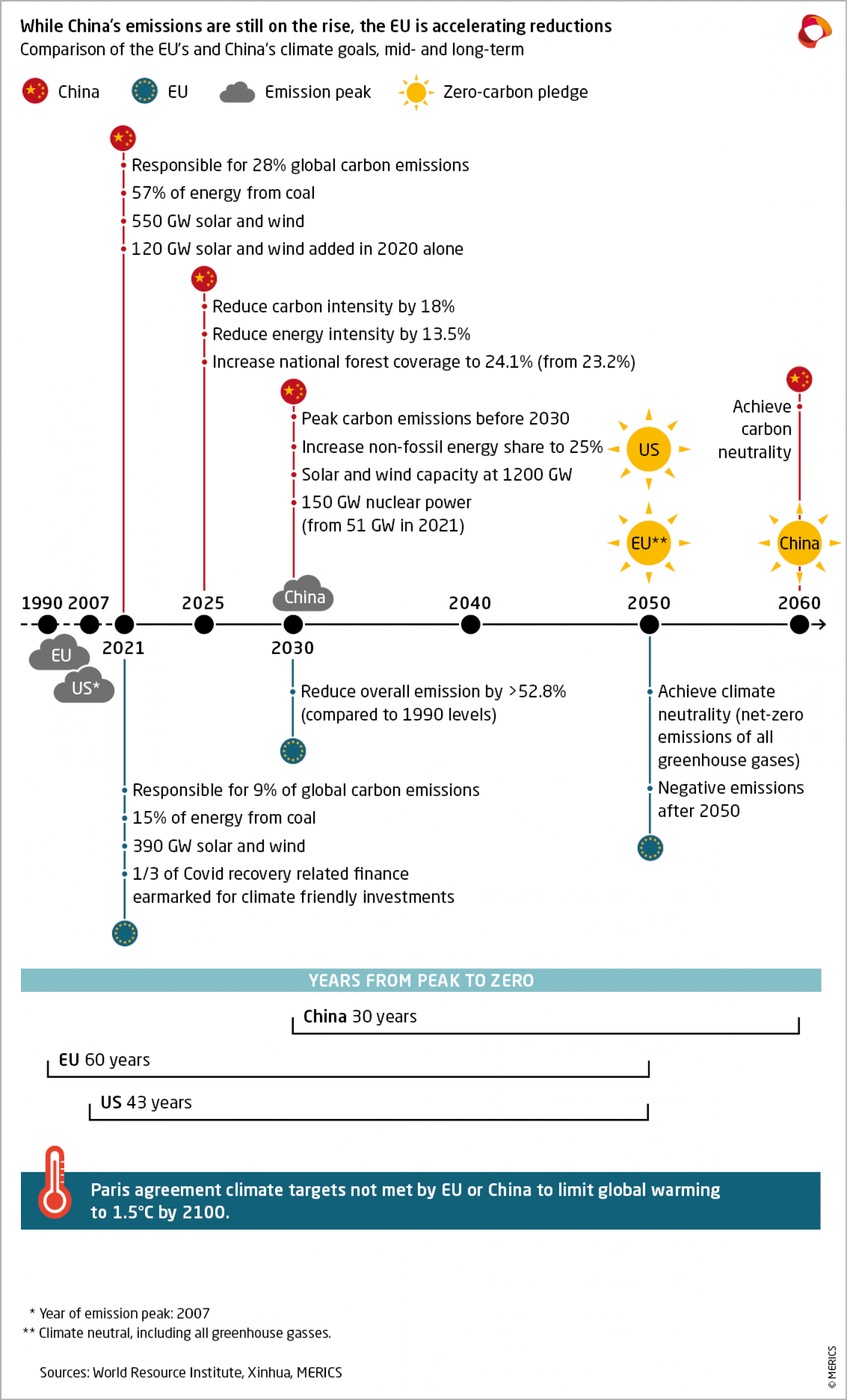

Emanuel Macron, Angela Merkel and Xi Jinping held a videoconference on April 16 to discuss climate cooperation and other topics. Both Merkel and Macron welcomed China’s pledge to reach carbon neutrality by 2060 but demanded more forceful climate action. Xi promised to “strengthen cooperation on climate change” but insisted on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities to address global warming, and warned against a European carbon border tax.

While the meeting took place the US and China’s special climate envoys, John Kerry and Xie Zhenhua, met in Shanghai to discuss Sino-American climate cooperation.

Following these meetings, the EU Climate Law was passed on April 21 and the “virtual climate summit” was hosted by US President Biden on April 22-23. China did not make any new climate pledges during that summit.

MERICS take: Amid tensions over trade, technology and values, it is hoped that climate policy will remain an anchor for constructive international cooperation. However, disagreement exists over the premises of cooperation, how responsibilities are distributed and, not least, competition and market access.

Xi has repeatedly emphasized China’s efforts to reduce emissions and shift to a low-carbon economy. However, China is the world’s largest CO2 emitter and emissions are set to continue rising until “before 2030”. Also, the 14th Five-year plan, issued in March, was unambitious on climate action, setting long-term objectives rather than strict short-term measures. On the other hand, China continues to push the development of strategic energy and green tech with industrial policies and targeted state support.

The EU’s Climate Law, meanwhile, consists not only of emission reduction targets but also advances economy-wide climate action aimed at reducing emissions.

As a latecomer to climate action, China is still battling poverty while simultaneously trying to leapfrog into a low-carbon economy. This leads to European companies facing growing competition in China over green technology, where local companies have a home advantage. Successful climate cooperation will depend on defining clear lines for competition and market access in green tech and energy industries that both sides can accept.

What to watch: The conflict lies in China’s plan for a long-term transition towards low-carbon economy, and the required short-term action needed to limit global warming at 1.5 °C, as ratified in the Paris Agreement. Neither side is currently on track to meet this target, but China is the taillight on climate action. The EU’s new Climate Law, setting EU emissions 52.8 percent lower by 2030 compared to 1990, and Biden’s pledge to reduce emissions by 52 percent compared to 2005, put the two blocs further ahead of China. The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, which is currently being mulled over, will be a litmus tests for the balance between cooperation and competition on climate.

Read more:

- E3G: Snapshot: the geopolitical context for global climate action

- Politico: China’s Xi slams EU carbon border levy plans

- ECFR: Climate superpowers: How the EU and China can compete and cooperate for a green future

- Xinhua [CN]: Xi Jinping held a video summit with French and German leaders

- Federal Government of Germany: Chancellor Merkel speaks with the presidents of France and China, Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping

- Climate Action Tracker: EU

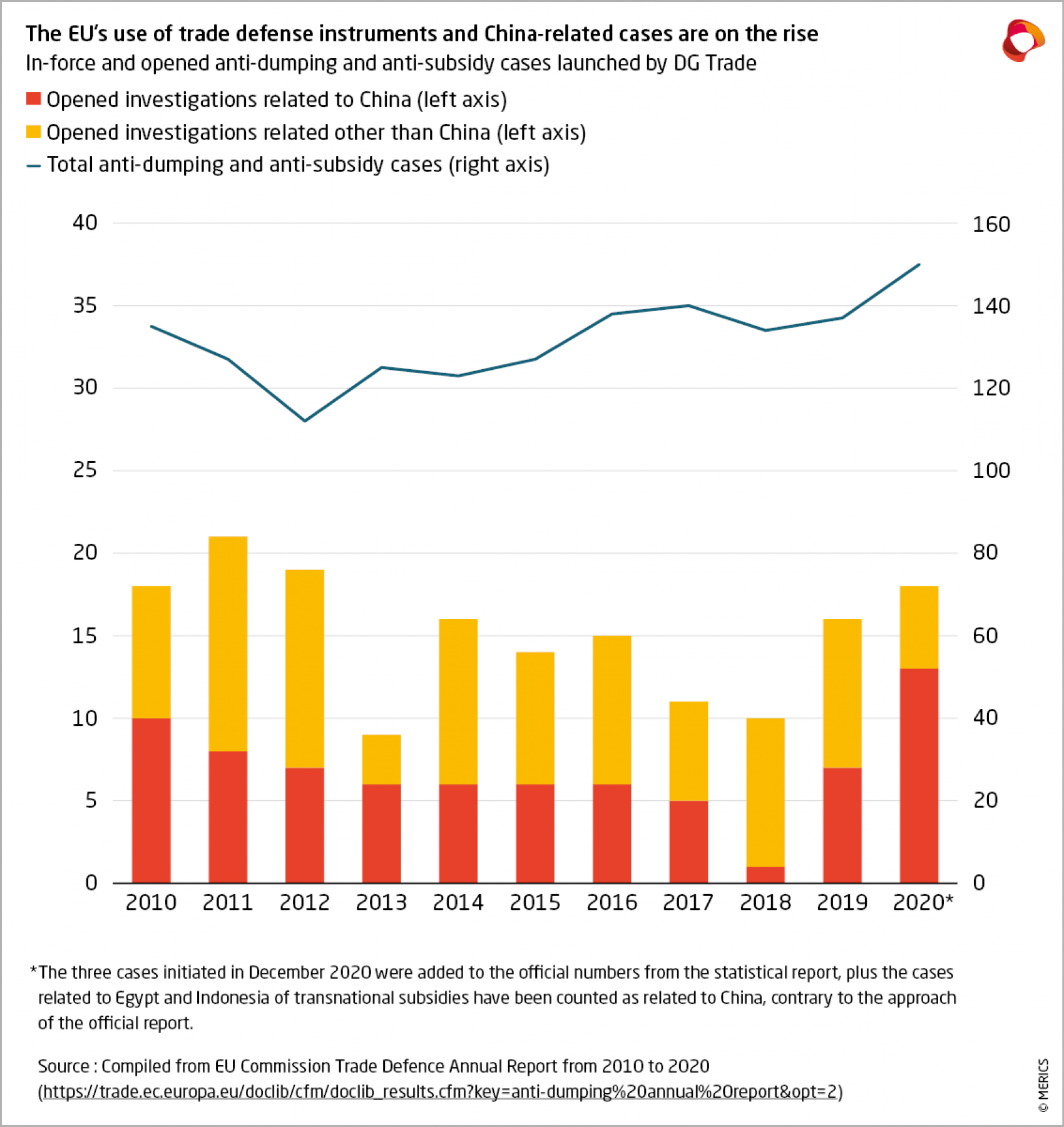

The EU targets distortions in the Chinese aluminum value chain

The Commission has imposed anti-dumping duties of 21 to 32 percent on “aluminum extrusions” imported from China, depending on the cooperativeness of Chinese producers. Used mostly in construction and transports, the imports amount to 800 million EUR in 2019. The decision follows initial findings that led to temporary tariffs being imposed in October 2020.

The penalties result from a detailed analysis of widespread distortions in the Chinese aluminum sector, which has led to the sector being categorized as not market-based. Instead of comparing export prices to domestic ones, the comparison was made with the normal price derived from a market-based sector with similar characteristics - in this case, the Turkish aluminum industry.

The list of distortions identified by the Commission includes state-sponsored credit through state-owned banks, state guarantees, wage cost distortion caused by lack of labor rights, state involvement in firms (including through Communist Party cells within private firms), and subsidized domestic inputs alongside constraints on exports. These are on top of more traditional distortions such as specific tax breaks and cash subsidies.

MERICS take: While the distortions identified largely derive from a document produced by the Commission in late 2017 and an OECD report on subsidies in the aluminum sector worldwide, the approach taken is innovative, bold and promising.

These distortions cover channels that were rarely touched upon in European trade defense instrument investigations prior to late 2019. They affect a large number of sectors in China and are highly contested by the Chinese authorities. Since the nomination of the first EU Chief Trade Enforcement Officer (CTEO) in August 2020, the Commission has initiated six anti-dumping cases on Chinese products, all touching on “new” channels for distortion, as well as three anti-subsidy cases, which is equivalent to the number of cases initiated for all partners in 2017 and in 2018.

The current EU Commission’s ambition is to take a more assertive stance towards foreign distortions. This trend can be seen as evidence that its ambition is beginning to materialize. Proposals for a legislation to tackle foreign subsidies in the competition policy and an instrument on public procurements are expected before year end.

What to watch: A formal reaction by China is still pending. According to the European Commission’s final report, it received comments from the Chinese government claiming the procedure breaches WTO rules. The claims were rebuffed by the Commission, which now seems set on using this approach on Chinese products in coming months. Given that this is part of an interim WTO-related dispute settlement mechanism – in place while the official one is still blocked by the United States – China could act on its comments and initiate a formal WTO case on the EU’s new practice.

Read more

- European Commission: Commission imposes anti-dumping duties on imports of aluminium extrusions from China

- OECD (2019): Measuring distortions in international markets: the aluminium value chain

- European Commission: Trade Defence Statistics covering 2020

- Euractiv : Commission outlines ‘greener’ and more assertive trade policy

- European Commission : Commission staff working document on significant distortions in the economy of the People's Republic of China for the purposes of trade defence investigations

Mario Draghi’s nascent China policy puts economic security and European coordination first

Four years after then Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni joined his French and German counterparts in advocating for the now operational EU-wide investment screening mechanism, Mario Draghi’s government is quietly putting Italy back in the front seat of intra-EU China policy coordination.

First, the Italian government reportedly considered views from the European Commission, Sweden and the Netherlands when, on March 31, it vetoed the acquisition of Milan-based semiconductor firm LPE. The prospective acquirer was Shenzhen Investment Holdings, a state-owned Chinese investor, and the takeover was blocked on national security grounds.

Later came the news, confirmed by Bloomberg and citing unnamed government officials, that the Italian and French economy ministers had acted in coordination to prevent the sale of a unit of Iveco SPA, a crown jewel in transport vehicle manufacturing, to China’s FAW Group. On Draghi’s behalf, Italy’s Economic Development Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti persuaded the companies to drop the talks, a decision announced by Iveco’s parent company CNH Industrial on April 17. His French counterpart Bruno Le Maire welcomed the news on Twitter, stressing Europe’s “industrial sovereignty”.

MERICS take: A little over two months since Draghi took office, the contours of his China policy are already taking shape. That the former European Central Bank chief only briefly touched on China in his inauguration speech (in the context of regional security tensions in Asia) was rather predictable; the previous coalition government had already distanced itself from the strategic naivety that had characterized Giuseppe Conte’s first cabinet, which had overseen Italy’s formal endorsement of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2019.

Given Draghi’s strong pro-European orientation, as well as his traditional pragmatism, it comes as no surprise that his approach to bilateral economic relations with China prioritizes careful consideration of national and European interests, against which commercial opportunities must be weighed. Amid a devastating pandemic-induced economic crisis, Rome has acted swiftly to protect strategic industrial assets from foreign takeovers – apparently also by making use of the novel cooperation mechanism under the EU investment screening Regulation for the LPE deal.

Iveco’s case is even more interesting. The existing instruments do not apply to this sector, so the government instead used political channels to discourage the deal. This was done in coordination with Paris and based on an industrial policy calculus, as Italy prepares to receive about 200 billion EUR of European recovery funds that could be used to support crisis-hit industries.

What to watch: Draghi’s China policy will likely continue to be marked by pragmatism and an emphasis on European coordination, as well as coordination with allies and partners beyond Europe. It is within such a framework that economic cooperation with China will be pursued. We should expect Italy’s new government to welcome concrete opportunities – FAW has just launched a joint venture to design and manufacture new energy vehicles in Emilia Romagna – while keeping security and strategic risks in check. Rome is now mulling over expanding its investment screening powers to cover the automotive and steel sectors, both strategic for Italy’s economy. As for political relations with China, Draghi is yet to fully show his hand. The ongoing debate in the parliament’s lower house about Italy’s stance on human rights abuses in Xinjiang will be an important test.

Read more

- Bloomberg: CNH Ends Talks with China’s FAW on Sale of Iveco Unit

- Bloomberg: Draghi Shuns Chinese Cash with European Recovery Funds Coming

- MERICS EU-China Weekly Review: Mario Draghi’s government deploys “Golden Power Law” against Chinese companies

- Corriere della Sera [IT]: Draghi ferma i cinesi con il «golden power»: cos’è e perché l’italiana Lpe è stata protetta

- Formiche [IT]: Iveco-Faw, si può mettere il golden power? Dubbi e scenari